Key Findings

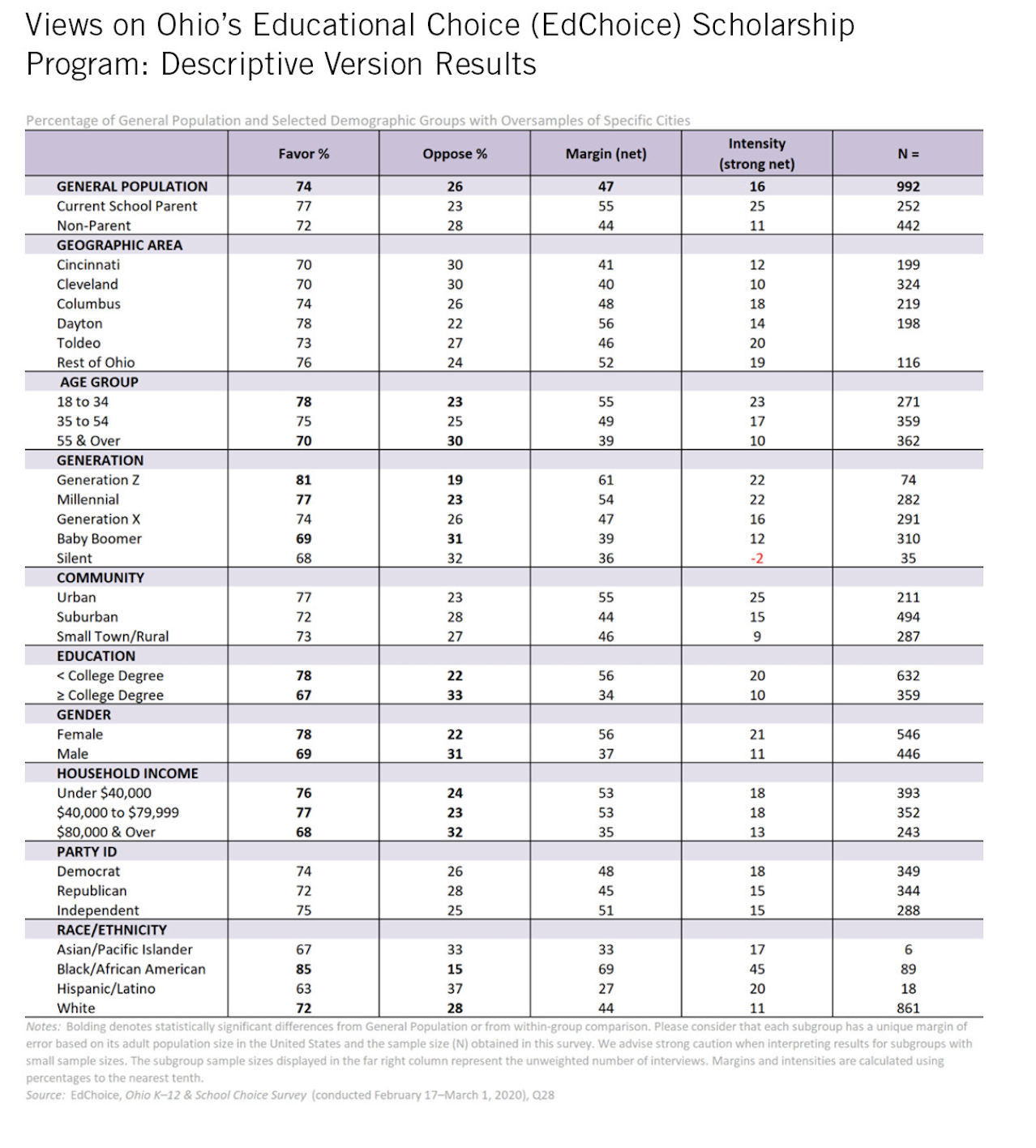

- Two-fifths of Ohioans (40%) said they had never heard of Ohio’s Educational Choice Scholarship Program. When asked about opinions without offering any descriptions, 43 percent are in favor of the program. When provided with a definition of the program, nearly three-fourths of Ohioans (74%) are in favor of the state’s largest publicly funded scholarship (voucher) program.

- Ohio African Americans (85%) were the observed demographic group most likely to favor the Educational Choice Scholarship Program, while Ohioans with a college degree (67%) were the least likely to favor the program.

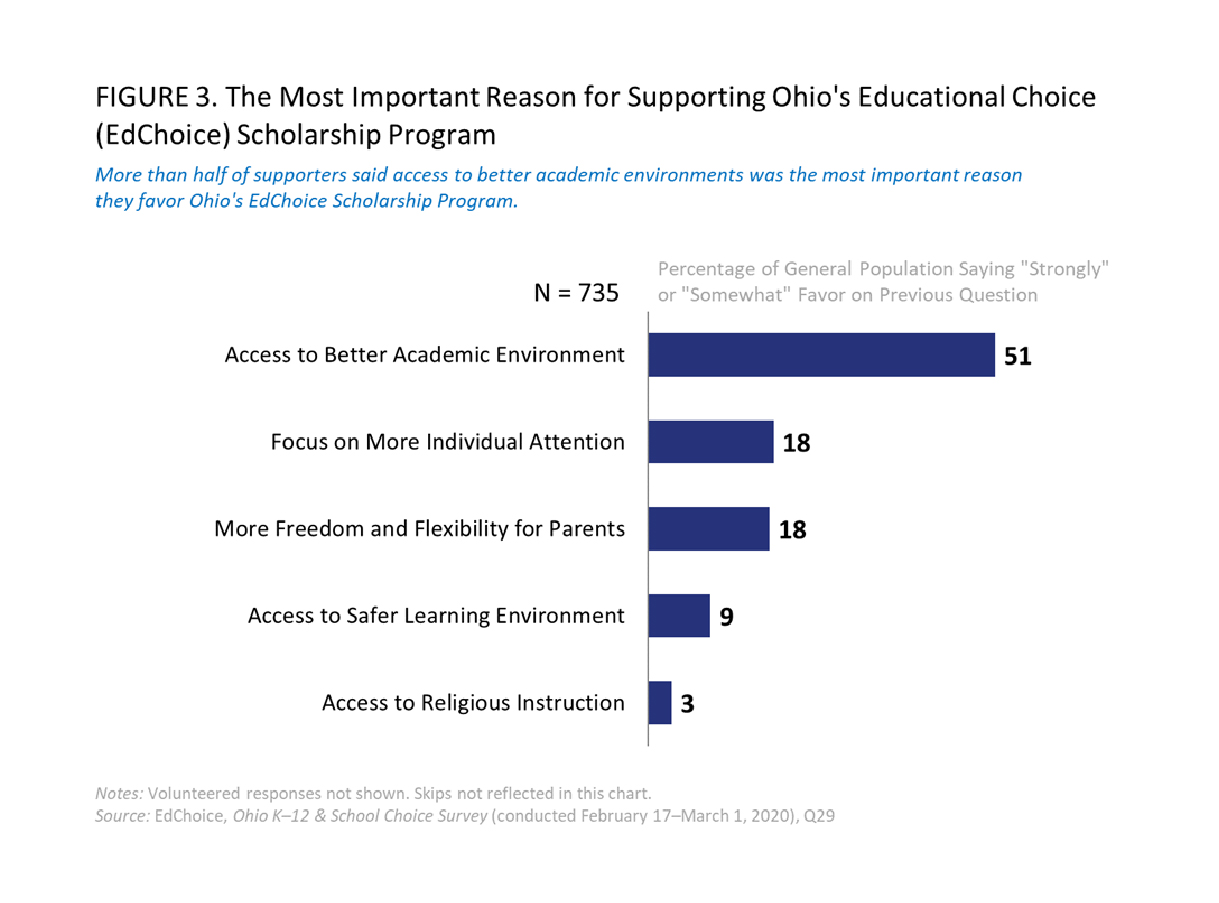

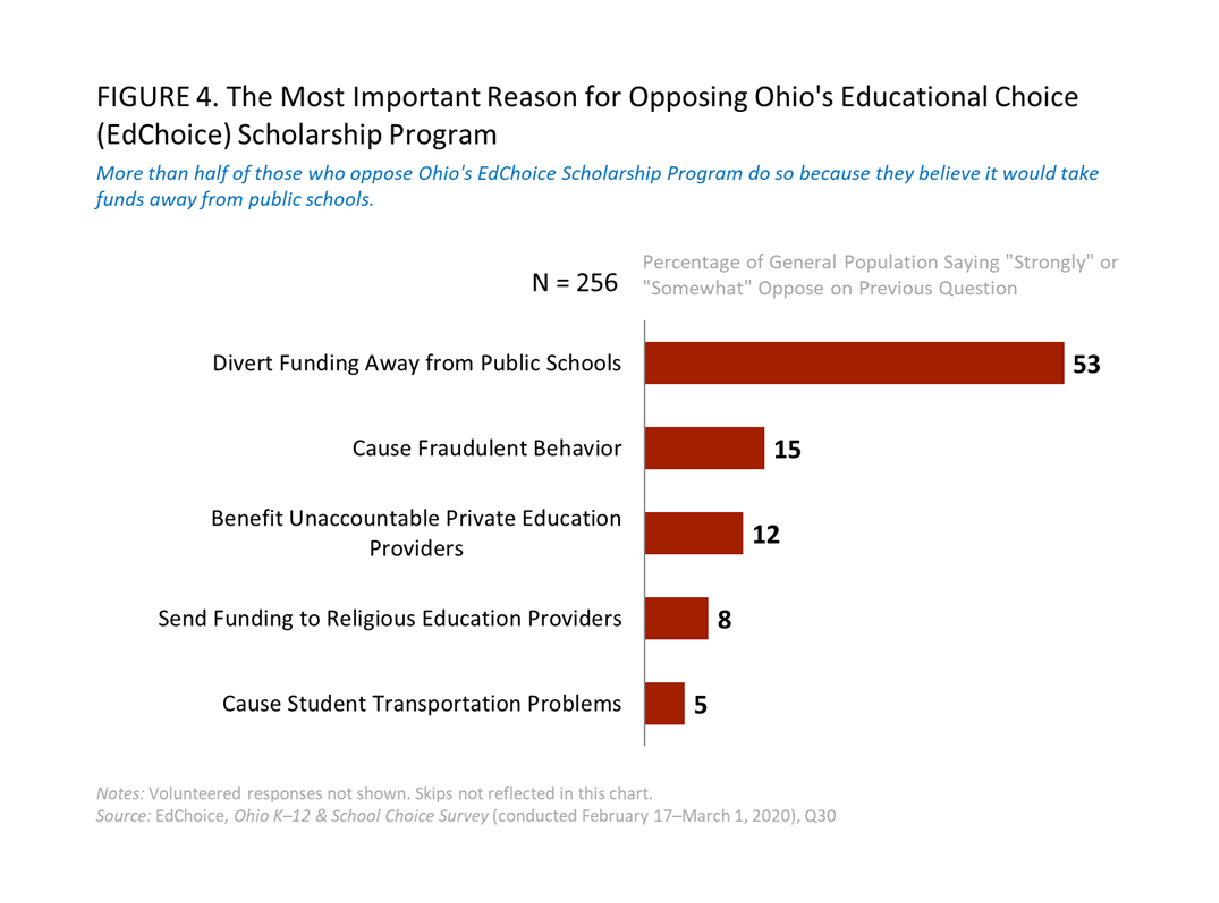

- More than half of those favoring the Educational Choice Scholarship Program (51%) said their most important reason for doing so was access to better academic environments. More than half of those opposing the program said their most important reason for doing so was their belief that the program would divert funding away from public schools; however, research shows that the program has resulted in cumulative savings of $429,228,122 from inception through 2014–15.1

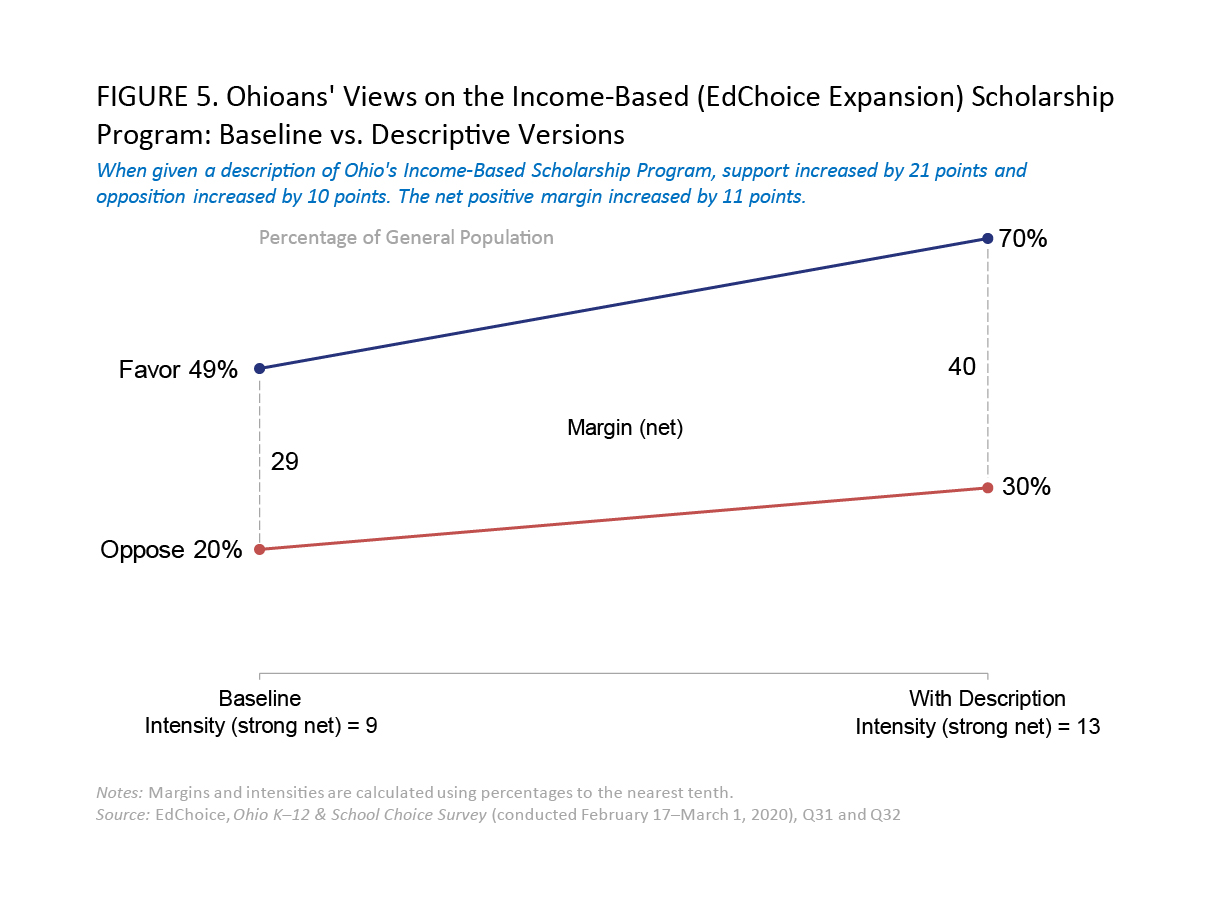

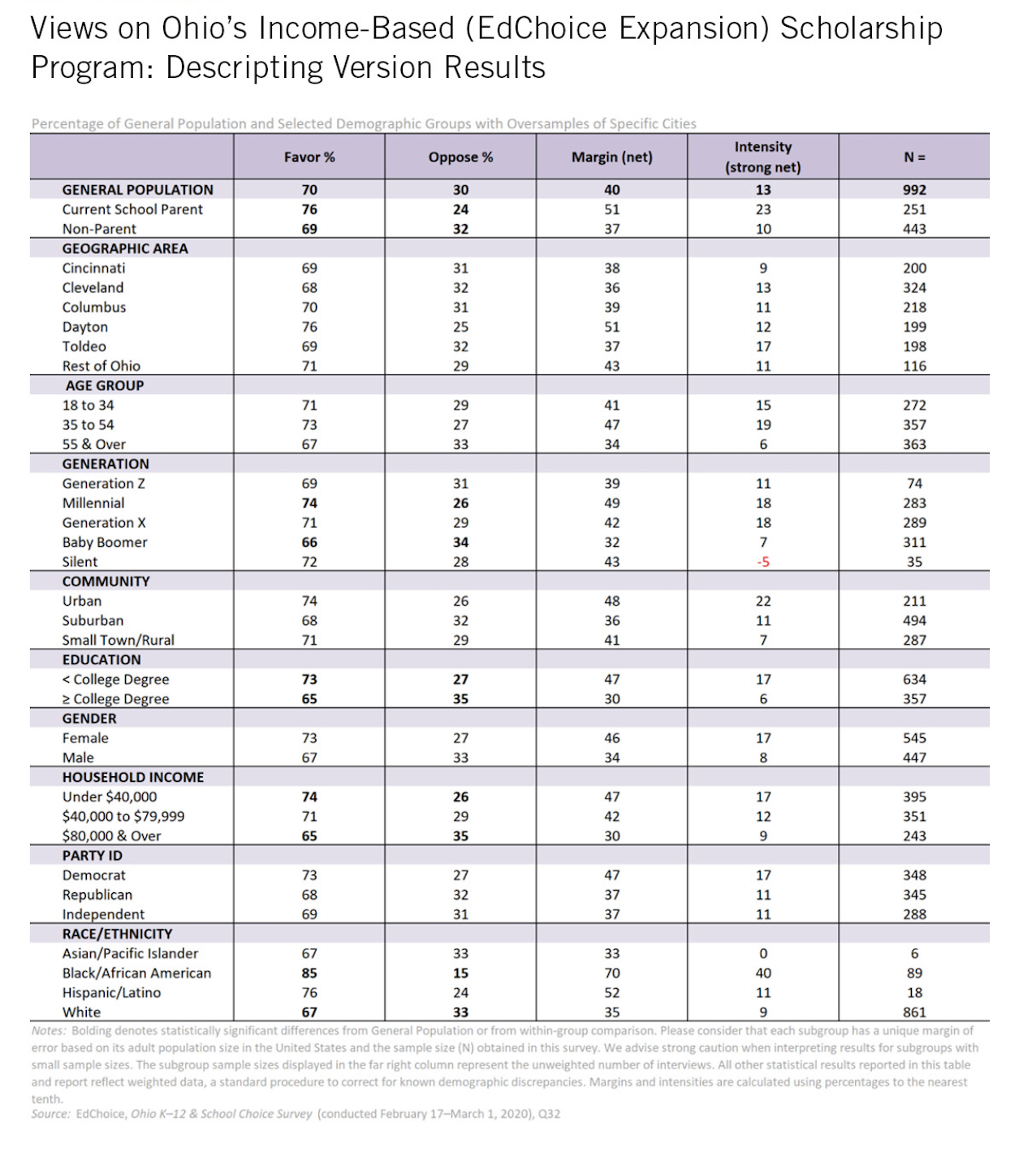

- Nearly one-third of Ohioans (31%) said they had never heard of Ohio’s Income-Based Scholarship Program. When asked about opinions without offering any descriptions, 49 percent are in favor of the program. When provided with a definition of the program, more than two-thirds of Ohioans (70%) are in favor of the program.

- Ohio African Americans (85%) were the observed demographic most likely to favor the Income-Based Scholarship Program, while Ohioans with a college degree (65%) and high-income earners (65%) were the least likely to favor the program.

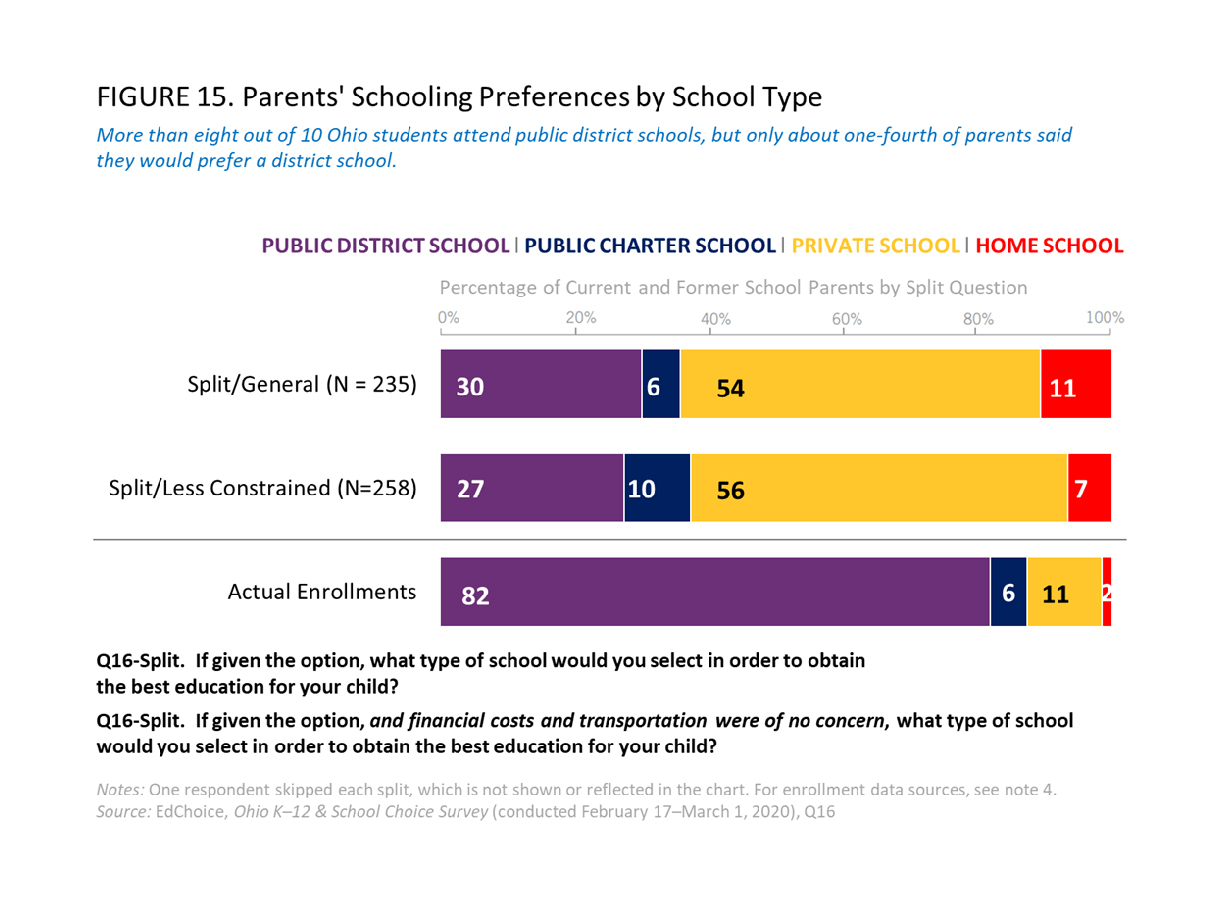

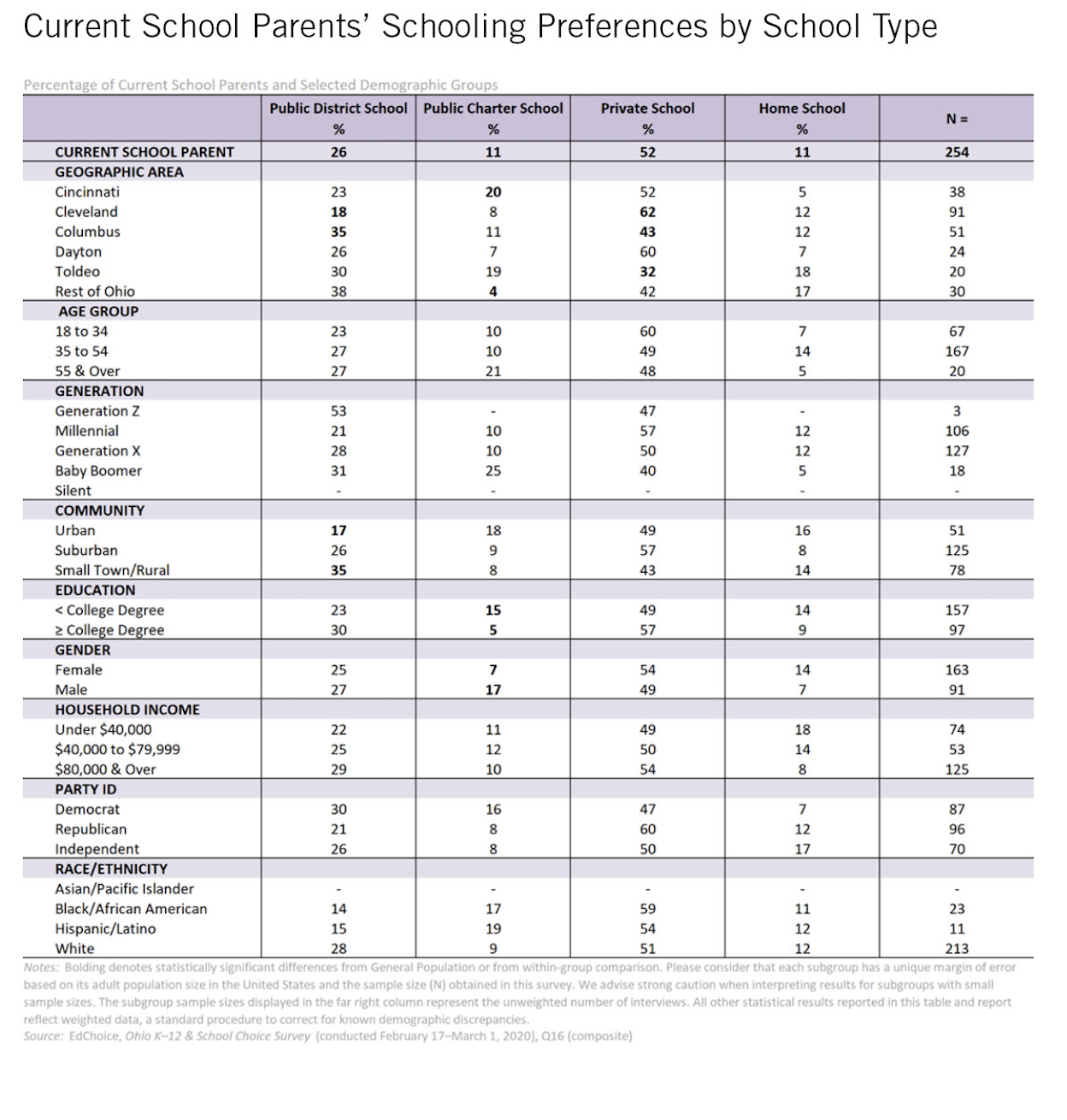

- More than half of Ohio current school parents (52%) said they would prefer to send their children to private school, whereas only 11 percent of Ohio K–12 students are enrolled in a private school. Eighty-two percent of Ohio’s K–12 students attend a regular public school, but 26 percent of parents said they would select this type of school for their child if given the option.

- In a split-sample experiment, 56 percent of Ohio current and former school parents said that if financial cost and transportation were of no concern, they would select private schooling to obtain the best education for their child.

- Ohioans severely underestimate how much is spent per student in public schools. Half of respondents offering an answer said Ohio spends $3,500 or less per student, which is less than one-third of reported 2016–17 spending ($12,649).2 In total, 95 percent of respondents underestimated per-pupil public spending.

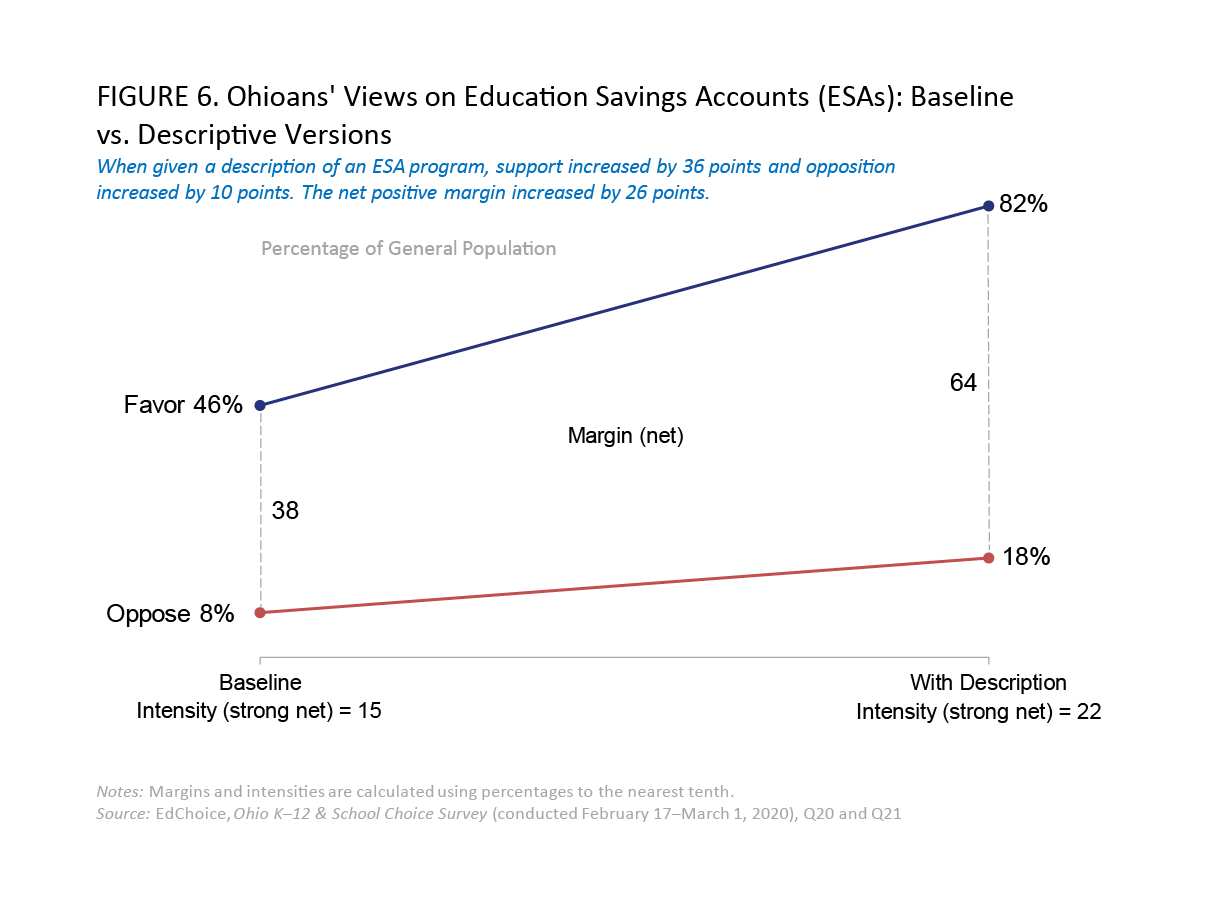

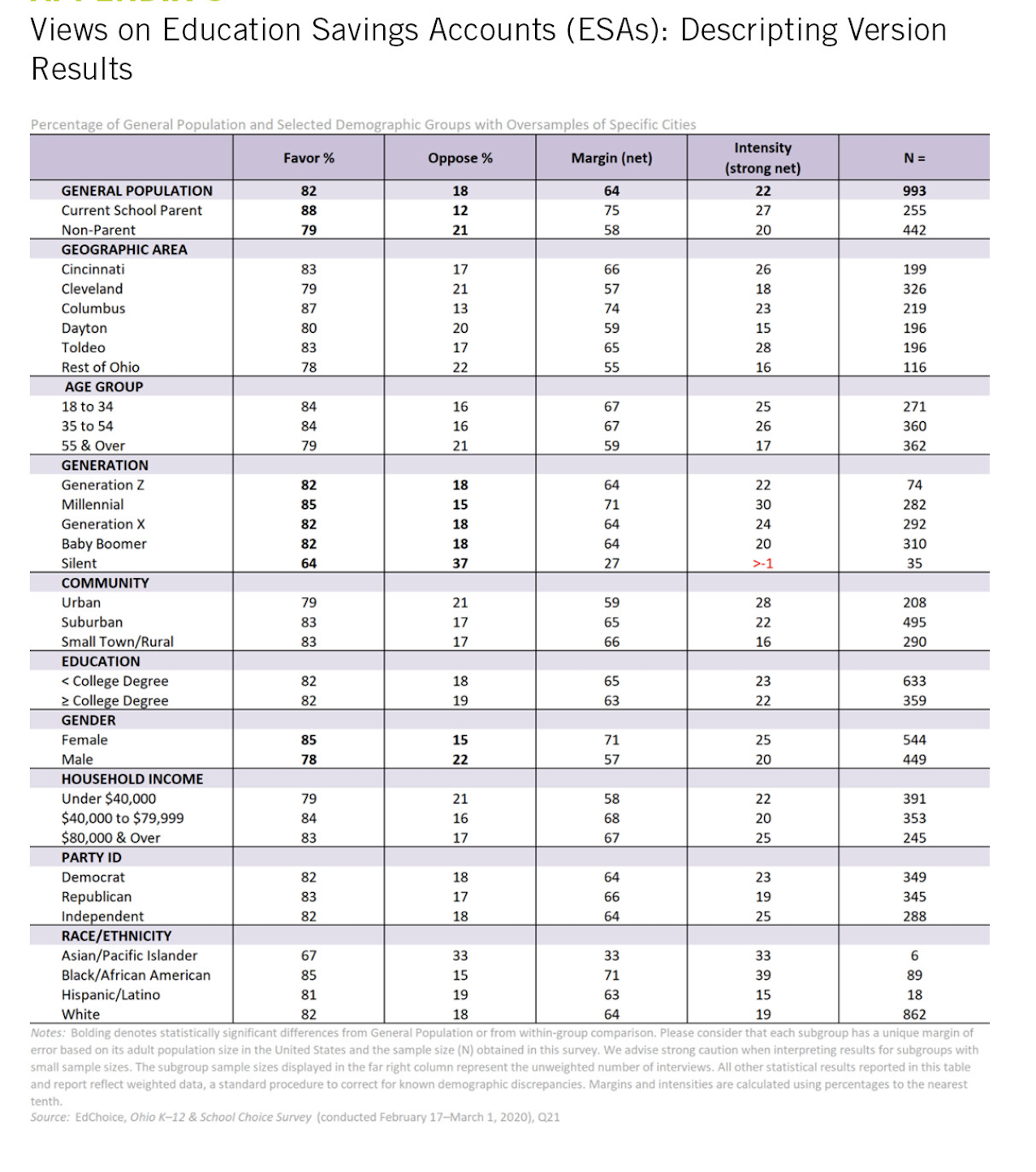

- Nearly half of Ohioans (46%) had never heard of Education Savings Accounts (ESAs). However, after being provided with a definition, 82 percent of Ohioans are in favor of ESAs.

Overview

Ohio has one of the oldest private school choice programs in the nation and the nation’s only private school choice program designed solely for students with autism.

Ohio’s Cleveland Scholarship Program began in 1996 and is open to families in the Cleveland Metropolitan School District, with priority given to low-income families. As of Fall 2019, there were 7,251 students receiving publicly funded scholarships (vouchers) to attend private schools, with the most recent average amount being $4,863 (2017–18). Notably, the U.S. Supreme Court deemed the Cleveland Scholarship Program constitutional in 2002. Ohio’s Autism Scholarship Program began in 2004. As of last school year (2018–19), there were 3,789 students receiving vouchers for education services from private providers, including tuition at private schools, with the most recent average amount being $22,996 (2017–18). Ohio’s Educational Choice (EdChoice) Scholarship Program began in 2006 and is open to students who would otherwise attend a low-performing public school. As of Fall 2019, there were 28,197 students receiving vouchers to attend private schools, with the most recent average amount being $4,762 (2017– 18). Ohio’s Jon Peterson Special Needs Scholarship Program began in 2012 and is open to students with special needs. As of last school year (2018–19), there were 6,373 students receiving vouchers to pay for private school tuition and additional services covered by their Individualized Education Plans, with the most recent average amount being $9,913 (2017–18). Ohio’s Income-Based Scholarship Program launched in 2013 and is open to income-eligible students in grades K–6. As of Fall 2019, there were 11,353 students receiving vouchers to attend private schools, with the most recent average amount being $4,097 (2017–18). In total, there are approximately 57,000 students receiving a voucher in Ohio.3

The purpose of the Ohio K–12 & School Choice Survey is to measure public opinion on, and in some cases awareness or knowledge of, a range of K–12 education topics and school choice reforms. EdChoice and School Choice Ohio developed this project in partnership with Braun Research, Inc., which conducted the online interviews, collected the survey data, and provided data quality control. EdChoice is a national nonprofit organization that works on K–12 policy and research; it does not oversee or administer any state-based educational choice programs, including the EdChoice Scholarship in Ohio.

We explore the following topics and questions:

- In which direction do Ohioans think K–12 education in the state is heading?

- Do they believe district schools are adequately funded?

- How would they rate the various types of schooling options in the state in general and in their area specifically?

- What sort of schooling options would they prefer for their own children?

- How supportive are Ohioans of the various types of educational choice programs?

- And what are their views on Ohio’s current educational choice programs?

Methods & Data

The Ohio K–12 & School Choice Survey project, funded and developed by EdChoice in partnership with School Choice Ohio and conducted by Braun Research, Inc., interviewed a statistically representative statewide sample of Ohio voters (age 18+). Data collection methods consisted of a non-probability-based optin online panel. The unweighted statewide sample includes a total of 1,265 online interviews completed in English from February 17–March 1, 2020. The margin of sampling error for the total statewide sample is ±2.75 percentage points.

The statewide sample was weighted using population parameters from the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2010 Decennial Census for voters living in the state of Ohio. Results were weighted on age, county, race, ethnicity, community type, income, and gender. Weighting based on county used data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2017 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates. We intended to also weight by party, but Ohio does not report party affiliations; one does not need to be registered with a party to vote in the primary.

Ground Rules

Before discussing the survey results, we want to provide some brief ground rules for reporting statewide sample and demographic subgroup responses in this brief. For each survey topic, there is a sequence for describing various analytical frames. We note the raw response levels for the statewide sample on a given question. Then we consider the statewide sample’s margin, noting differences between positive and negative responses. If we detect statistical significance on a given item, then we briefly report demographic results and differences. We do not infer causality with any of the observations in this brief. Aside from the demographic tables in the appendices, we do not use specific subgroup findings if there were fewer than 80 respondents.

Explicit subgroup comparisons/differences are statistically significant with 95 percent confidence, unless otherwise clarified in the narrative. We orient any listing of subgroups’ margins around more/less “likely” to respond one way or the other, usually emphasizing the propensity to be more/less positive. Subgroup comparisons are meant to be suggestive for further exploration and research beyond this project.

Findings

PUBLICLY FUNDED SCHOLARSHIPS (VOUCHERS)

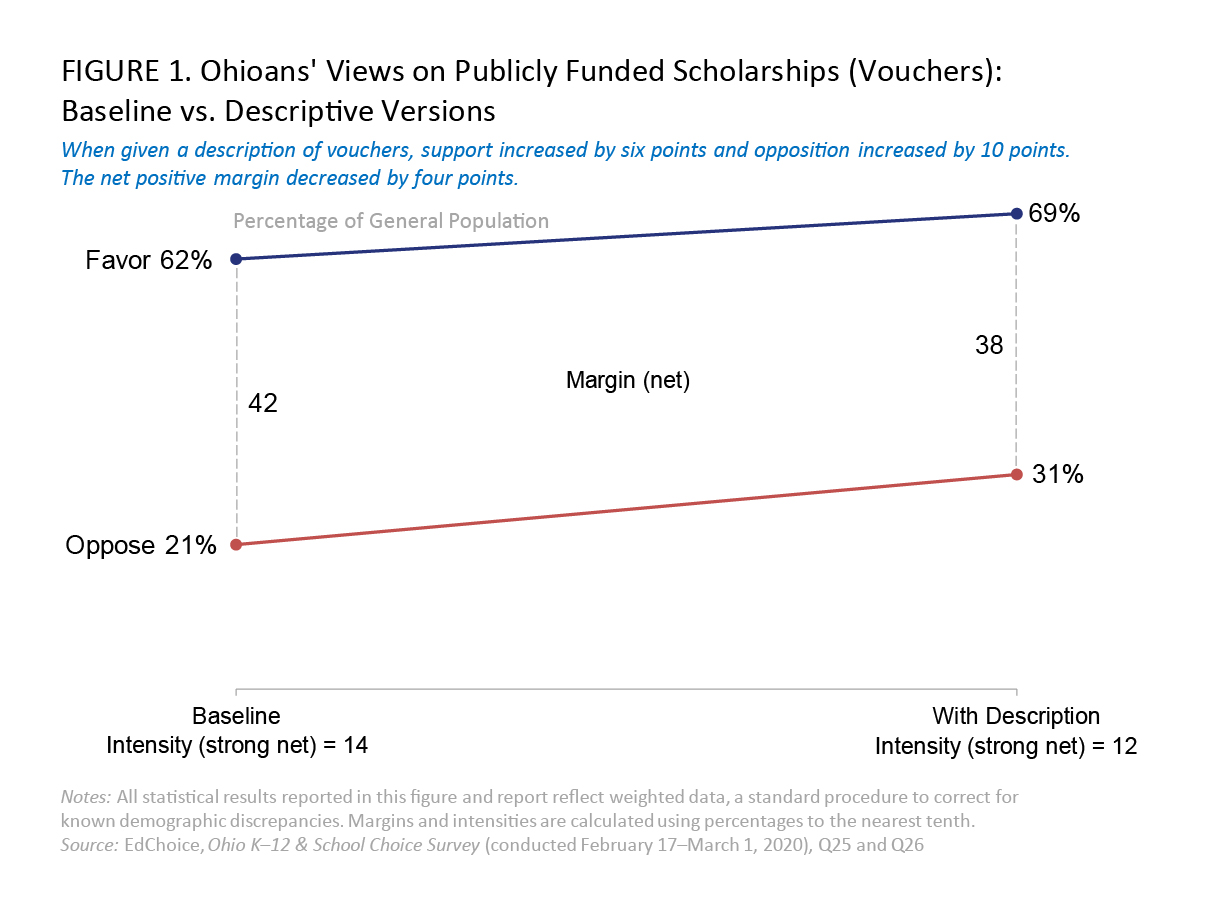

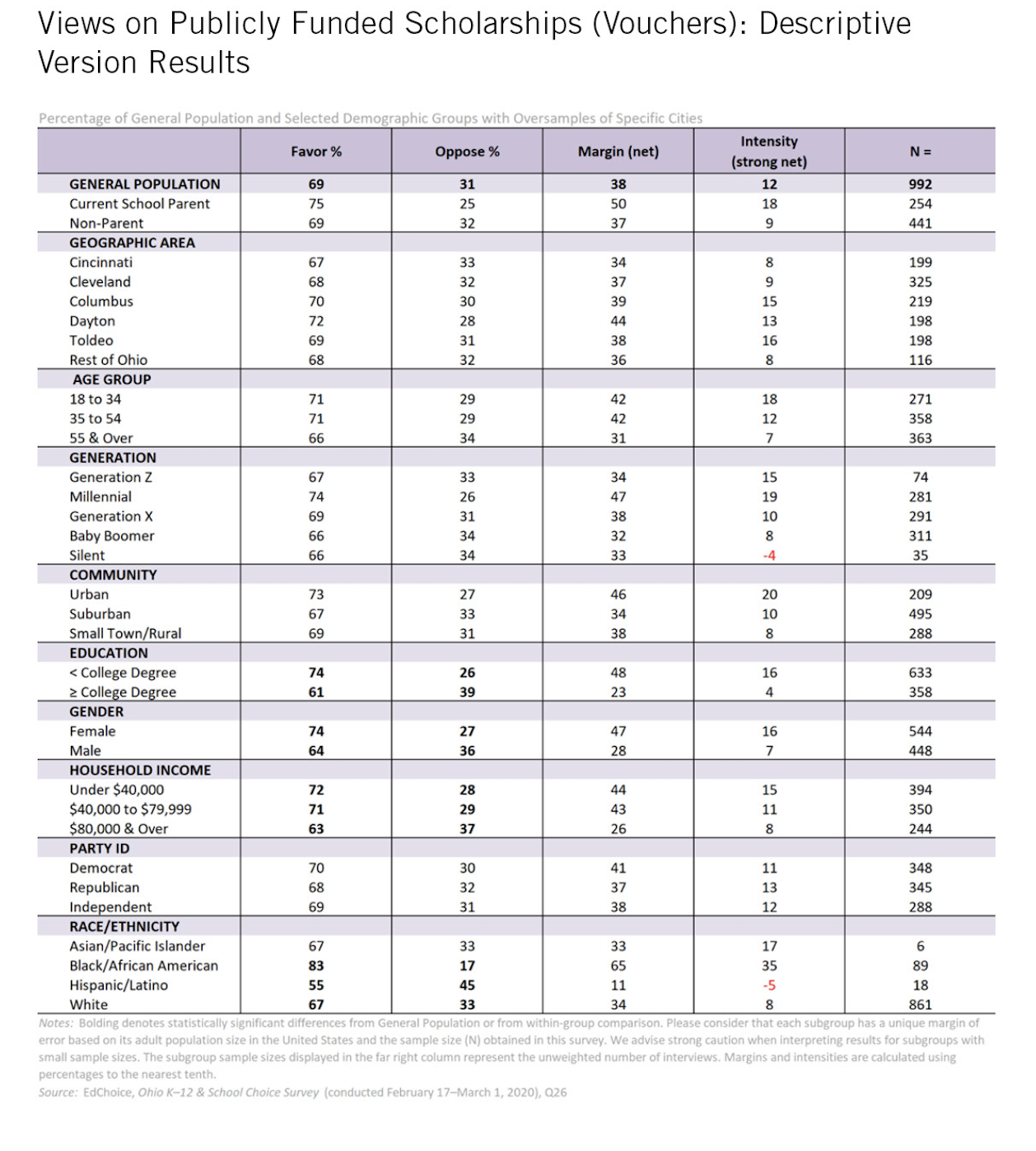

Ohioans are more than twice as likely to favor publicly funded scholarships, or vouchers, than they are to oppose them. More than two-thirds of respondents (69%) said they supported vouchers after being given a description, whereas 31 percent said they oppose. The margin is +38 percentage points. Ohioans are more likely to express an intensely positive response compared with a negative response (23% “strongly favor” vs. 12% “strongly oppose”).

An initial voucher question inquired about an opinion without offering any description. On this baseline question, 62 percent of respondents said they favored vouchers, and 21 percent said they opposed them. In the follow-up question, respondents were given a general description of a voucher program. With this information, support increased six points to 69 percent, and opposition increased 10 points to 31 percent.

One-sixth of Ohioans (17%) said they had never heard of vouchers on the baseline item. The subgroups having the highest proportions saying they had never heard of vouchers are: low-income earners (21%) and small town and rural residents (24%).4

The margins of all subgroups observed are positive— and they all exceed +11 percentage points. The largest positive margins are among: African Americans (+45 points), current school parents (+50 points), those without a college degree (+48 points), Millennials (+47 points), and females (+47 points). The subgroups exhibiting the lowest net positive margins for voucher favorability include college graduates (+23 points), high-income earners (+26 points), and males (+28 points).

In addition:

- Females (74%) were more likely to favor vouchers than males (64%).

- Low-income earners (72%) and middle-income earners (71%) were more likely to favor vouchers than high-income earners (63%).

- Those without a college degree (74%) were more likely to favor vouchers than college graduates (61%).

- African American Ohioans (83%) were more likely to favor vouchers than white Ohioans (67%).

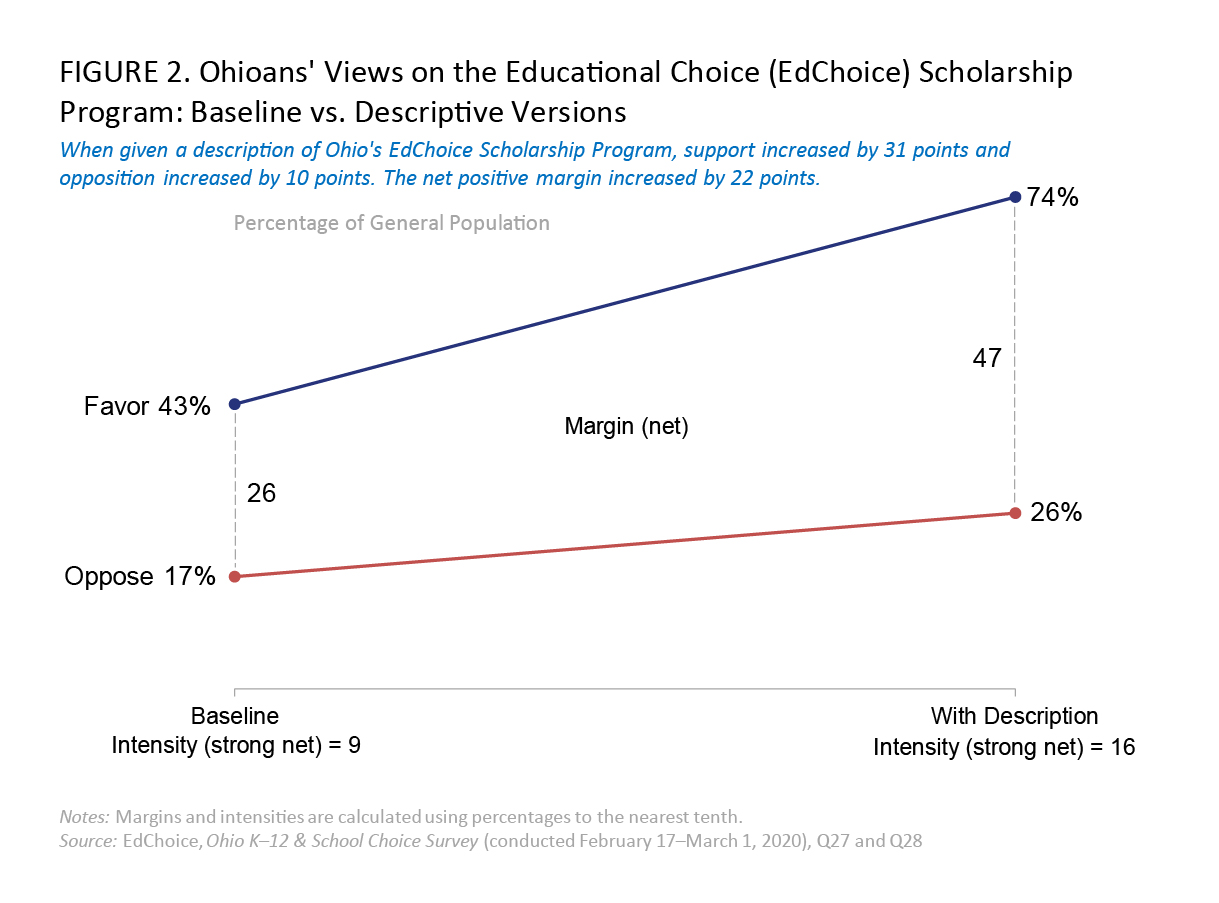

Educational Choice (EdChoice) Scholarship Program Ohioans broadly support the Educational Choice Scholarship Program, cutting across all observed demographics. Nearly three-fourths of respondents (74%) said they supported Ohio’s largest voucher program, whereas 26 percent said they oppose. The margin is +47 percentage points. Ohioans are more likely to express an intensely positive response compared with a negative response (25% “strongly favor” vs. 9% “strongly oppose”).

An initial Educational Choice Scholarship Program question inquired about an opinion without offering any description. On this baseline question, 43 percent of respondents said they favored EdChoice Scholarships, and 17 percent said they opposed them. In the follow-up question, respondents were given a description of Ohio’s Educational Choice Scholarship Program. With this program description, support increased 31 points to 74 percent, and opposition increased 10 points to 26 percent.

Two-fifths of Ohioans (40%) said they had never heard of Ohio’s Educational Choice Scholarship Program on the baseline item. The subgroups having the highest proportions saying they had never heard of Ohio’s Educational Choice Scholarship Program are: seniors (44%), Baby Boomers (44%), low-income earners (44%), females (44%), small town and rural residents (45%), Dayton residents (48%), and former school parents (50%).

The margins of all subgroups observed are positive— and they all exceed +27 percentage points. The largest positive margins are among: African Americans (+69 points), Generation Z (+61 points), females (+56 points), those without a college degree (+56 points), and Dayton residents (+56 points). The subgroups exhibiting the lowest net positive margins for EdChoice Scholarship favorability include college graduates (+34 points), high-income earners (+35 points), and males (+37 points).

In addition:

- Younger Ohioans (78%) were more likely to favor the Educational Choice Scholarship Program than seniors (70%).

- Generation Z (81%) and Millennials (77%) were more likely to favor EdChoice Scholarships than Baby Boomers (69%).

- Those without a college degree (78%) were more likely to favor the program than college graduates (67%). Females (78%) were more likely to favor EdChoice Scholarships than males (69%).

- Low-income earners (76%) and middle-income earners (77%) were more likely to favor the voucher program than high-income earners (68%).

- African American Ohioans (85%) were more likely to favor the state’s Educational Choice Scholarship Program than white Ohioans (72%).

Of the current school parents who responded to the survey, 23 percent had never heard of the Educational Choice Scholarship Program and 34 percent had heard of the program did not apply. In a follow-up item, we learned the most common reasons for supporting EdChoice Scholarships are: “access to better academic environment” (51%), “focus on more individual attention” (18%), and “more freedom and flexibility for parents” (18%). Respondents opposed to EdChoice Scholarships answered a similar follow-up question. By far the most common reason for opposing this policy is the belief it would “divert funding away from public schools” (53%).

INCOME-BASED (EDCHOICE EXPANSION) SCHOLARSHIP PROGRAM

Ohioans are much more likely to favor Income-Based Scholarships than they are to oppose them. More than two-thirds of respondents (70%) said they supported Ohio’s income-based voucher program, whereas 30 percent said they oppose. The margin is +40 percentage points. Ohioans are more likely to express an intensely positive response compared with a negative response (21% “strongly favor” vs. 8% “strongly oppose”).

An initial Income-Based Scholarship Program question inquired about an opinion without offering any description. On this baseline question, 49 percent of respondents said they favored Income-Based Scholarships, and 20 percent said they opposed them. In the follow-up question, respondents were given a description of Ohio’s Income-Based Scholarship Program. With this program description, support increased 21 points to 70 percent, and opposition increased 10 points to 30 percent.

Nearly one-third of Ohioans (31%) said they had never heard of Ohio’s Income-Based Scholarship Program on the baseline item. The subgroups having the highest proportions saying they had never heard of Ohio’s Income-Based Scholarship Program are: Generation Z (35%), those without a college degree (35%), former school parents (35%), females (36%), and small town and rural residents (38%).

The margins of all subgroups observed are positive— and they all exceed +30 percentage points. The largest positive margins are among: African Americans (+70 points), current school parents (+51 points), Dayton residents (+51 points), and Millennials (+49 points). The subgroups exhibiting the lowest net positive margins for Income-Based Scholarship favorability include college graduates (+30 points), high-income earners (+30 points), Baby Boomers (+32 points), seniors (+34 points), and males (+34 points).

In addition:

- Current school parents (76%) were more likely to favor the Income-Based Scholarship Program than non-parents (69%).

- Millennials (74%) were more likely to favor Income-Based Scholarships than Baby Boomers (66%).

- Those without a college degree (73%) were more likely to favor the program than college graduates (65%).

- Females (78%) were more likely to favor Income Based Scholarships than males (69%).

- Low-income earners (74%) were more likely to favor the voucher program than high-income earners (65%).

- African American Ohioans (85%) were more likely to favor the state’s Income-Based Scholarship Program than white Ohioans (67%).

Of the current school parents who responded to the survey, 30 percent had never heard of Ohio’s Income Based Scholarship Program and 37 percent had heard of the program did not apply.

EDUCATION SAVINGS ACCOUNTS (ESAS)

Ohioans are more than four times as likely to support Education Savings Accounts (ESAs) than they are to oppose them. More than four-fifths of respondents (82%) said they supported ESAs, whereas 18 percent said they oppose. The margin is +64 percentage points. Ohioans are more likely to express an intensely positive response compared with a negative response (27% “strongly favor” vs. 5% “strongly oppose”).

An initial ESA question inquired about an opinion without offering any description. On this baseline question, 46 percent of respondents said they favored an ESA system, and 8 percent said they opposed them. In the next question, respondents were given a description of a general ESA program. With this program-specific information, support increased 36 points to 82 percent, and opposition increased 10 points to 18 percent.

Nearly half of Ohioans (46%) said they had never heard of ESAs on the baseline item. The subgroups having the highest proportions saying they had never heard of ESAs are: those without a college degree (50%), urbanites (50%), low-income earners (51%), small town and rural residents (51%), and Generation Z (55%).

The margins of all subgroups observed are positive— and they exceed +55 percentage points for all subgroups with more than 35 respondents. The largest positive margins are among current school parents (+75 points), Columbus residents (+74 points), females (+71 points), African Americans (+71 points), and Millennials (+71 points). The subgroups exhibiting the lowest net positive margins for ESA favorability include males (+57 points), Cleveland residents (+57 points), non-parents (+58 points), and low-income earners (+58 points).

In addition:

Current school parents (88%) were more likely to favor ESAs than non-parents (79%).

Females (85%) were more likely to favor ESAs than males (78%).

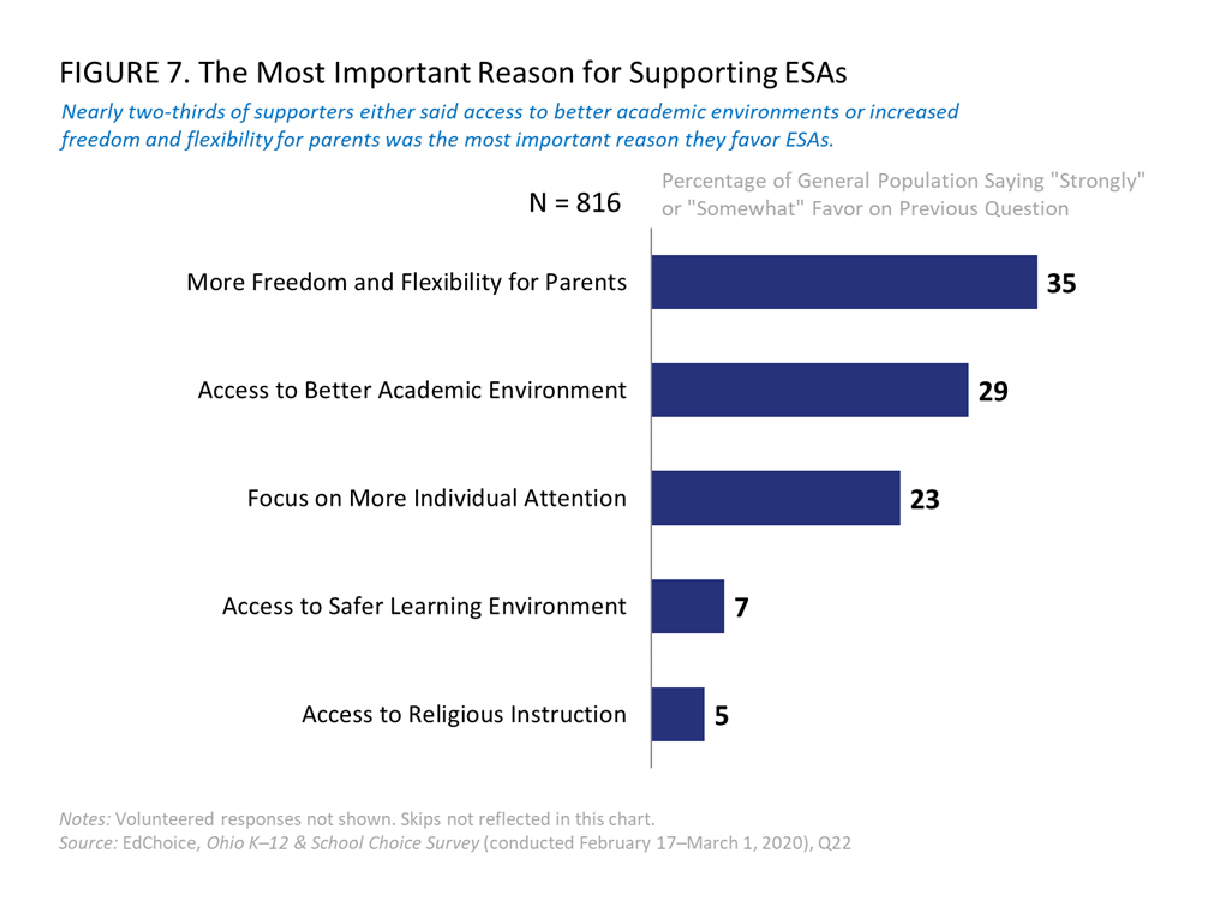

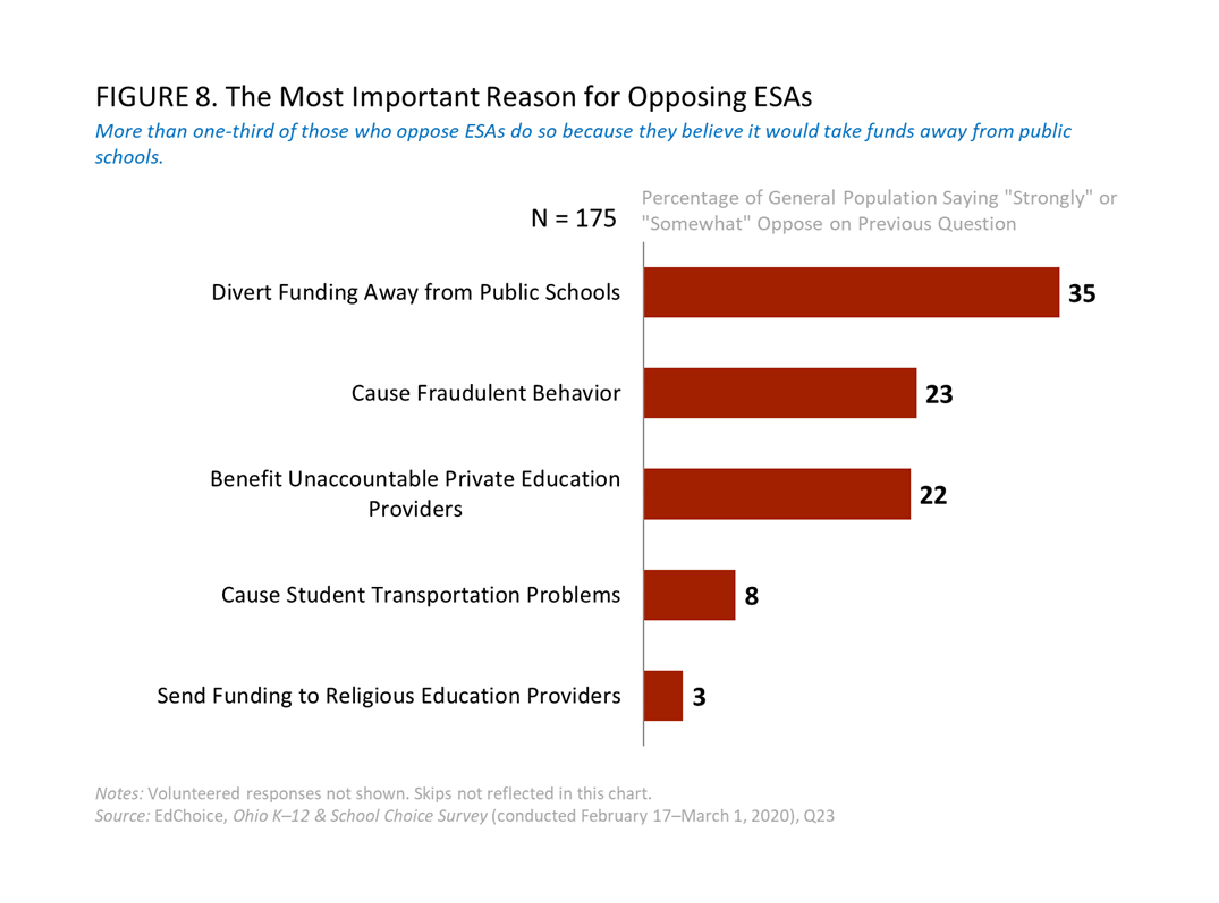

In a follow-up item, we learned the most common reasons for supporting ESAs are: “more freedom and flexibility for parents” (35%), “access to better academic environment” (29%), and “focus on more individual attention” (23%). Respondents opposed to ESAs answered a similar follow-up question. By far the most common reason for opposing this policy is the belief it would “divert funding away from public schools” (35%).

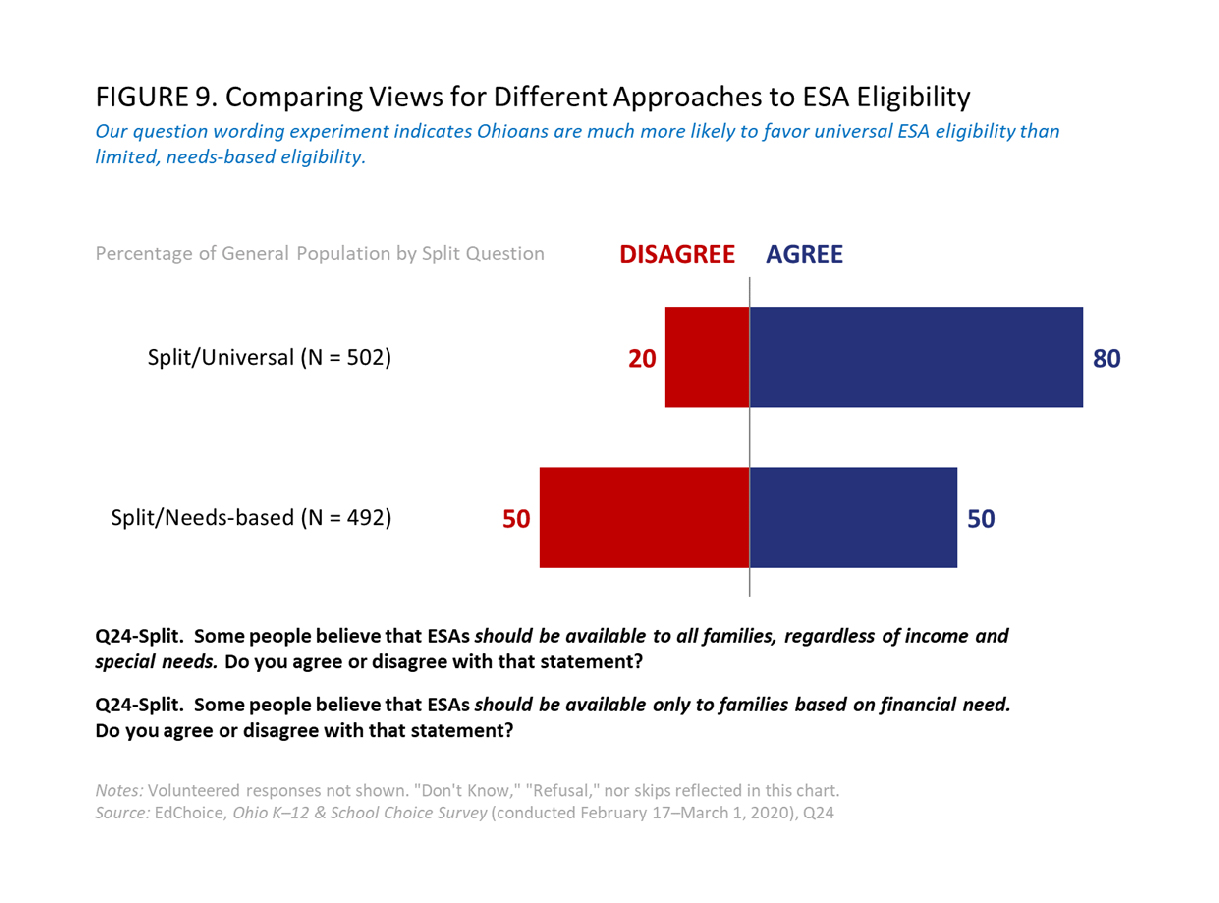

A subsequent split-sample experiment shows Ohioans are inclined toward universal eligibility for ESAs rather than means-tested eligibility based solely on financial need. In the universal split, 80 percent of respondents said they agree with the statement that “ESAs should be available to all families, regardless of income and special needs.” About 35 percent “strongly agree” with that statement. One out of five Ohioans (20%) disagree with that statement; 7 percent said they “strongly disagree.” In the comparison sample, needs-based split, respondents were asked if they agree with the statement, “ESAs should only be available to families based on financial need.” Fifty percent agreed with that statement, while 14 percent said “strongly agree.” Half of Ohioans (50%) said they disagree with means-testing ESAs, and 33 percent said they “strongly disagree.” More than four out of five current school parents (85%) agree that educational choice programs like ESAs should be available to all families, with more than one-third (36%) saying they “strongly agree.”

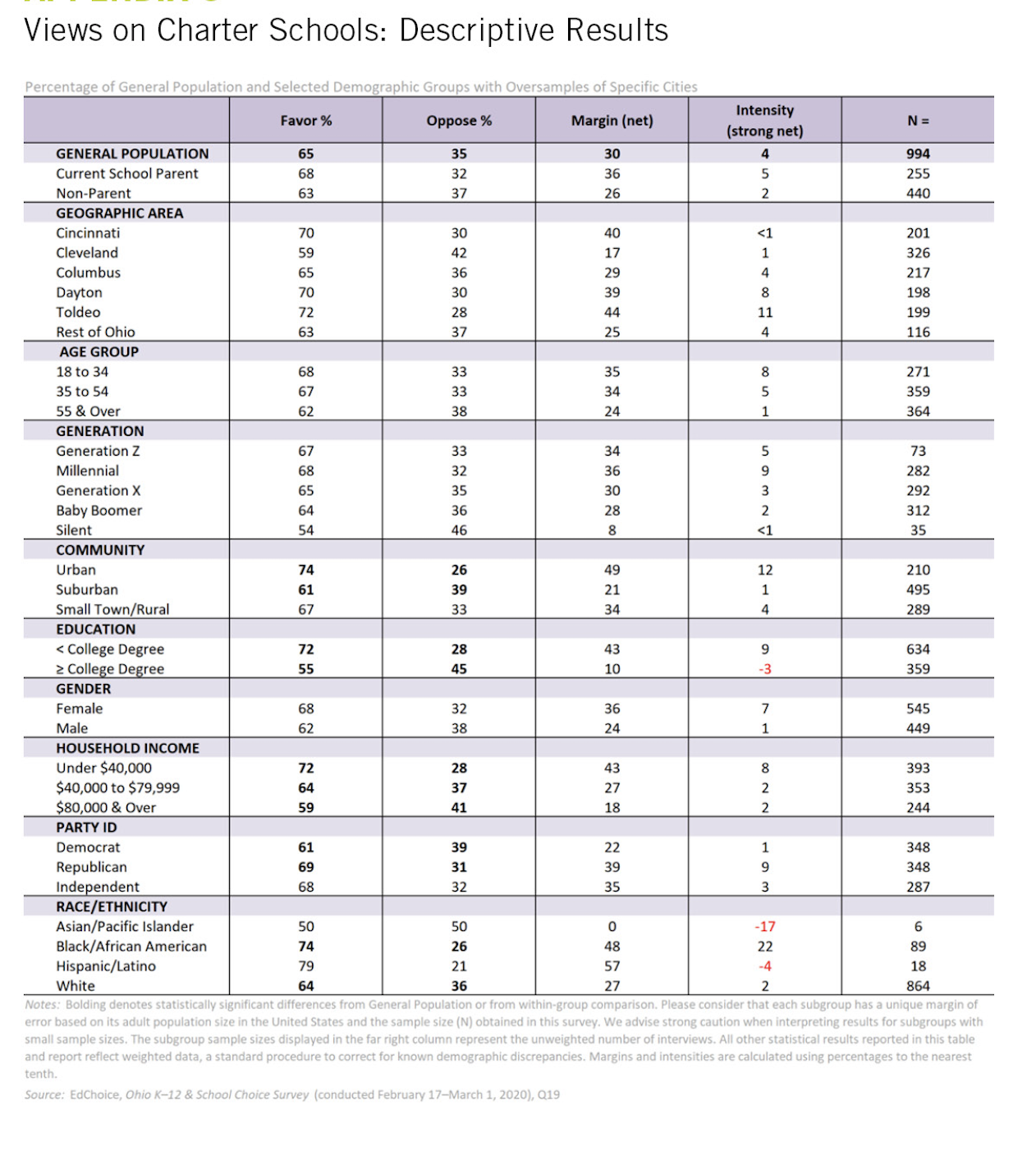

PUBLIC CHARTER SCHOOLS

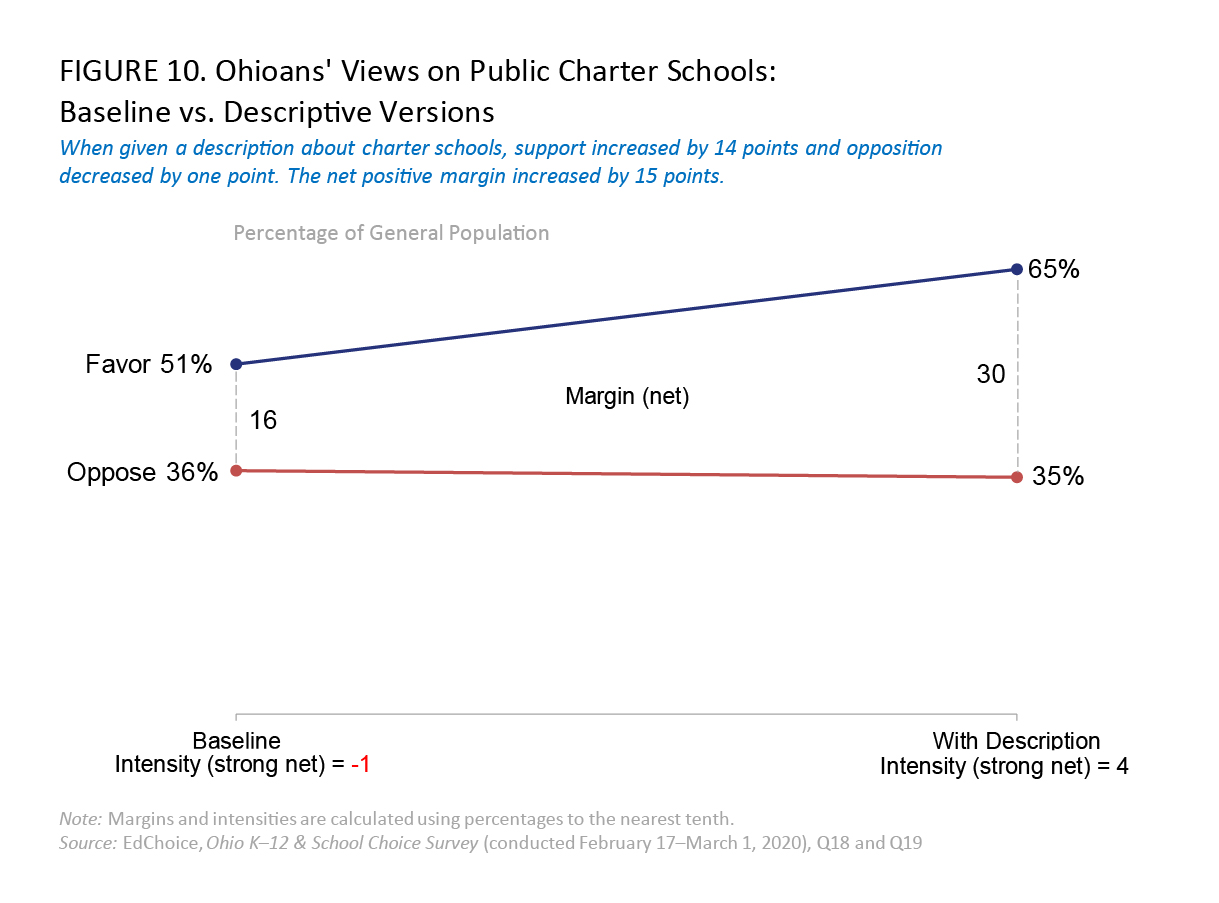

Ohio enacted its charter school law in 1997 and more than 600 public charter schools, sometimes referred to as community schools, have opened in the state since then.5 Respondents were asked two questions about charter schools, and Ohioans clearly support them, both before and after given a description.

Interviewers first asked for an opinion without offering any description. On this baseline question, 51 percent of respondents said they favored charters, and 36 percent said they opposed them. In the follow-up question, respondents were given a general description of a charter school in Ohio. With that information, support increased 14 points to 65 percent, and opposition decreased one point to 35 percent. The margin of support was large (+30 points).

Slightly more than one in 10 Ohioans (13%) said they had never heard of charter schools on the baseline item. The subgroups having the highest proportions saying they had never heard of charter schools are low-income earners (17%), younger Ohioans (17%), those without a college degree (18%), small town and rural residents (20%), Dayton residents (20%), and Generation Z (24%).

The margins of all subgroups observed are positive— and they exceed +10 percentage points for all subgroups with more than 35 respondents. The largest positive margins are among urbanites (+49 points), African Americans (+48 points), Toledo residents (+44 points), low-income earners (+44 points), and those without a college degree (+44 points). The subgroups exhibiting the lowest net positive margins for charter school favorability include college graduates (+10 points), Cleveland residents (+17 points), high-income earners (+18 points), and suburbanites (+21 points).

In addition:

- Urbanites (74%) were more likely to favor charter schools than suburbanites (61%).

- Those without a college degree (72%) were more likely to favor charter schools than college graduates (55%).

- Low-income earners (72%) were more likely to favor charter schools than middle-income earners (64%) and high-income earners (59%).

- Republicans (69%) were more likely to favor charter schools than Democrats (61%).

- African American Ohioans (74%) were more likely to favor charter schools than white Ohioans (64%).

SCHOOL TYPE ENROLLMENTS AND SATISFACTION

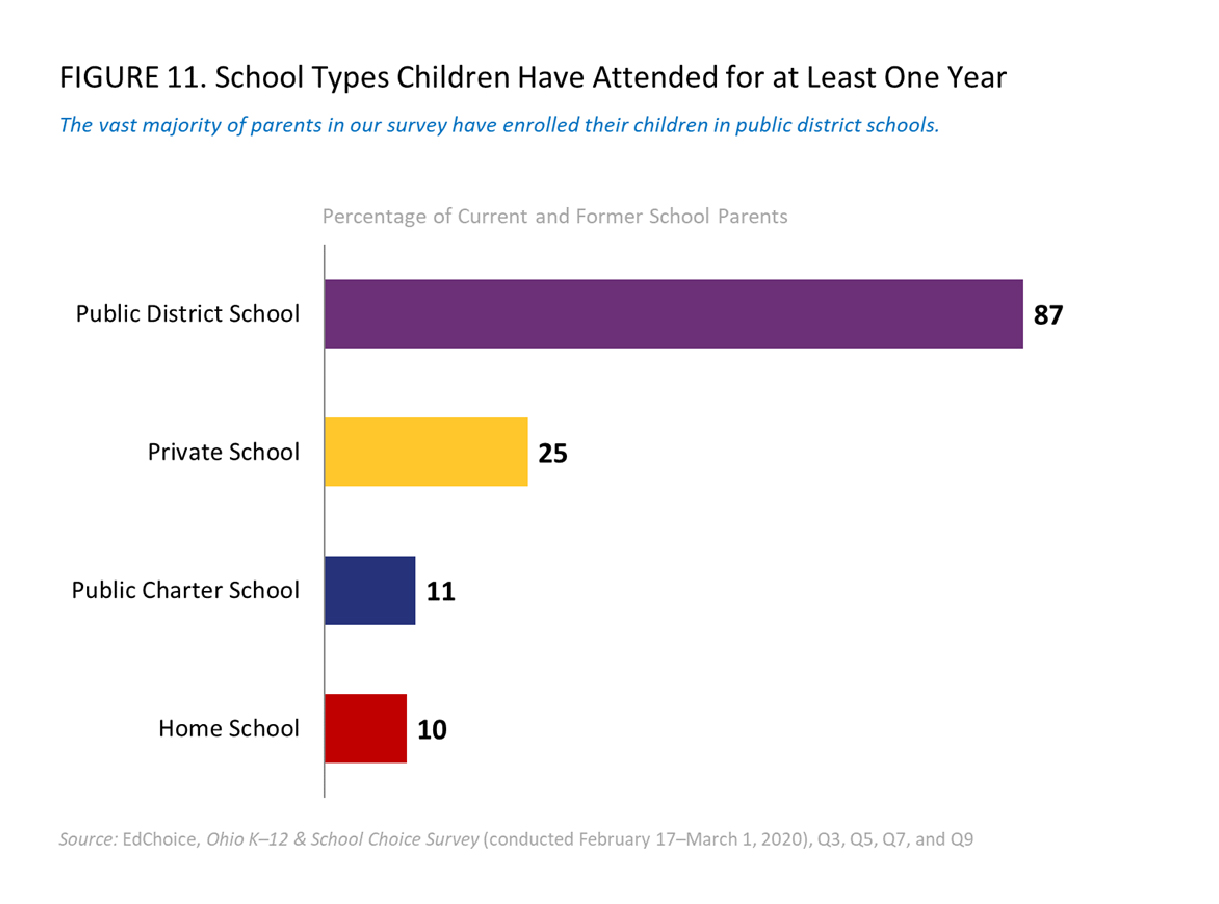

The vast majority of parents’ experiences occur in public district schools, with almost nine out of 10 parents surveyed (87%) having children who attended at least one year of public school. Figure 11 displays parents’ schooling experiences by type based on survey responses.

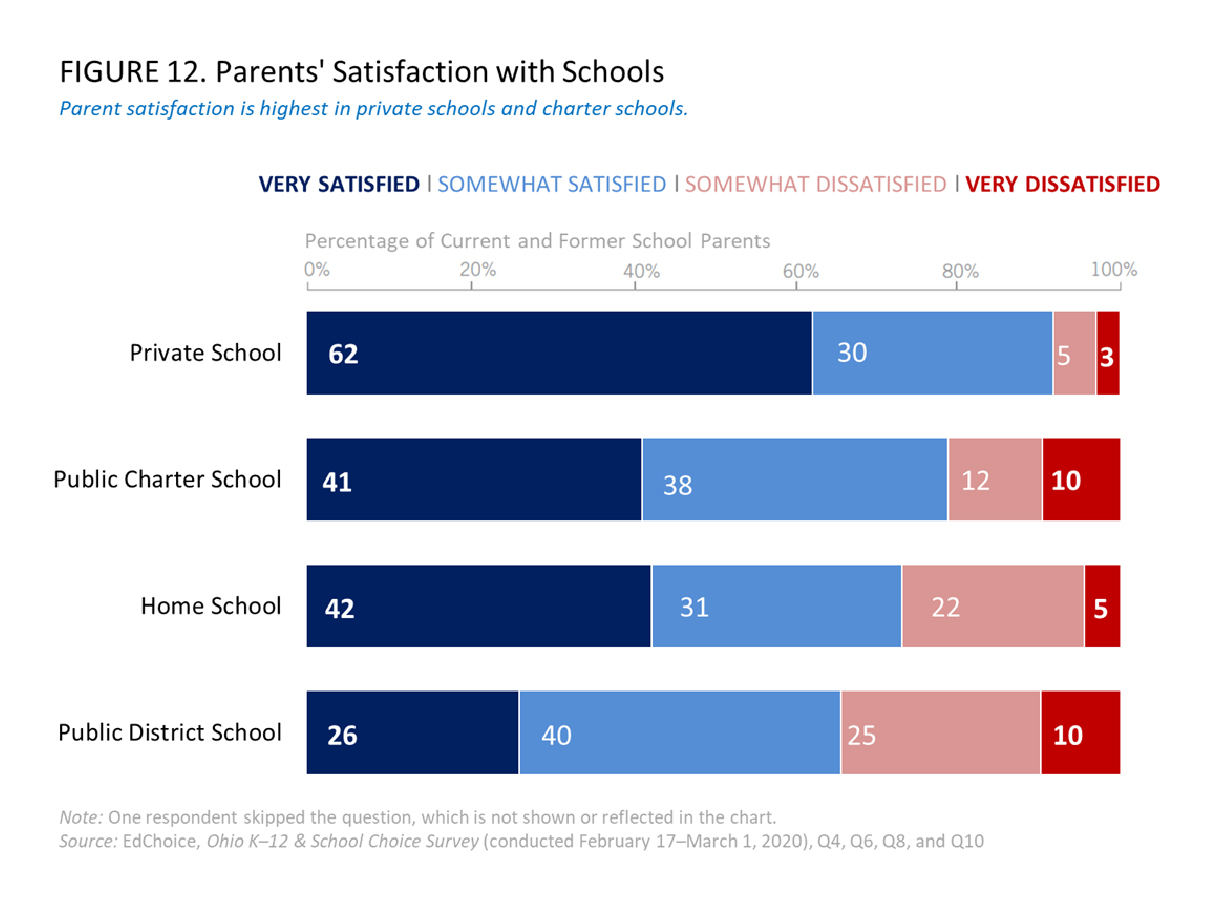

Current and former school parents are much more likely to say they have been satisfied than dissatisfied across all types of schools. More than nine out of 10 parents who have sent their children to private school (92%) expressed they were satisfied, the highest level of satisfaction among the four school types. The private school and charter school satisfaction margins (+84 points and +58 points, respectively) were greater than the margin observed for homeschooling (+46 points) and were about twice the satisfaction margin for district schools (+31 points). Parents were more than twice as likely to say they were “very satisfied” with private schools (62%) than district schools (26%).

GRADING LOCAL SCHOOLS

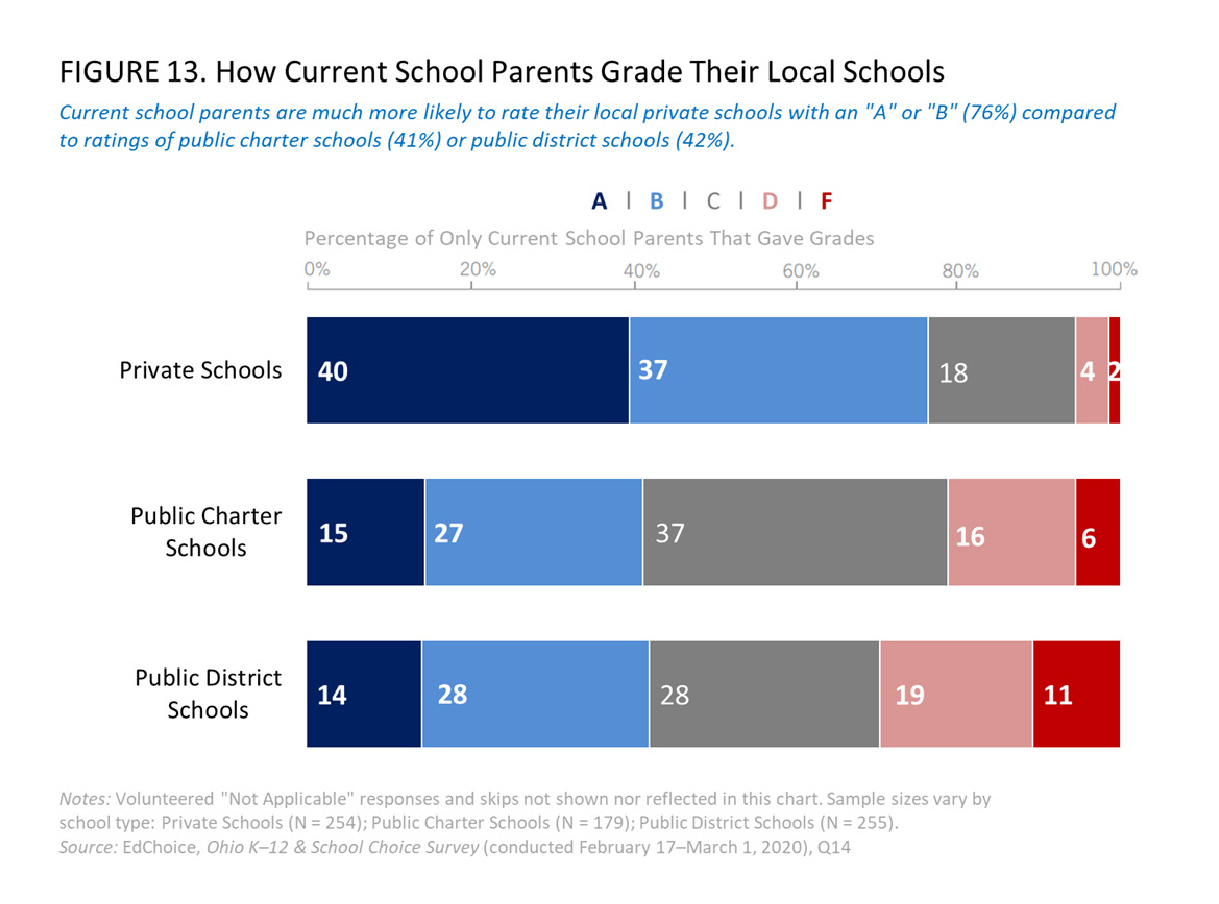

Ohioans are much more likely to give grades of “A” or “B” to private schools in their communities compared with their local public schools. When considering only those respondents with children in school who actually gave a grade, the local private schools (76% gave an “A” or “B”) fare better than regular public schools (42% gave an “A” or “B”) and public charter schools (41% gave an “A” or “B”). Only 6 percent of respondents give a “D” or “F” grade to private schools; 21 percent gave low grades to public charter schools; and 30 percent assign poor grades to area public district schools.

When considering all responses, we see approximately 66 percent of Ohioans give an “A” or “B” to local private schools; 34 percent give an “A” or “B” to local public charter schools; and 42 percent giving those high grades to regular local public schools. Only 5 percent of respondents give a “D” or “F” grade to private schools; 24 percent give the same low grades to regular public schools; and 16 percent suggest low grades for public charter schools.

It is important to highlight that much higher proportions of respondents do not express any view for private schools (14%) or public charter schools (24%), compared with the proportion that do not grade regular public schools (3%).

WHO SHOULD DECIDE AND SCHOOL TYPE PREFERENCES

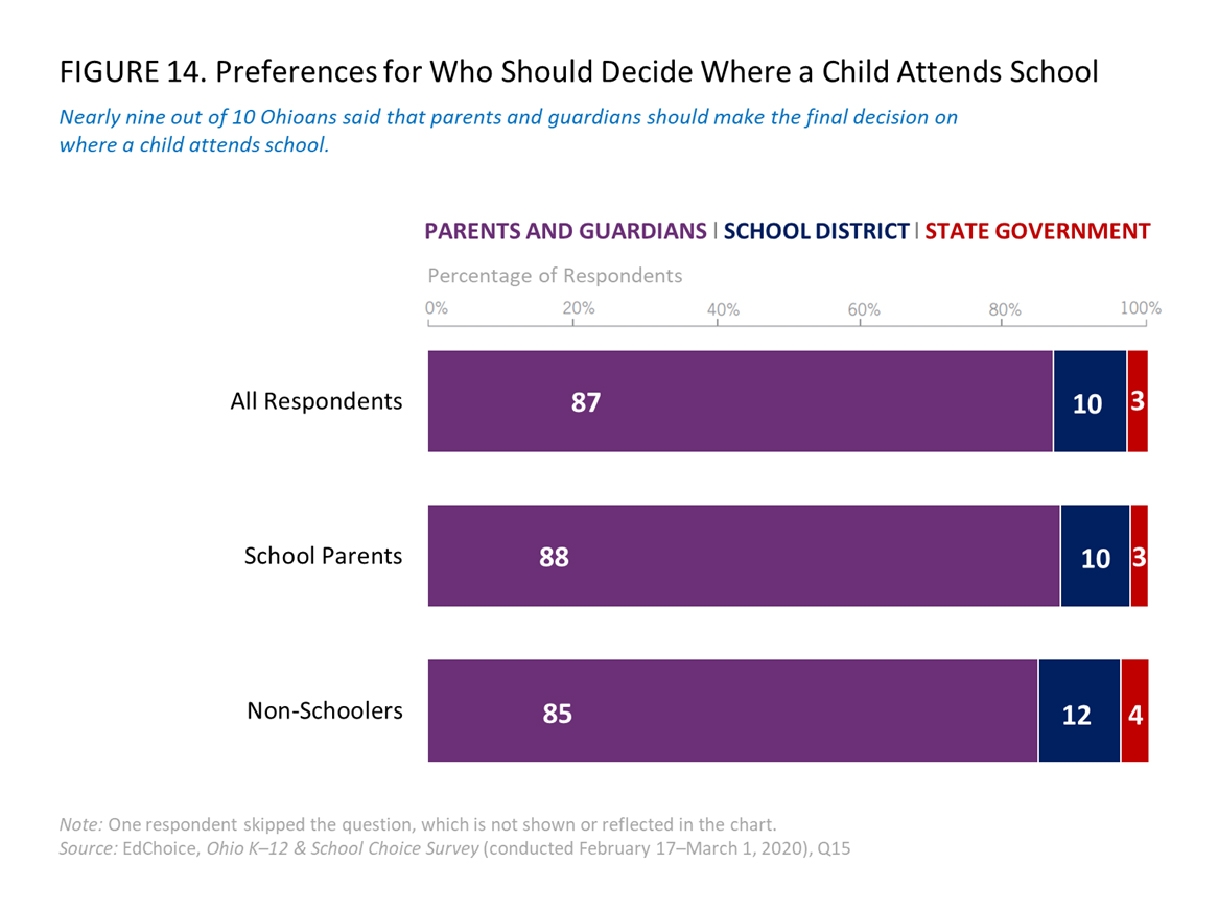

When asked who should decide where a child attends school, nearly nine out of 10 Ohioans (87%) said parents or guardians should decide. One out of 10 (10%) said the school district should decide, while 3 percent said the state should decide.

When asked for a preferred school type, more than half of Ohio parents would choose a private school (52%) as a first option for their child. Approximately one-fourth of respondents (26%) would select a regular public school. Eleven percent would choose a public charter school, and approximately one out of 10 would like to homeschool their child (11%).6

Private preferences signal a glaring disconnect with estimated school enrollment patterns in Ohio. About 82 percent of K–12 students attend public district schools across the state. Roughly 6 percent of students currently go to public charter schools. About 11 percent of students enroll in private or parochial schools, including about 3 percent doing so through the state’s five voucher programs. And it is estimated about 2 percent of the state’s students are homeschooled.7

In a split-sample experiment, interviewers asked a baseline question and an alternate version using a short phrase in addition to the baseline. When inserting the short phrase “… and financial costs and transportation were of no concern,” respondents are more likely to select private school compared to responses to the version without the phrase. The phrase’s effect appeared to increase the likelihood for parents choosing private schools (+3 point increase from baseline to alternate) or charter schools (+4 point increase). The phrasing effect depressed the likelihood of parents to choose a public district school (-3 point decrease) or home school (-4 point decrease). The inserted language in the alternate version appears to be a clear signal that can increase the attraction toward private schools while decreasing the likelihood to choose a public district school. Overall, 56 percent of Ohioans said that if financial cost and transportation were of no concern, they would select private schooling to obtain the best education for their child.

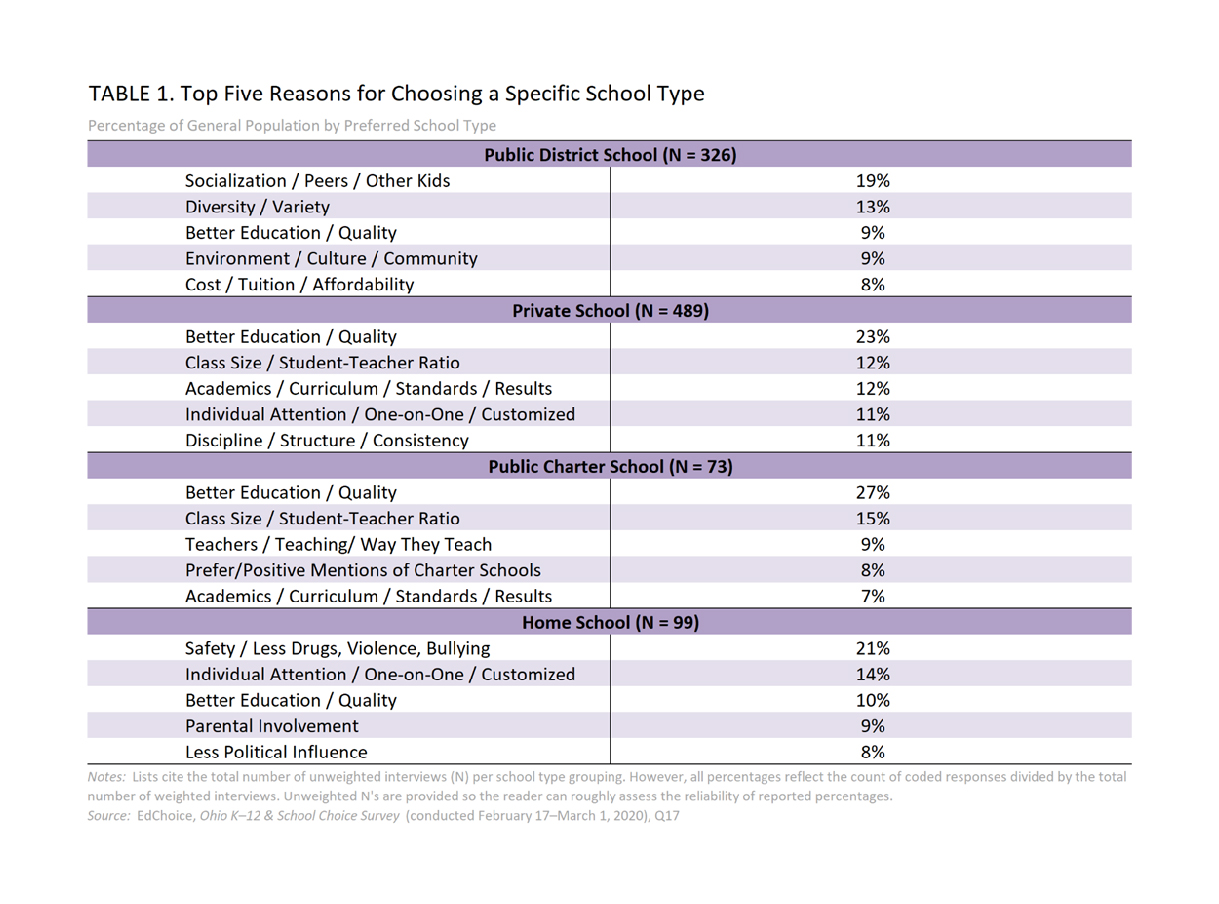

We asked survey respondents a follow-up question for the main reason they chose a certain type of school. Respondents choosing private school, public charter school, or homeschooling were more likely to prioritize “individual attention/one-on-one” and “class size/student-teacher ratio” than those selecting public district school. Nearly one-fourth of private school choosers (24%) and more than one-fifth of charter school choosers (22%) gave those reasons. Respondents that preferred district schools would most frequently say some aspect of “socialization” was a key reason for making their selection. We encourage readers to cautiously interpret these results because sample sizes were relatively small for the respondents that chose charter schools or homeschooling.

PERCEIVED DIRECTION OF K–12 EDUCATION

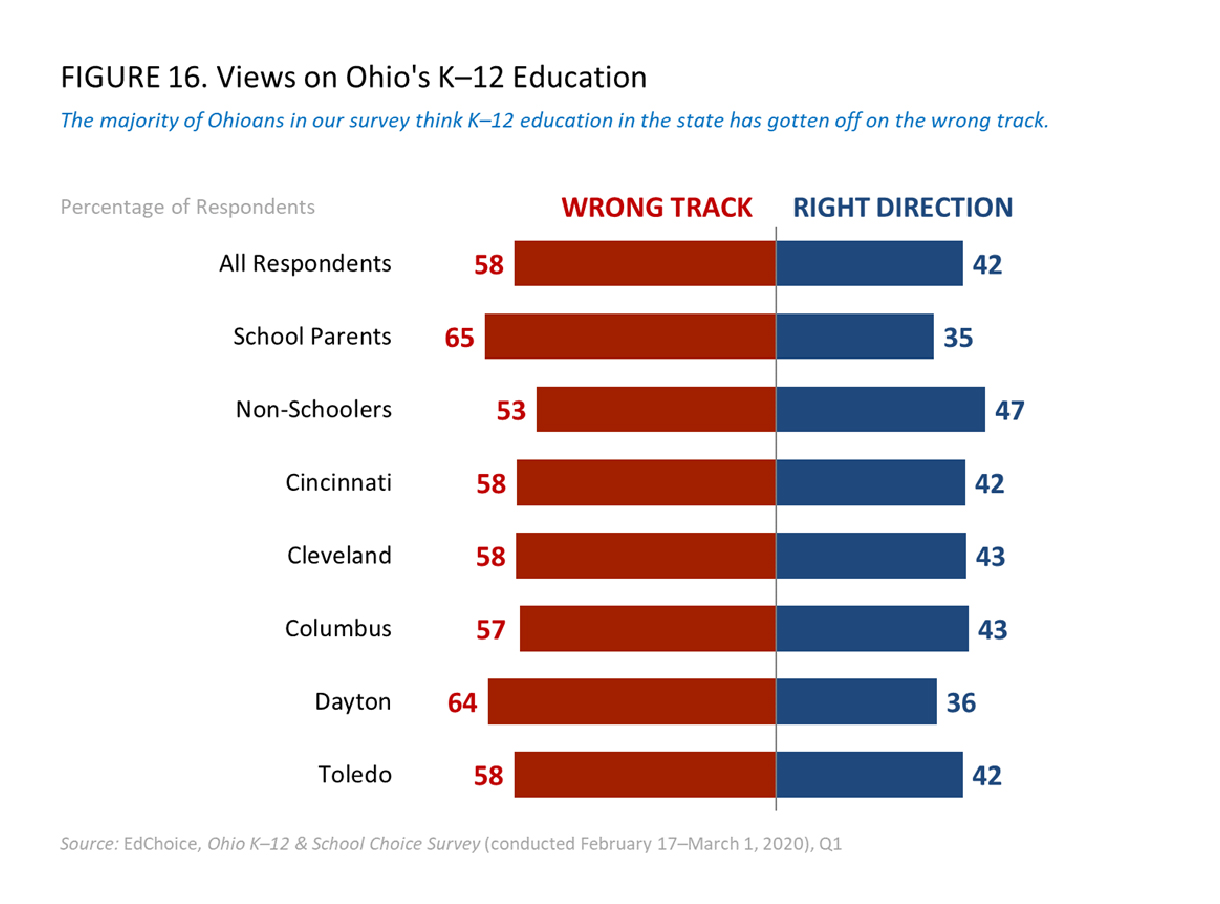

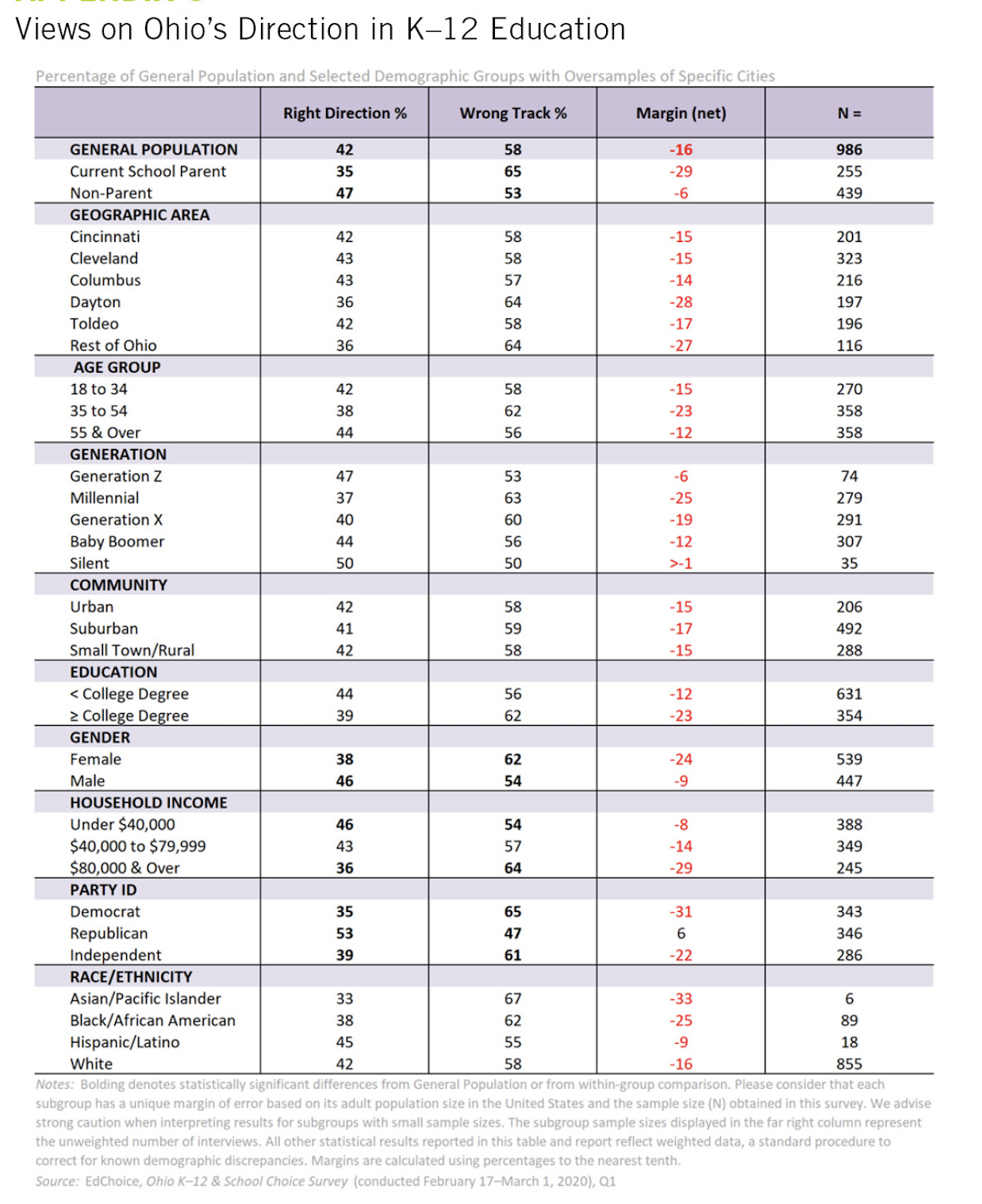

Nearly three-fifths of Ohioans (58%) say they think K–12 education in the state is on the “wrong track,” compared to 42 percent thinking it is going in the “right direction.” On balance, the mood for K–12 education tends to be negative, showcased by a negative margin of -16 points. Republicans were the only observed demographic to have a positive margin (+6 points).

In addition:

School parents (65%) were more likely to say “wrong track” than non-schoolers (53%).

Females (62%) were more likely to say “wrong track” than males (54%).

High-income earners (54%) were more likely to say “wrong track” than low-income earners (54%).

More than half of Republicans (53%) said “right direction” and were more likely to do so than Democrats (35%) and Independents (39%).

VIEWS ON SPENDING IN K–12 EDUCATION

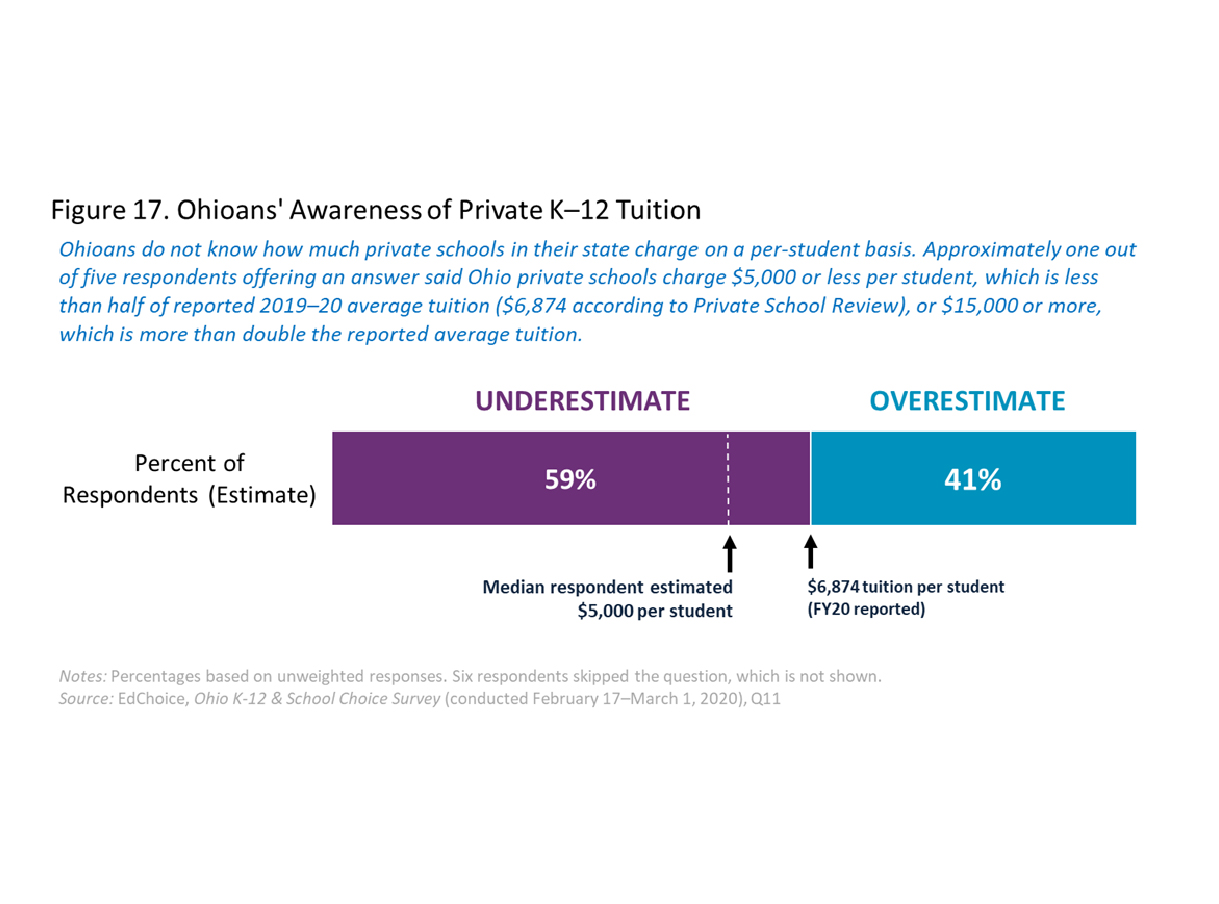

On average, according to Private School Review, Ohio private schools charge approximately $6,874 for tuition per student. Respondents were more likely to underestimate private school tuition (59%) than overestimate it (41%). Responses ranged from $0 to $30,000. The average response was $7,050, while the median response was $5,000. Nearly one-third of respondents (31%) provided an estimate of $10,000 or more, while nearly one-fourth (23%) provided an estimate of $2,000 or less.8

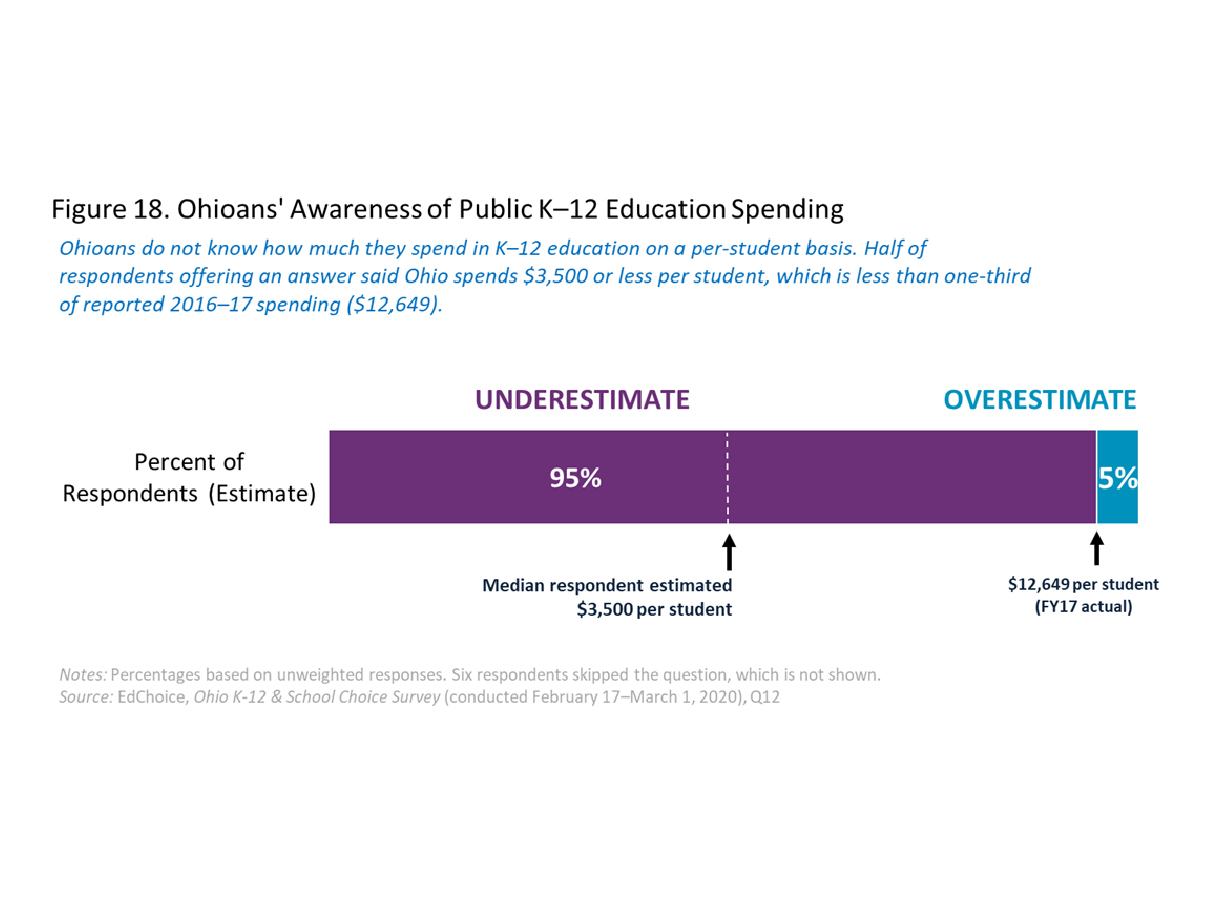

On average, Ohio spends $12,649 on each student in the state’s public schools, based on a cautious spending statistic termed “current expenditures.”9 Respondents were much more likely to underestimate public perpupil spending (95%) than overestimate it (5%). Responses ranged from $0 to $30,000. The average response was $4,942, while the median response was $3,500. Only four percent of respondents provided an estimate of $10,000 or more, while nearly two out of five respondents (37%) provided an estimate of $2,000 or less.

If instead of “current expenditures” we use “total expenditures” per student ($14,028 in 2016–17)—a more expansive federal government definition for K–12 education spending that includes capital costs and debt repayment—the proportion of Ohioans likely to underestimate per-pupil spending goes up another percentage point (96%). 10

Given an actual per-student spending statistic, Ohioans are much less likely to say public school funding is at a level that is “too low.” In a split-sample experiment, we asked two slightly different questions. On the baseline version, 56 percent of respondents said public school funding was “too low.” However, on the version where we included a statistic for average public per-pupil spending in Ohio ($12,645 in 2016–17; the most recent statistic available when the survey was fielded), the proportion that said spending was “too low” shrank by 30 percentage points to 26 percent.11

Appendix 1: Survey Project & Profile

Title: Ohio K–12 & School Choice Survey

Survey Funder: EdChoice

Survey Data Collection & Quality Control: Braun Research, Inc. (BRI)

Interview Dates: February 17–March 1, 2020

Sample Frame: Ohio Registered Voters (age 18+)

Sampling Method: Non-Probability, Stratified Online Panel

Language(s): English

Interview Method: Online

Interview Length: 10.1 minutes (average)

Sample Size and Margin of Error: Total (N= 1,265): ± 2.75 percentage points

Weighting? 17.6%

Response Rate: Yes; Age, County, Gender, Ethnicity, Race, Community Type, Income

Oversampling? Yes; Cincinnati, Dayton, and Toledo

Project Contact: Drew Catt, dcatt@edchoice.org

The authors are responsible for overall survey design; question wording and ordering; this report’s analysis, charts, and writing; and any unintentional errors or misrepresentations.

EdChoice is the survey’s sponsor and sole funder at the time of publication.

Appendix 2

Appendix 3

Appendix 4

Appendix 5

Appendix 6

Appendix 7

Appendix 8

Additional Resources

Acknowledgments

We are extremely grateful to the Ohioans that took the time to respond to the survey online. We are also grateful to Braun Research, Inc. for administering our survey and for data collection and quality control. We deeply appreciate the work of Michael Davey for making these pages look more professional and Jen Wagner for correcting spelling and grammar mistakes.

Any remaining errors in this publication are solely those of the authors.

Endnotes

- Martin F. Lueken (2018), Fiscal Effects of School Vouchers: Examining the Savings and Costs of America’s Private School Voucher Programs, retrieved from EdChoice website: https://www.edchoice.org/wpcontent/uploads/2018/09/Fiscal-Effects-of-SchoolVouchers-by-Martin-Lueken.pdf

- Stephen Q. Cornman, Lei Zhou, Malia R. Howell, and Jumaane Young (2020), Revenues and Expenditures for Public Elementary and Secondary Education: FY 17 (NCES 2020-301), retrieved from National Center for Education Statistics website: https://nces.ed.gov/ pubs2020/2020301.pdf

- Authors’ calculations; EdChoice (2020), The ABCs of School Choice: The Comprehensive Guide to Every Private School Choice Program in America, 2020 edition, retrieved from https://www.edchoice.org/ wp-content/uploads/2020/01/2020-ABCs-of-SchoolChoice-WEB-OPTIMIZED-REVISED.pdf

- For terminology: We use the label “current school parents” to refer to those respondents who said they have one or more children in preschool through high school. We use the label “former school parents” for respondents who said their children are past high school age. We use the label “non-parents” for respondents without children. For terms regarding age groups: “younger” reflect respondents who are age 18 to 34; “middle-age” are 35 to 54; and “seniors” are 55 and older. Labels pertaining to income groups go as follows: “low-income earners” < $40,000; “middleincome earners” ≥$40,000 and < $80,000; “highincome earners” ≥ $80,000. We adapt the Pew Research Center’s classifications of generational cohorts for this report: Generation Z (1997 or earlier) Millennial (1981–1996); Generation X (1965–1980); Baby Boomer (1946–1964); and Silent Generation (1928–1945). Pew Research Center, Generations and Age [Web page], accessed March 5, 2020, retrieved from http://www. pewresearch.org/topics/generations-and-age

- Center for Research on Education Outcomes (2019), Charter School Performance in Ohio, retrieved from: https://credo.stanford.edu/sites/g/files/ sbiybj6481/f/oh_state_report_2019.pdf; Education Commission of the States (2020), Charter Schools: State Profile – Ohio [Web page], accessed March 11, 2020, retrieved from: http://ecs.force.com/mbdata/ mbstprofile?Rep=CSP20&st=Ohio

- Unless otherwise noted, the results in this section reflect the composite average of split-sample responses of current and former school parents to both splits for question 16.

- Authors’ calculations; U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, Common Core of Data (CCD), “Public Elementary/Secondary School Universe Survey”, 2017-18 v.1a, “State Nonfiscal Public Elementary/Secondary Education Survey”, 2017-18 v.1a, via ElSi tableGenerator, retrieved from https:// nces.ed.gov/ccd/elsi/tableGenerator.aspx; Andrew D. Catt (2020, January 28), “U.S. States Ranked by Educational Choice Share, 2020” (Blog post), retrieved from EdChoice website: https://www.edchoice.org/ engage/u-s-states-ranked-by-educational-choiceshare-2020

- Private School Review, Ohio Private Schools by Tuition Cost [Web page], accessed March 11, 2020, retrieved from: https://www.privateschoolreview. com/tuition-stats/ohio

- “Current Expenditures” data include dollars spent on instruction, instruction-related support services, and other elementary/secondary current expenditures, but exclude expenditures on capital outlay, other programs, and interest on long-term debt. “Total Expenditures” includes the latter categories and sometimes others. Stephen Q. Cornman, Lei Zhou, Malia R. Howell, and Jumaane Young (2020), Revenues and Expenditures for Public Elementary and Secondary Education: FY 17 (NCES 2020-301), retrieved from National Center for Education Statistics website: https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2020/2020301.pdf

- Ibid.

- U.S. Census Bureau, 2017 Public ElementarySecondary Education Finance Data: Summary Tables [Data file], accessed January 7, 2020, retrieved from https://www2.census.gov/programs-surveys/schoolfinances/tables/2017/secondary-education-finance/ elsec17_sumtables.xls