Introduction

The big yellow school bus is an iconic image of American education. It is a central feature in the stock images that accompany articles and reports about schools. It plays a role in our culture, with school bus scenes in movies ranging from Forrest Gump to Billy Madison. We even sing nursery rhymes to our children about how its wheels go ‘round and ‘round. It is not surprising that student transportation plays such a seminal role in our education system, given our vast geography and sprawling cities.

Busing played a large role in the civil rights movement and the effort to desegregate schools in the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s. It was a controversial practice that is still a matter of debate 50 years after it first emerged in our nation’s cities.

School transportation is inextricably linked to school choice. Transportation, or the lack thereof, can be a huge barrier to families exercising choice. Simply because a state authorizes the creation of charter schools or grants vouchers to families looking to send their children to private schools doesn’t mean that those children will actually be able to attend those schools. They have to be able to get there safely, on time, and ideally after spending as little time on the bus as possible.

In a 2017 Brookings Institution study, Matthew Chingos and Kristin Blagg used school location data to estimate the number of potential schools of choice within reasonable commuting distance of American families.1 They found that 83 percent of American families had two or more traditional public schools in their school district within five miles of their home. They found that 54 percent had two or more public schools across district lines; 46 percent had a charter school; and 82 percent had a private school within that same radius. There are lots of choices out there for families, but they are no good if children can’t get to them.

Figuring out transportation policy will be key to realizing the promise of school choice. It is much easier to efficiently transport students to neighborhood schools when districts draw attendance boundaries and catchment areas and then create bus routes within them. As children need to get across cities or counties to attend the school of their choice, efficiently moving them becomes much harder.

Policies vary from state to state, district to district, and school sector to school sector. Whether or not students are provided with transportation can vary based on their proximity to their school, their age, the type of school they attend, the existing public transportation infrastructure in the city in which they live, and other factors. Policy plays a role as well. In some locations, laws provide guarantees for students that they will have free transportation to the school of their choice. In others, students are on their own.

Research Questions

Almost every question in American education can be answered with the phrase “it depends.” Given the 14,000 school districts and patchwork of charter school and private school choice laws around the country, there is no one simple, straightforward way of describing transportation policy as it relates to school choice. But what can we describe? Can we come to a better understanding, at least when it comes to school choice, about what opportunities students do and do not have at the state or local level? Finding these answers is the goal of this primer.

To do so, we scoured the state statutes and regulations regarding pupil transportation and various kinds of school choice, including interdistrict transfer programs, charter schooling, and private schooling. Which states allow for the support or subsidization of pupil transportation to schools of choice? To some schools and not others? Under what circumstances? These are some of the questions we set out to answer.

But before we get there, it is important to linger for a minute on the growing research on pupil transportation and school choice. Better understanding both the costs and the benefits will help lawmakers craft better policies going forward.

What We Know

More and more research is being conducted on the relationship between pupil transportation, school choice, and student outcomes. In 2009, Paul Teske, Jody Fitzpatrick, and Tracey O’Brien published Drivers of Choice: Parents, Transportation, and School Choice in which they surveyed 600 parents, split between Denver and Washington, D.C. They found 25 to 40 percent of parents said that transportation options affected their choice of school, and 80 percent of parents would be willing to travel farther to a higher-quality school if there were better transportation options available.2 A 2018 EdChoice report on parents participating in the Florida Tax Credit Scholarship Program found transportation is among the top challenges families face when exercising private school choice, (particularly families with very low incomes) with only 6 percent of private school choice parents reporting their child rides a school bus or takes public transportation to their private school.3

In 2017, the Urban Institute convened the Student Transportation and Educational Access Working Group, which published a series of papers looking at student transportation in Denver, Detroit, New Orleans, New York City, and Washington, D.C. They summarize their key findings in this way:

- “All five cities provide transportation, but availability varies by school. Although each city offers yellow bus or public transit to students’ neighborhood schools, transportation to nonneighborhood and charter schools varies.

- “Most students do not live further than a 20-minute drive to their schools, but travel patterns vary across age and demographic groups. Older students travel farther to school than younger students, and black students travel farther than white and Hispanic students.

- “Access to a car can significantly increase the number of schools available to a family. In nearly every grade, students have access to 10 or more schools within a 15-minute drive but typically have access to fewer than 10 schools when traveling for the same amount of time on public transit.

- “Students from low-income families typically do not travel farther to school than their comparatively advantaged peers.

- “Charter school students, on average, do not always travel farther than their peers in traditional public schools.”4

As part of that project Carolyn Sattin-Bajaj of Seton Hall University published “It’s Hard to Separate Choice from Transportation” Perspectives on Student Transportation Policy from Three Choice-Rich School Districts, an in-depth look at Detroit, New Orleans, and New York City. After interviewing both district and charter school leaders, she summarized their concerns and challenges. The district officials lamented the large geographic areas for which they were responsible and the high levels of student mobility that together make transportation complicated and expensive. Adding to the expense of pupil transportation—measured to be $936 per pupil nationwide by the National Center for Education Statistics in 2014–15, which is up 73 percent since 19805 —is the specialized and often individualized, door-to-door transportation mandated by law for students with special needs. Administrators were also concerned with the limited public transportation options of which students can take advantage.6 Charter leaders were concerned with student safety, the logistical demands of figuring out bus routes, a lack of control with the drivers and bus companies themselves and the often difficult contracts that have to be negotiated with them, the time that students spend on the bus, and all of the associated costs.7

On a statewide level, EdChoice released a geospatial analysis in 2018 examining drive times for K–12 students to schools of choice in Indiana.8 Despite being a state rich with school choice policies, the authors identified more than 24,000 K–8 students (roughly 3 percent of the state’s elementary and middle school students) who had a 30-minute or more one-way drive from a charter, magnet, or voucher-participating private school. Indiana high school students were especially likely to live far from schools of choice. The authors found more than 45,000 high school-aged students (roughly 10% of the state’s total) are a 30-minute or longer one-way drive from charter, magnet, or voucher-participating high schools. The majority of those students resided in small towns and rural areas.9 Nationally, EdChoice’s survey work found parents in rural and small town communities were more likely than suburban and urban parents to say they have moved to be closer to a child’s school.10

EdChoice also found in a 2017 survey of parents that at least nine out of 10 Indiana students spend 30 minutes or less traveling to school one way, regardless of schooling sector.11 In Florida, another choice-rich state with five private school choice programs, the vast majority of private school choice parents (80%) drive their students to school most days, according to a 2018 EdChoice survey.12 A majority of Florida private school choice parents reported their child commutes 15 minutes or less one way to school, while less than 10 percent reported the school commute taking more than 30 minutes.

But even with all of the challenges, two papers produced by an Urban Institute working group offer evidence that the juice is worth the squeeze. Patrick Denice and Bethany Gross analyzed 3,100 student transportation patterns in Denver and found 1,000 “super travelers” who traveled particularly longer than the district average distances to attend their top-choice school. Those schools had “better academic outcomes, fewer disciplinary incidents, and more advanced courses and dual-language programs than schools closer to home.”13

Sarah Cordes and Amy Ellen Schwartz looked at students taking advantage of transportation options provided to them in New York City and found “those who use transportation attend significantly better schools than their peers attending nearby choice schools, with bus riders experiencing the largest gains in school quality.14 Further, transportation appears to play a particularly important role for black and Hispanic bus riders, who are 30 to 40 percentage points more likely to attend significantly better schools than their same-race peers who attend choice schools but do not use transportation.”15

As Bethany Gross summarized in a 2019 article in Education Next, “we found that students who choose to travel for school do get something for their effort.”16

Methods

To understand the national landscape, we needed to understand state law and how it has been interpreted. To do so, we conducted a systematic search of all 50 state education statutes to identify the language related to pupil transportation. We utilized a legal research platform to conduct this review, narrowing searches within states’ education codes and cross-referencing with states’ separate transportation codes when referenced by student transportation laws.

Many states contain distinct pupil transportation sections within their education codes; we reviewed those in their entirety to discern how states identify, fund, and delineate responsibility for transporting charter, private, and open enrollment students.17 For those states without such specific sections, as well as those states whose pupil transportation sections were unclear as to choice students, we input choice search terms related to private schooling, charter schooling, and openenrollment/inter-district transferring that fell within 15 words of transportation-related terms.18

We then looked at how the laws apply to three types of school choice: inter-district choice, charter schooling, and private schooling. For states where the statutes were unclear, we searched education regulations using the same search process we used for state statutes. Where appropriate, we also sought out state court cases that ruled on or clarified pupil transportation laws. These searches were conducted in the summer of 2019, and the statutes, regulations, cited are current as of the conclusion of spring 2019 legislative sessions.

Finding these statutes and regulations allows us to identify which states provide support for these three types of school choice. We identify a state as providing this support if the sector is on equal or close-to-equal footing with public school students regarding transportation rights or rights of families or schools to transportation funds. States would only meet this standard if statute, regulation, and/ or case law explicitly provided for that sector’s publicly provided transportation or funding on or near equal footing with public school students.

In some instances, this takes the form of state mandates. But it is difficult to standardize mandates across states, sectors, and, ultimately, education stakeholders such as students, schools, and school districts. Because of this, we coded transportation policies for charter, private, and inter-district transfer students so that they would be essentially equivalent compared to public school districts and students within a given state as opposed to being equivalent from one state or sector to the next. For instance, a state may provide for pupil transportation of both charter and private school students within district boundaries and thus be providing essentially equivalent transportation services as compared to the school district; however, transportation of resident students to charter and private schools outside one’s school district would be considered exceptional transportation services when compared to resident public school districts unless the state also mandates district-provided transportation services for open enrollment students.19

It is worth noting that, generally, state laws do not mandate districts transport all public school students. Only after certain baseline factors are met, such as a student’s minimum distance from his or her school or potentially hazardous pedestrian conditions, do a majority of states mandate districtprovided pupil transportation. These baselines were also considered when comparing pupil transportation policies across sectors.

Omissions of choice schools within our search results were treated and interpreted as not allowing for those students’ public transportation, as the education codes almost exclusively defined pupil transportation as related to public school students and school districts.

It is also important to delineate state-based pupil transportation laws and the responsibilities these laws impose on school districts from individual districts’ transportation policies. This report takes a state-based approach to transportation policy, but individual districts may have more choice-friendly transportation offerings than imposed by a state. The pupil transportation landscape described below, though, hopefully offers a high-level view of which states allow for families to exercise educational choices via the same or similar pupil transportation mechanisms as those who choose their residentially assigned schools.

The Pupil Transportation Landscape

The existing research literature tells us that allowing students to travel to schools outside of their immediate surroundings opens important opportunities for them. Given this context and information, how can we make it easier for children to get to the schools of their choice?

Transportation policy, like most things in education policy, differs from state to state and city to city.20 While the national pupil transportation landscape can appear more tangled than a school district’s overlapping bus routes, commonalities and patterns may be found among the states examined below.

Broadly speaking, states fund pupil transportation through their funding formulas by allocating aid to school districts that is restricted to providing transportation services. Depending on the state, school districts may supplement transportation costs from local funds. These per-pupil aid amounts typically differ between students with Individualized Education Plans (IEPs) and students without special needs, the former of which are guaranteed transportation to, from, and between schools as a “related service” per the Individuals with Disabilities Act (IDEA).21 But IEP status is not the only variable, as population density, distances traveled, and a host of other variables can affect the cost of providing transportation.

School districts then use funds to transport students or contract with private transportation companies which are often themselves subject to state regulation pertaining to school bus safety, background checks of drivers, and emissions standards. Interestingly, many states impose these or similar pupil transportation regulations on private and charter schools regardless of whether pupil transportation at these schools is funded by the state or district. The districts and pupil transportation companies (or in-house transportation departments) work together to create bus routes, although some state departments of education offer route-planning resources as well as mandate reporting requirements related to routes.22 In some urban and suburban areas, districts may also utilize existing public transportation options by either reimbursing families for fares or partnering with regional transportation agencies to provide eligible students with fare cards.23

The district-transportation relationship cannot be overstated when it comes to pupil transportation: States impose the lion’s share of the responsibility of pupil transportation on the district. Districts do not have a strong incentive to provide transportation to schools that they see as competition for students and resources. But states still play an important role in shaping pupil transportation policy. The amount states fund pupil transportation is crucial to the district role, but states may also determine which students are legally eligible for transportation services. This eligibility is also defined in terms of distance in statute, but many states also take a school sector approach to pupil transportation.

As we will note in the text in each section there are lots of states that put serious constraints and conditions on pupil transportation funding. Students might be allowed support to transfer to another school district, but not just any school district. Students might be allowed to ride the bus to their private school, but only if they are on an existing bus route. Or, students might be able to access funds, but only after traditional public schools have first crack at them. These practices, while ostensibly identifying a state as one that supports pupil transportation for that kind of school choice, in practice means that very few students are able to take advantage of it. The devil, as usual, is in the details.24

Inter-District Choice

Allowing students to cross district lines has been a popular, if controversial, form of school choice policy for decades now. Inter-district choice has often been used as a tool for desegregation, as moving children from suburbs to urban centers and vice versa was the only way to make the math of integration work in cities that were heavily residentially segregated. But desegregation is not the only reason that a state might pursue a policy of inter-district choice. States like Indiana and Arizona have instituted wide-sweeping interdistrict choice programs, partially in response to the competition that private school choice and charter schools have placed on public schools. If, the logic goes, there is going to be school choice, districts want to keep it within their sector. Other states have pursued inter-district choice without the threat of private school choice or vouchers.25

Inter-district choice often requires traveling long distances. Because by definition inter-district choice requires moving from one district to another, children without parents who are able to transport them are less likely to be able to take advantage of the program. Some states have responded by providing transportation to students participating in inter-district choice programs.

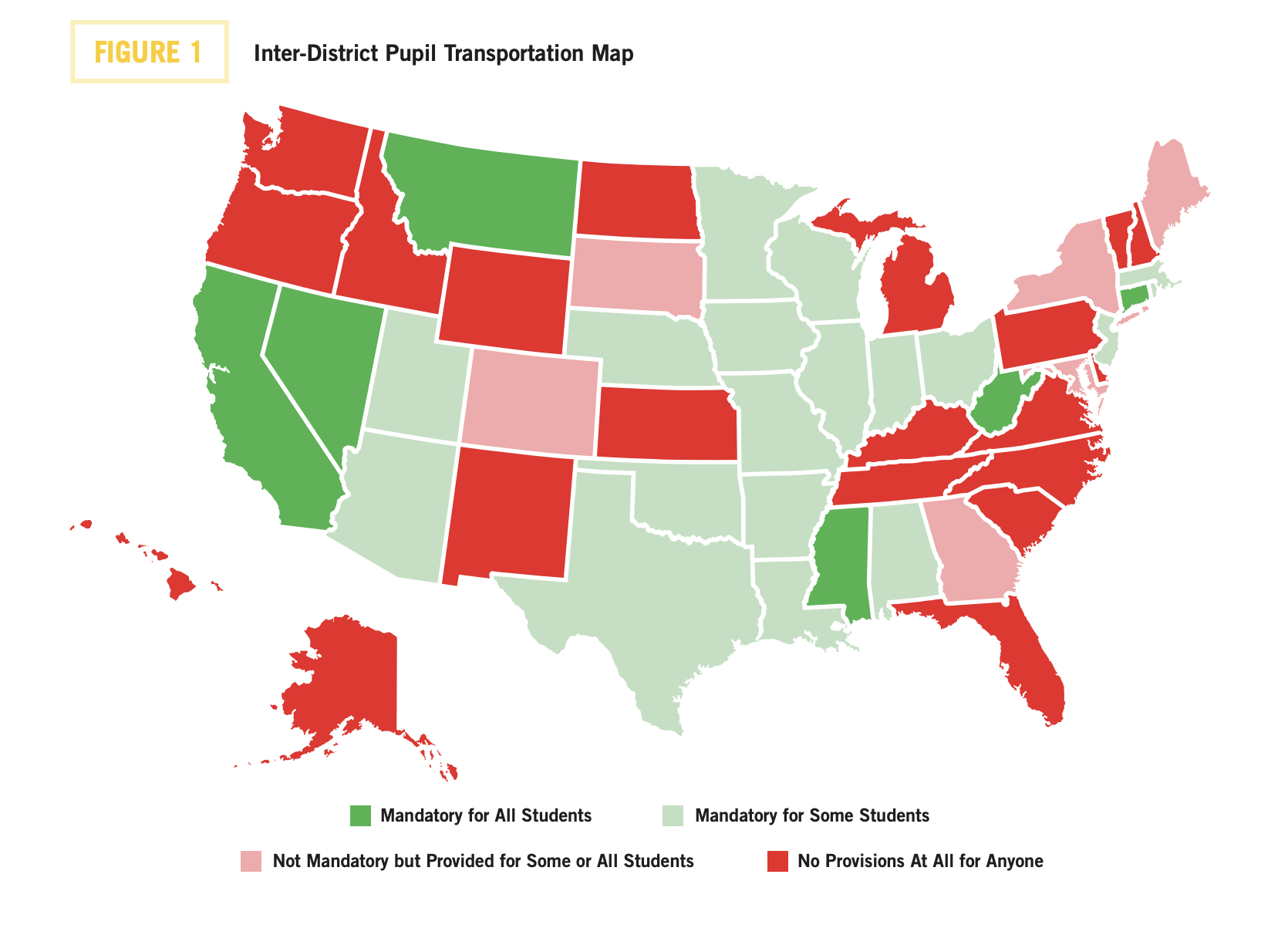

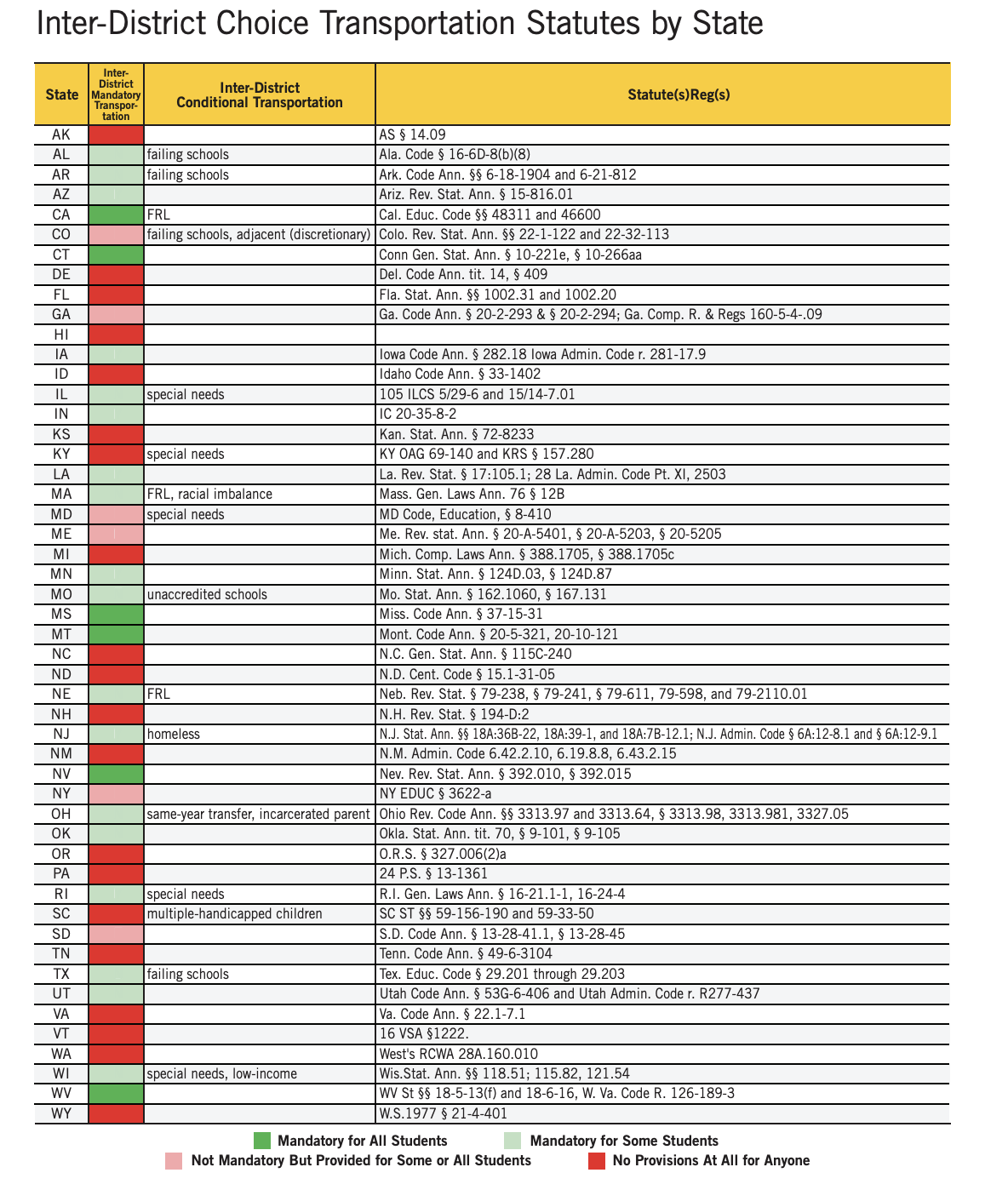

Figure 1 shows the 30 states that have at least some legal provision allowing for the public funding of inter-district student transportation. Of those states, six mandate pupil transportation services for open enrollment students at a level equivalent or roughly equivalent standard to intra-district students. Conditionally-mandated open enrollment transportation policies include students zoned to “failing” public schools, students eligible for the federal free and reduced-price (FRL) lunch program, students with special needs, students zoned to unaccredited schools, and homeless students. One state (Massachusetts) also has an open enrollment pupil transportation policy related to its law addressing racial imbalances in public schools.

Exactly how these policies manifest themselves is complicated. In Alabama, for example, transportation is only provided if the student is leaving a failing traditional public school. In California, the receiving district is responsible for transportation. The same is true in Minnesota, but only up to the district’s boundaries. In Iowa, transportation is only provided for students with special needs. In West Virginia, county boards are in charge of determining transportation agreements for students wishing to utilize interdistrict transfers. In Rhode Island, support is provided, but only within state-determined transportation zones. The full list of state provisions, including the relevant citations to state law are available in Appendix 1.

Charter Schools

Charter schools are a large and growing segment of the school choice landscape. According to the National Center for Education Statistics, more than 3 million students attend charter schools, up from just 400,000 in the year 2000.26 Charter schools are independent public schools that draw from a broader catchment area than residentially assigned public schools. This often places a burden on students to be able to get to school.

States that approve charter schools often require founders to detail how the schools plan to address students’ transportation needs in their submission proposals. Illinois, for example, requires a description of the charter school as well as how it plans to address the transportation needs of lowincome students.27

Aside from transportation proposal requirements placed on charter schools, school districts can also be mandated to transport charter school students. These mandates, though, are normally subject to various limitations, such as only necessitating transportation for students or schools within various district boundaries and limiting transportation to synchronous district busing routes.28

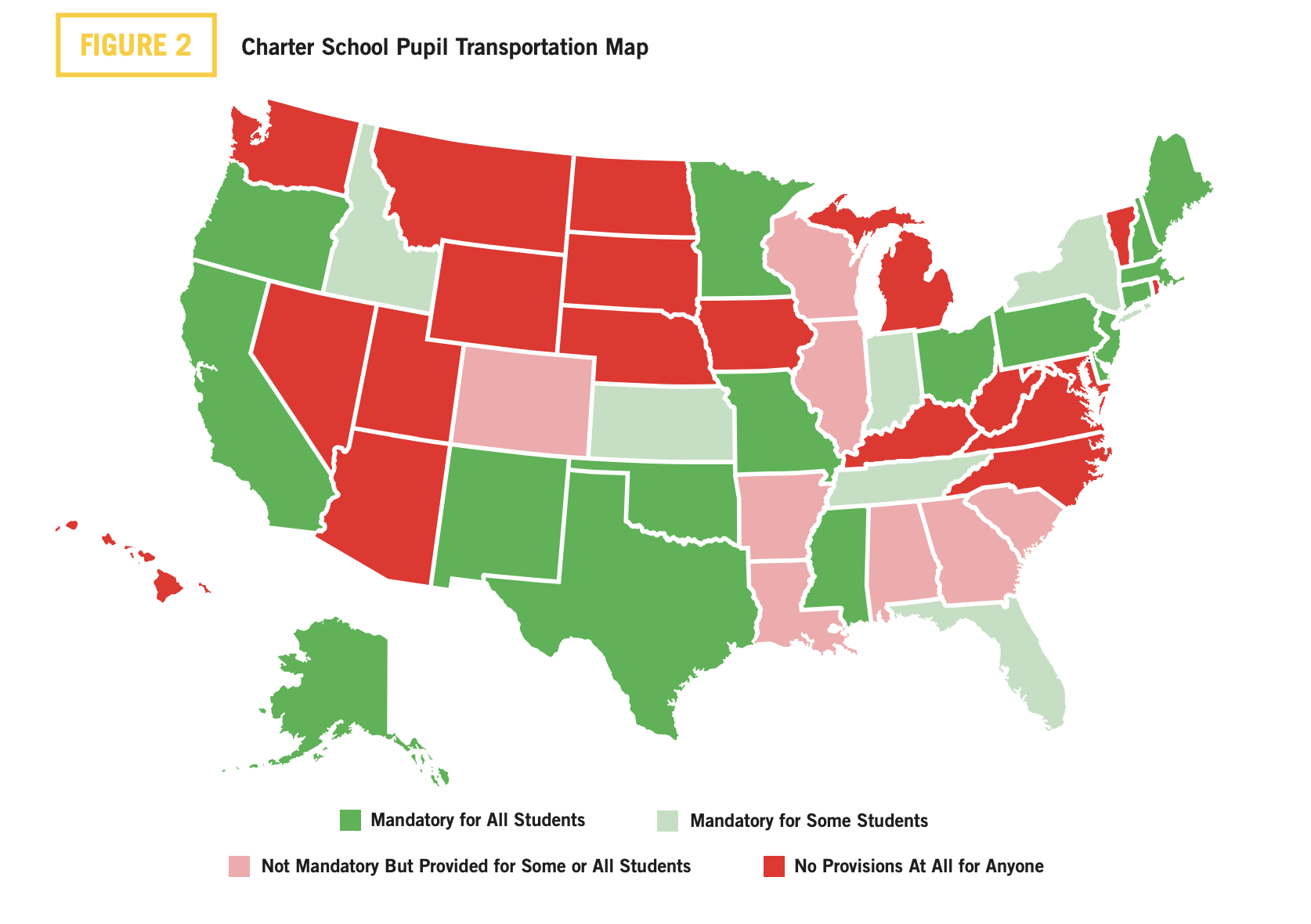

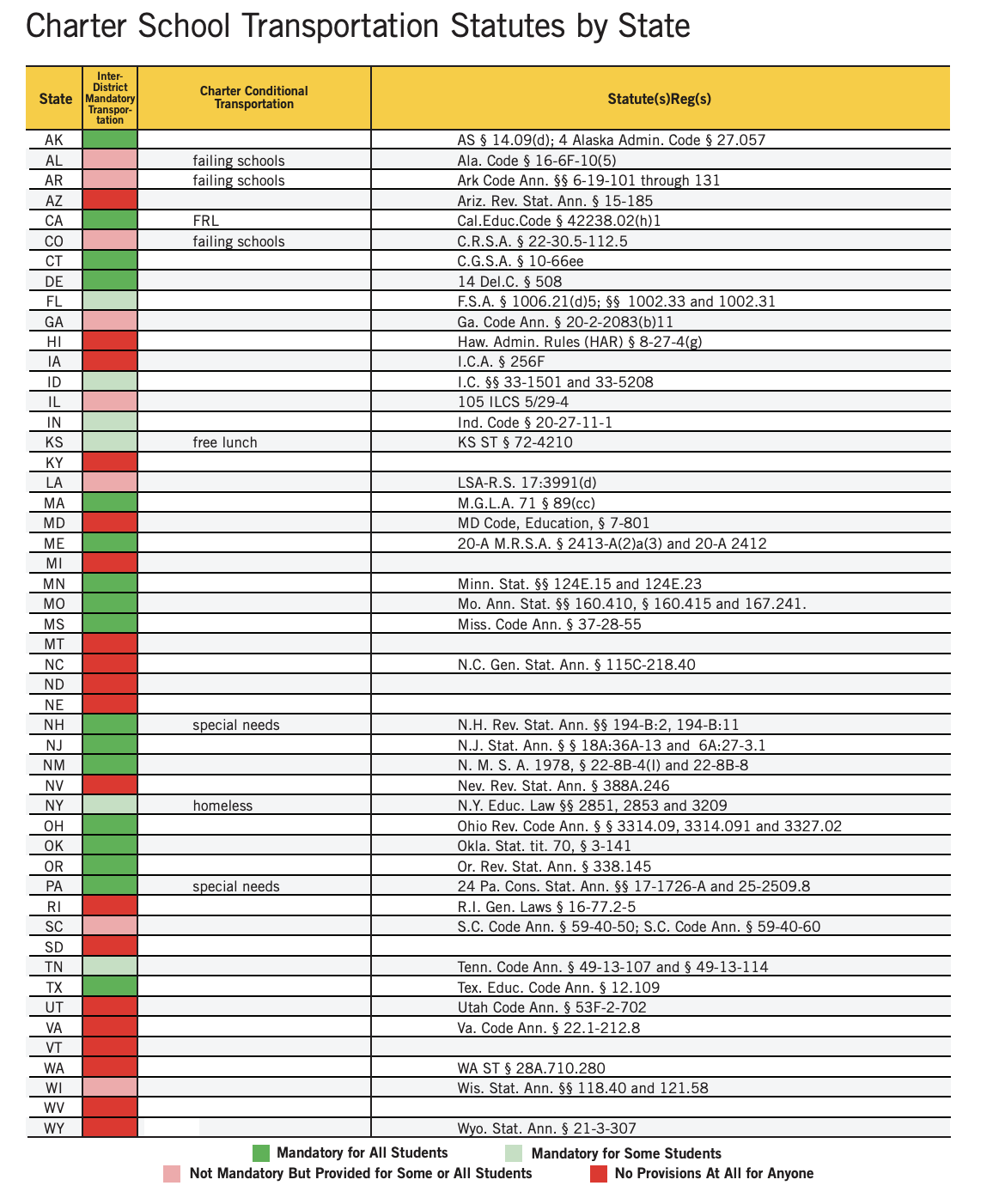

In 31 states, transportation funding or services are made available for charter school students. Figure 2 shows those states. Of those 31 states, 17 mandate some form of transportation funding for charter school students at a level equivalent or roughly equivalent with public district school students. In addition to these charter student transportation policies, states also mandate pupil transportation services for charter school students zoned to “failing” public schools, FRL-eligible students, students with special needs, and homeless students.

As with inter-district choice, the manifestations of these policies vary. In California and Maine, for example, charter schools can receive the same student transportation allotment that traditional public schools receive, but only if they offer transportation services to students. In Indiana, districts are required to provide transportation for charter school students along existing bus routes. In states like Delaware, Massachusetts, and Tennessee, charter schools can work with districts for transportation (with the districts receiving the transportation funding) or can opt to go on their own and receive funding from the state to provide their own transportation services. The full list of state provisions, including the relevant citations to state law are available in Appendix 2.

Private Schools

According to the National Center for Education Statistics, 5.8 million children attended private schools in 2016.29 Unlike other forms of school choice, private schooling is actually on the decline. In 1999, 6.0 million students attended private schools.30 Cost is obviously a factor, as all of the other school choice options we have discussed thus far are tuition-free to families. But transportation plays a role as well. It adds to the costs (in time, money, and effort to coordinate) that families already must bear to send their children to private schools.

Providing transportation to students who attend private schools has a long and controversial history. Two provisions contained in some state constitutions affect the ability of states and district to provide transportation to students attending private schools. As helpfully summarized in the Institute for Justice’s 2016 publication School Choice and State Constitutions, 29 states have “compelled support” clauses in their Constitutions, and 37 states have “Blaine” amendments.31 Compelled support clauses prohibit, as the name suggests, anyone in a state from being compelled to financially support a church or church ministry. They have their origin in colonial times, when people were compelled to attend or financially support a colony’s established church. Blaine Amendments, named after the 19th century politician James G. Blaine, bar public support of religious institutions. Blaine amendments date from a shameful time in American history when anti-Catholic bigotry and anti-immigrant KnowNothingism worked to restrict the freedoms of those who did not conform to the era’s dominant Protestant ideology. At the time they were written, language barring public dollars from being appropriated to “sectarian” institutions (as it is usually formulated) really meant barring public dollars to Catholic institutions, as the publicly funded “common” schools were de facto Protestant schools.

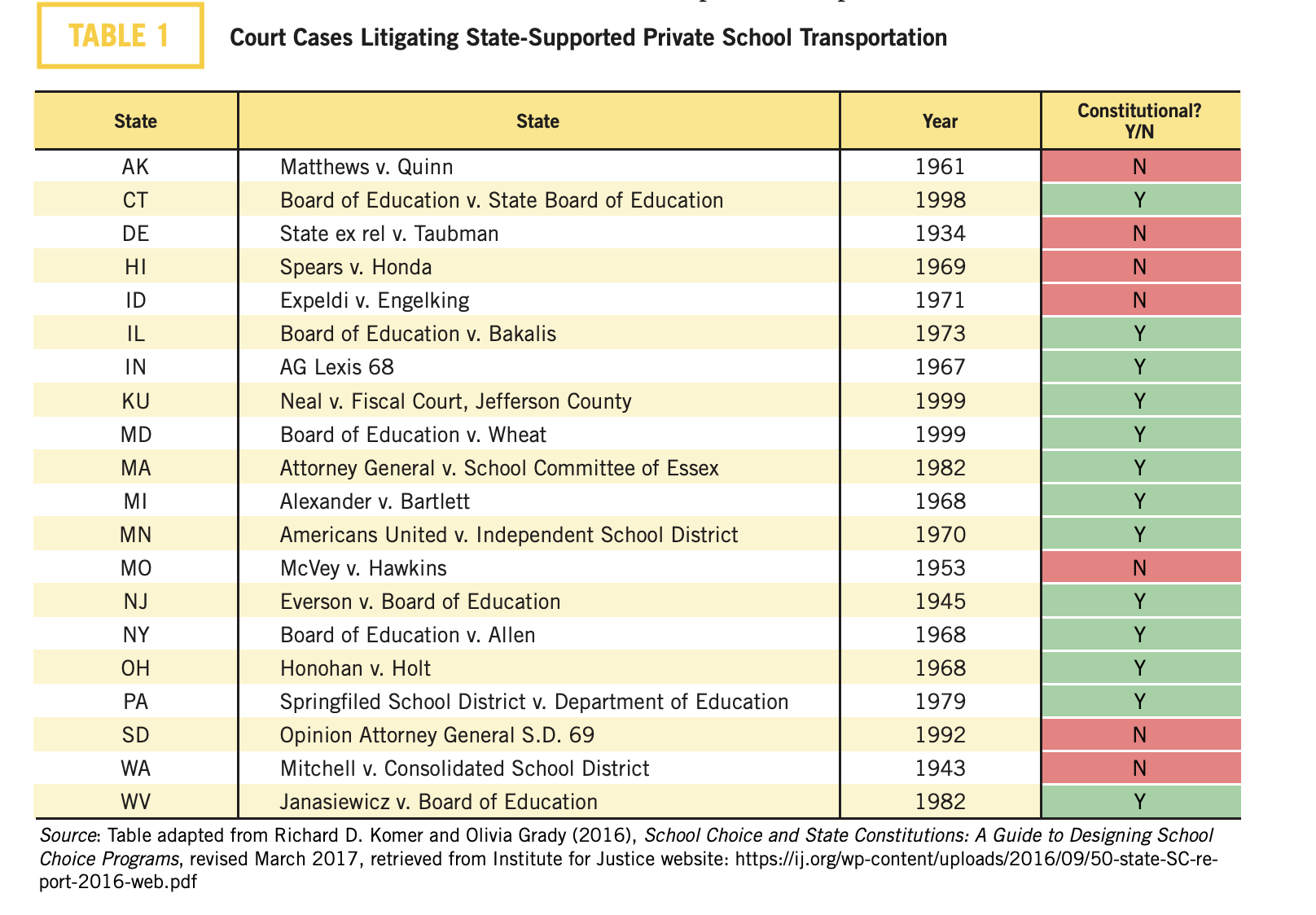

The language in state compelled support clauses and Blaine Amendments vary, as does how various state courts have interpreted them over the years. Numerous different policies, from textbook loan programs to school voucher programs have run into challenges under these provisions. Student transportation policies have as well. Table 1, adapted from the legal analysis in School Choice and State Constitutions, breaks down the cases that have looked at private school pupil transportation over the years.

Of the 20 state cases that have tackled the issue, 13 have found that private school transportation was constitutional, and seven have found that it was not. When found to be constitutional, as in Minnesota’s 1970 Americans United v. Independent School District decision, the court held that support for private schools was incidental and could not be interpreted as either compelling support of a religious organization or directly supporting one. The true beneficiaries were families, not schools. The program was helping kids get to school, whether that school was religious or secular. Children only attended religious schools by the decision of their parents, not the program. Other states, like Illinois, ruled that the program was a health and safety program, and thus was constitutional, and New Jersey ruled that it was helping students comply with compulsory education laws.

Given the different wording of different state Blaine Amendments and compelled support clauses, there is no one answer across the country as to the constitutionality of state support of private school transportation. There is a strong argument that it should not be viewed as support of religious organizations, but that view is not universally shared.

This constitutional jurisprudence affects which states choose to provide support to these school choices.

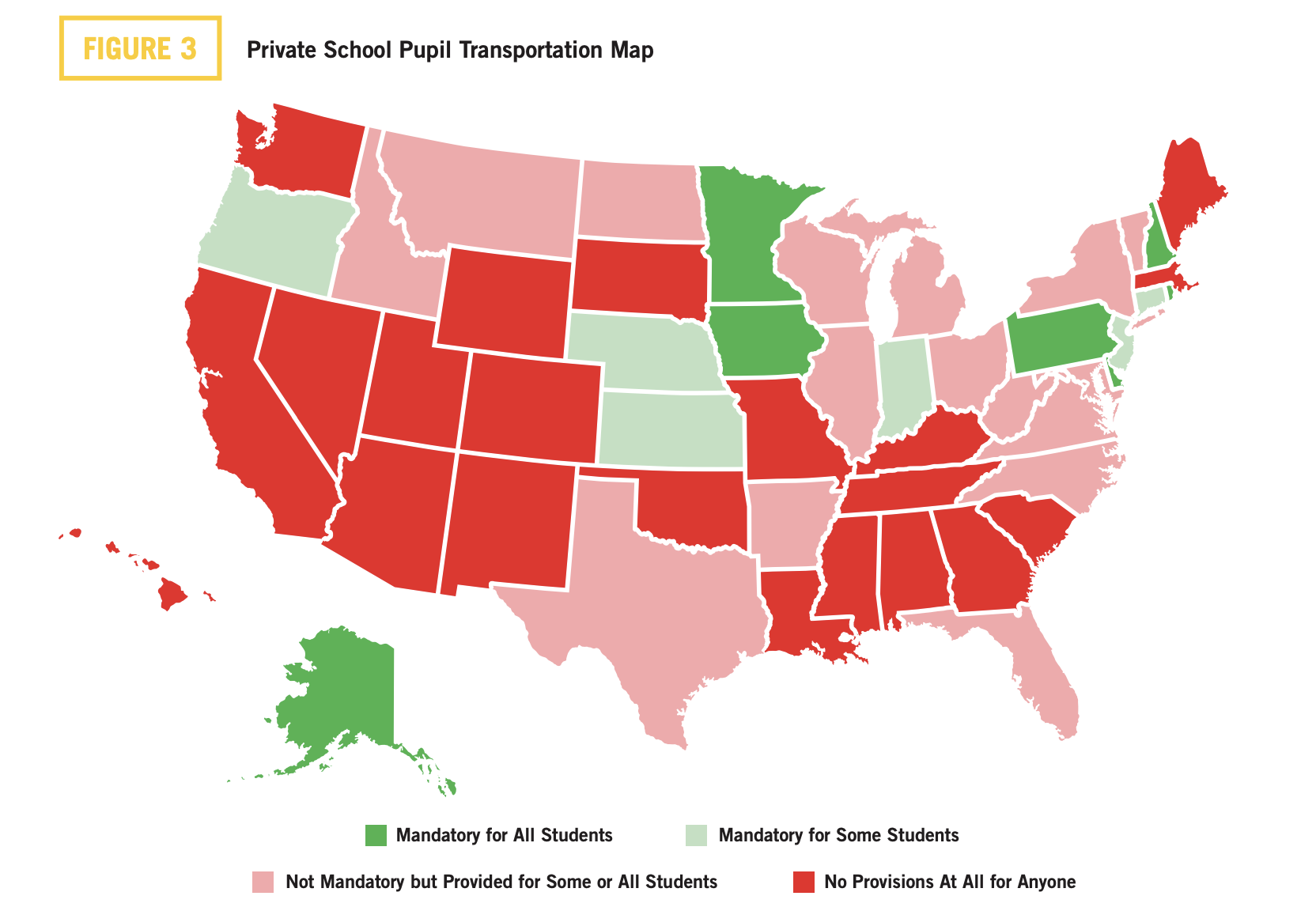

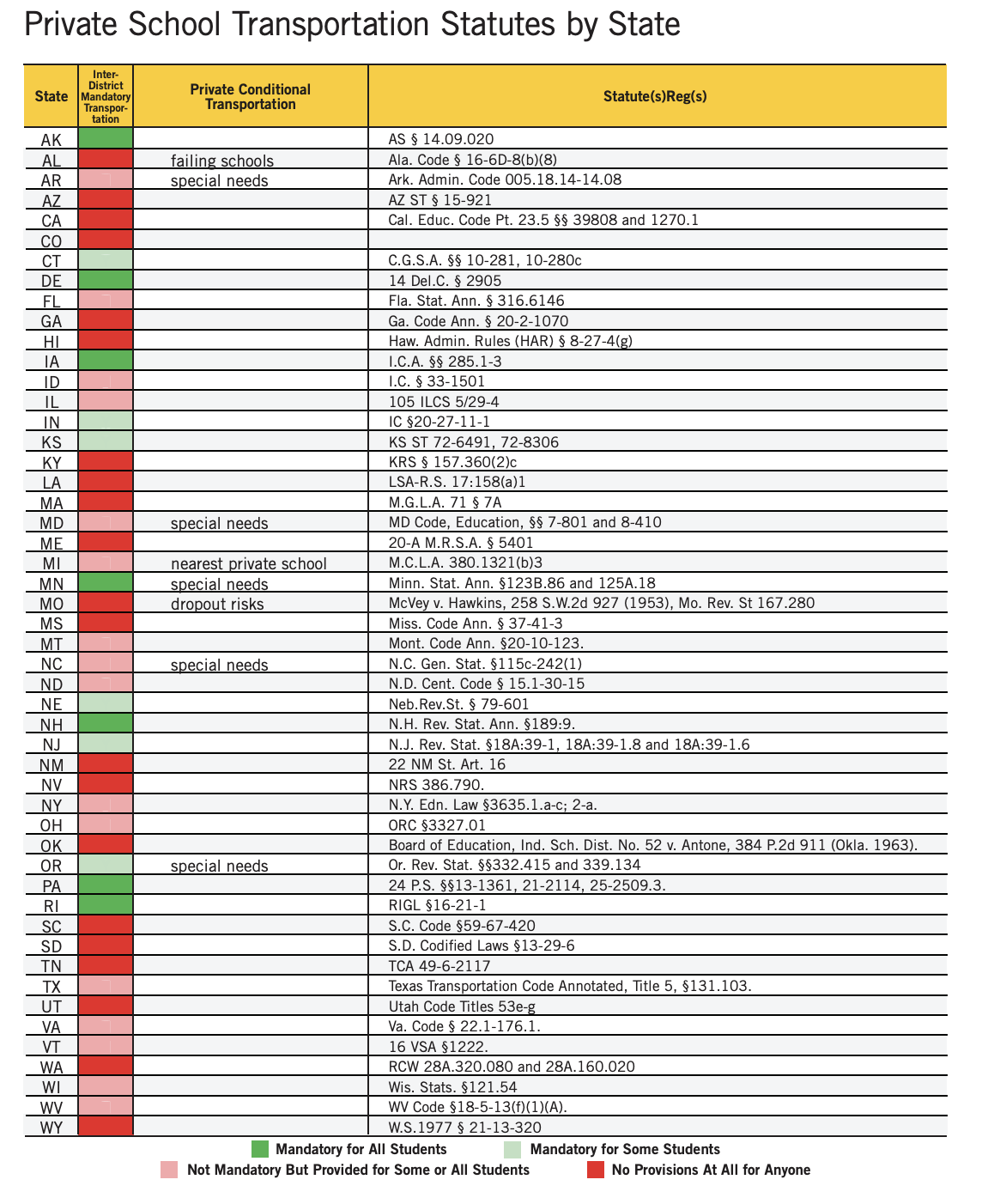

So how many states actually provide transportation for private school students? By statute and/ or regulatory code, 29 states have provisions to provide transportation for private school students. Of those states, seven mandate transportation services or funding at levels equivalent or roughly equivalent to those of public district school students. Populations of private school students also entitled to state or district-provided transportation aid include students with special needs, students zoned to “failing” public schools, students attending the nearest private school to their residence, and students deemed to be at risk of dropping out of school.

But, as with our previous two policy sections, it’s complicated. In states like Connecticut, Delaware, Iowa, and Pennsylvania, private school students are entitled to the same transportation as public school students within their school districts. In Indiana and Oregon, private school students can use buses along established public school bus routes. In Wisconsin and Rhode Island, private school students can use public school buses but with geographic limitations.

State-mandated pupil transportation for private school students is also often limited to students attending non-profit private schools. Connecticut’s law providing transportation for private school students, for example, contains limiting provisions for both within-district private schools as well as nonprofit private schools.32

The full list of state provisions, including the relevant citations to state law are available in Appendix 3.

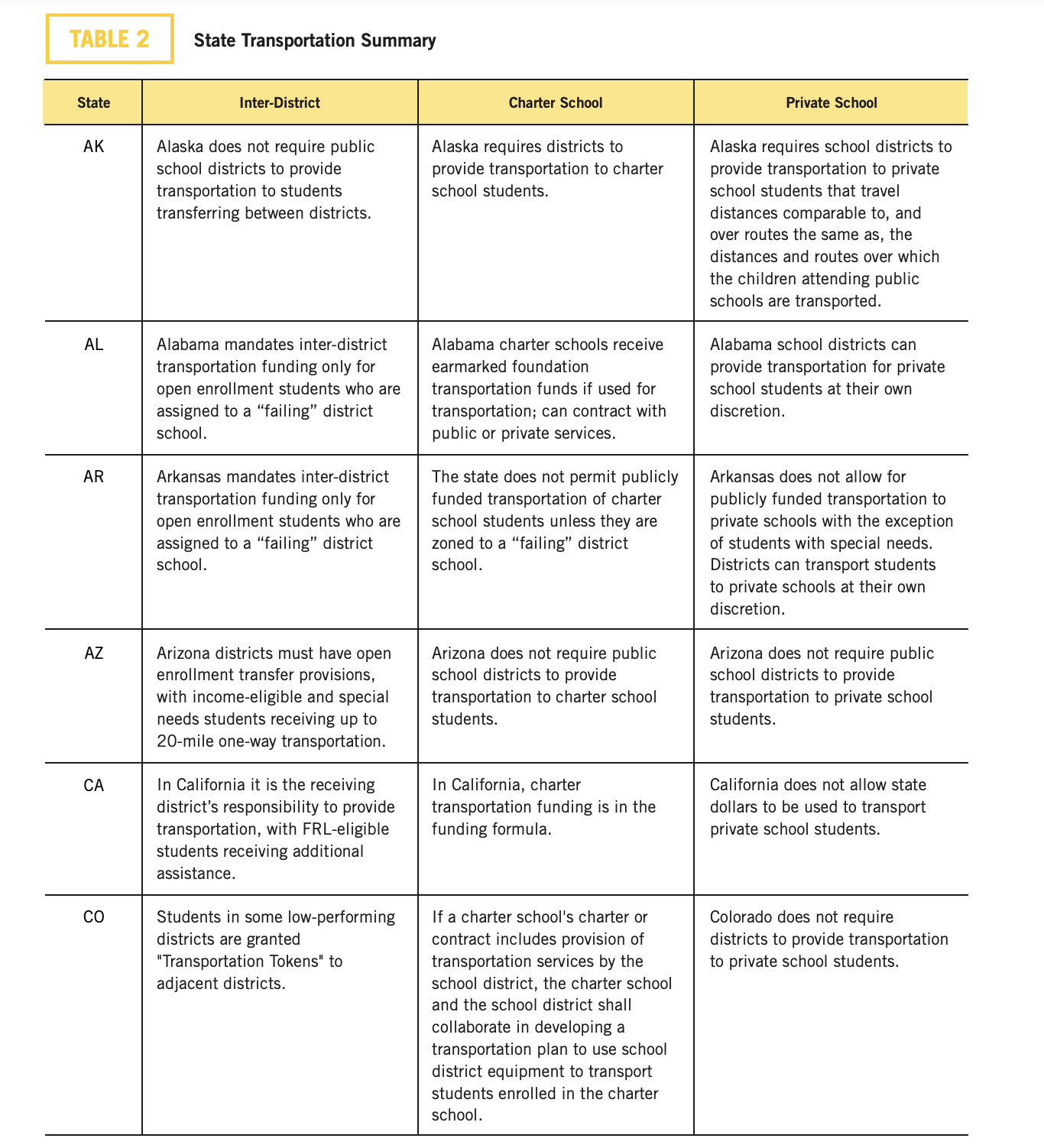

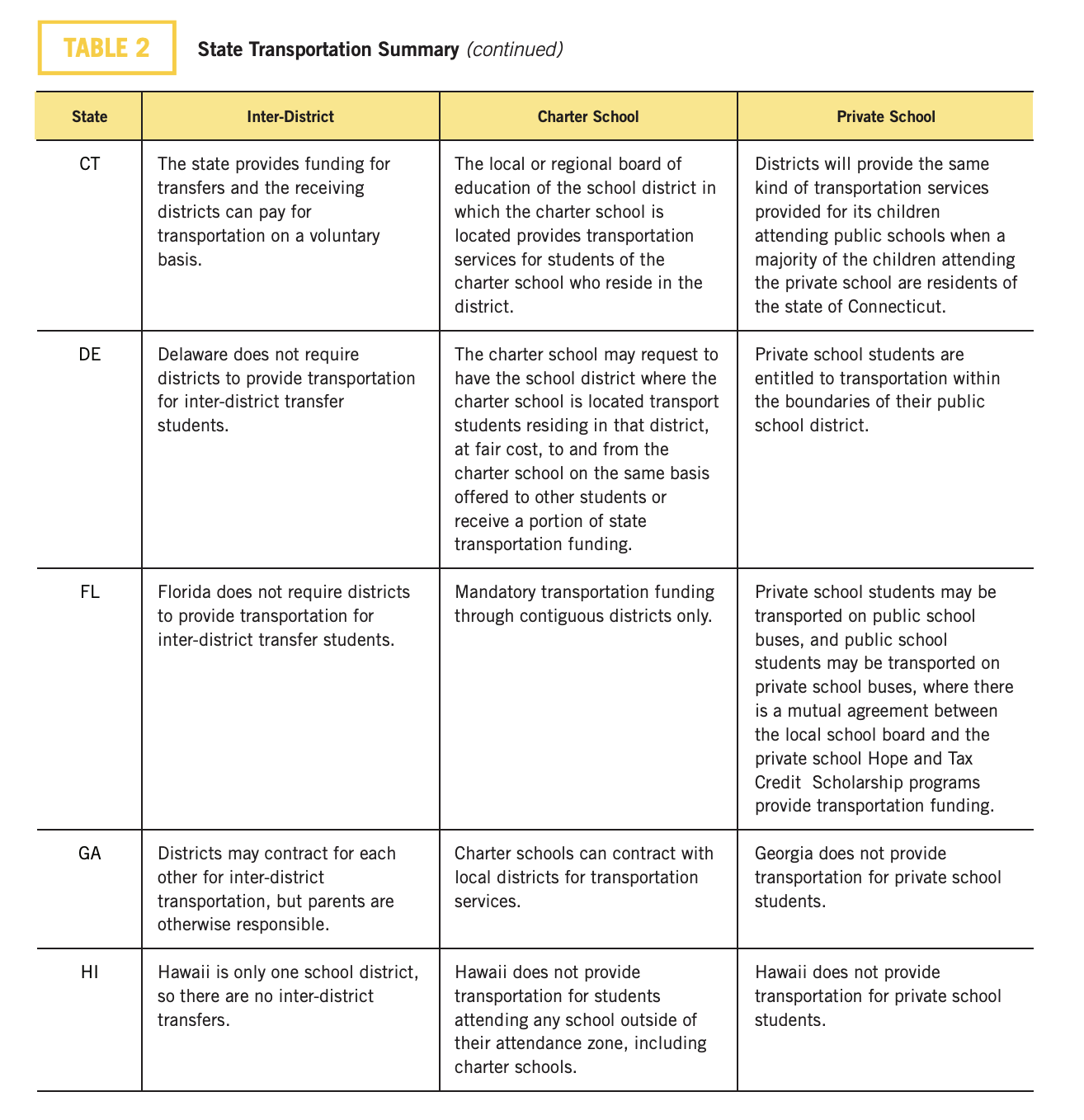

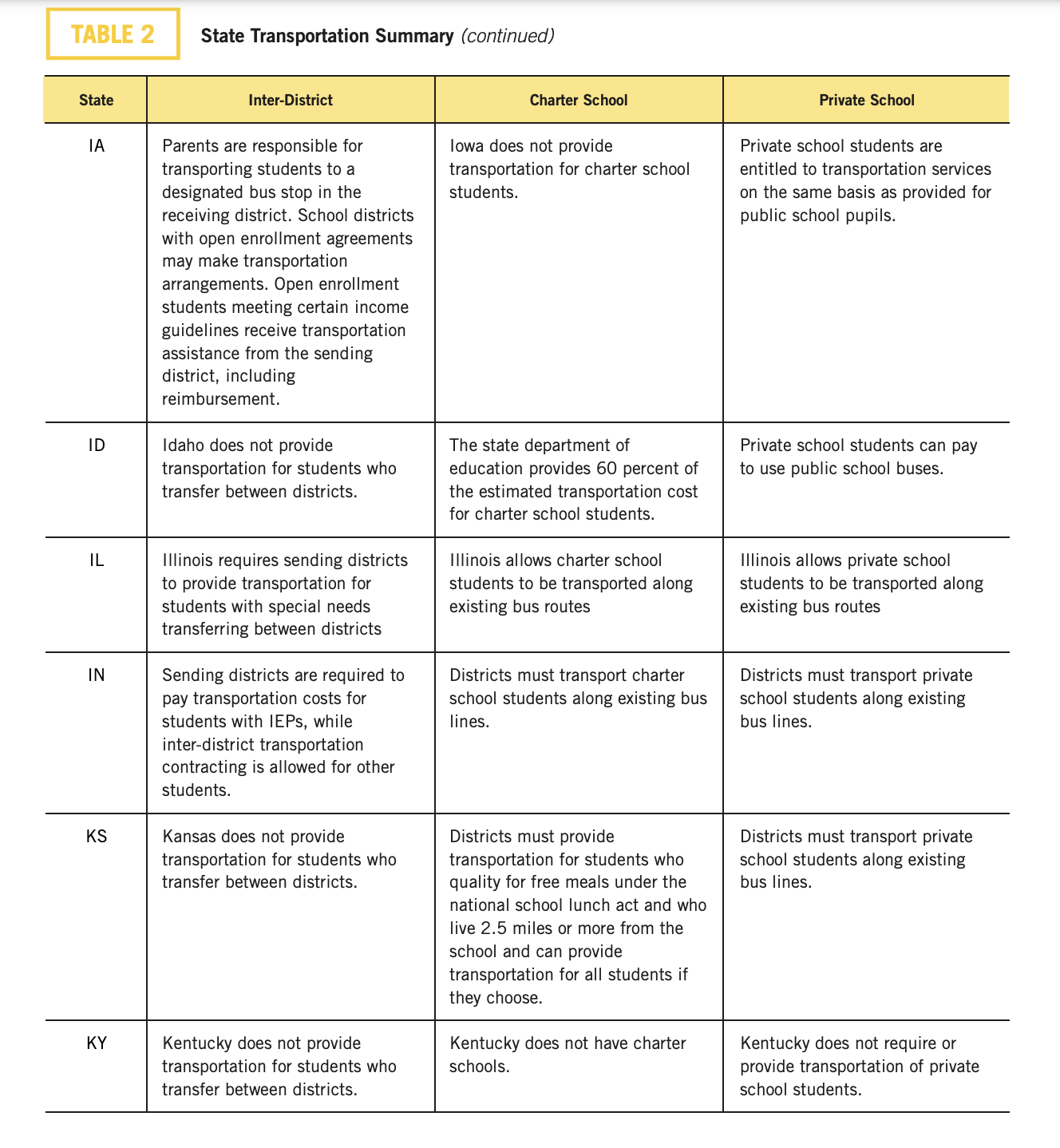

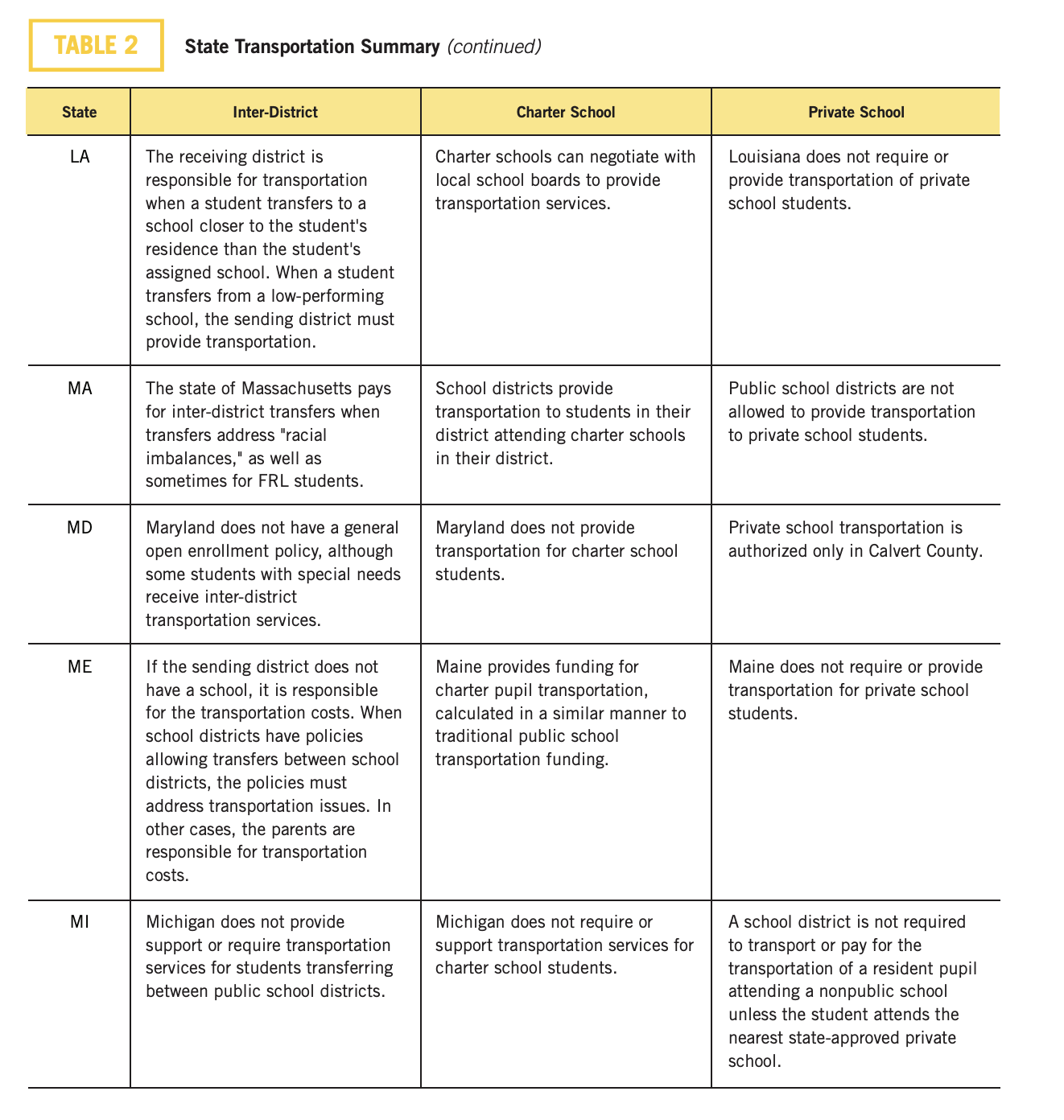

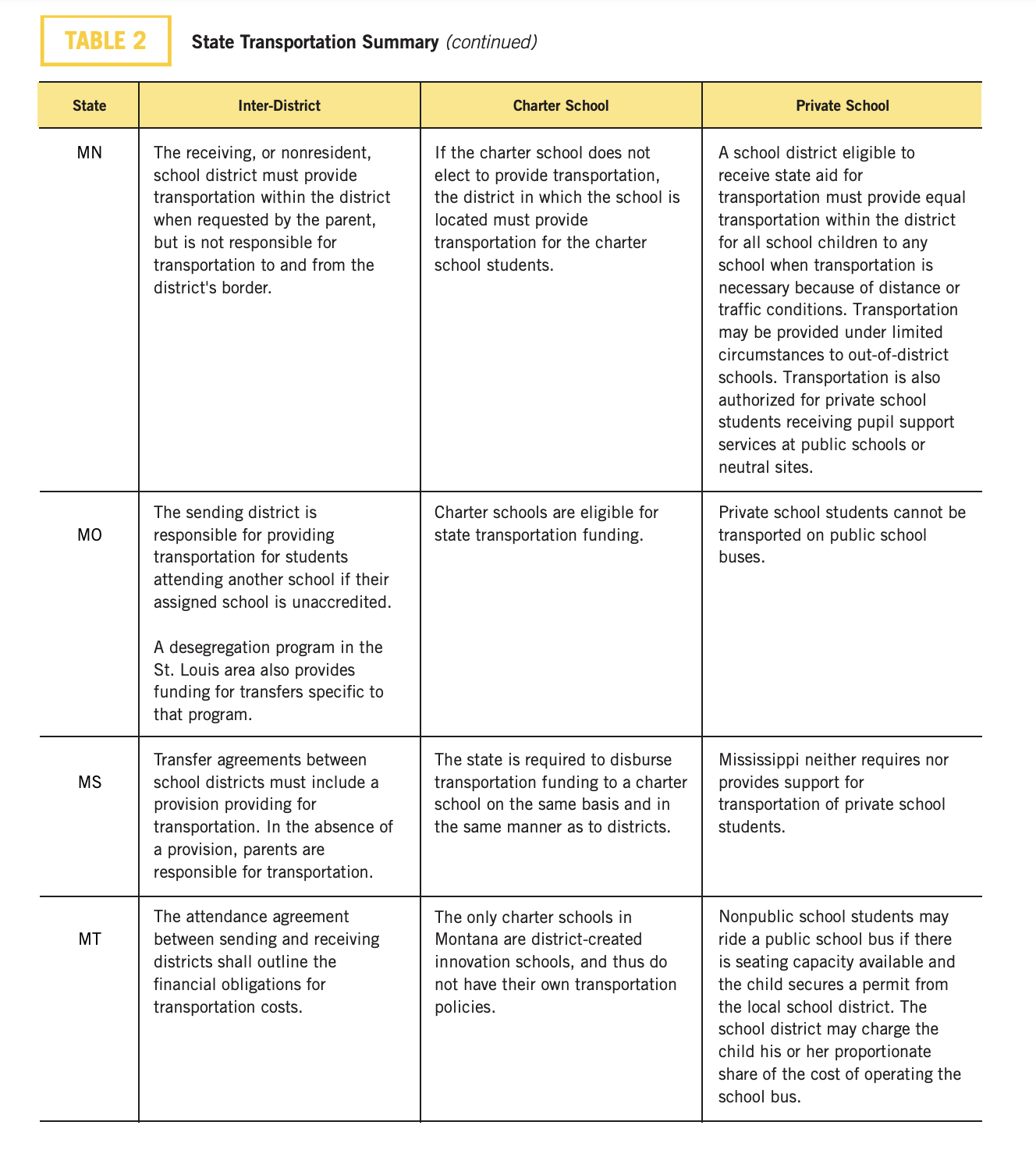

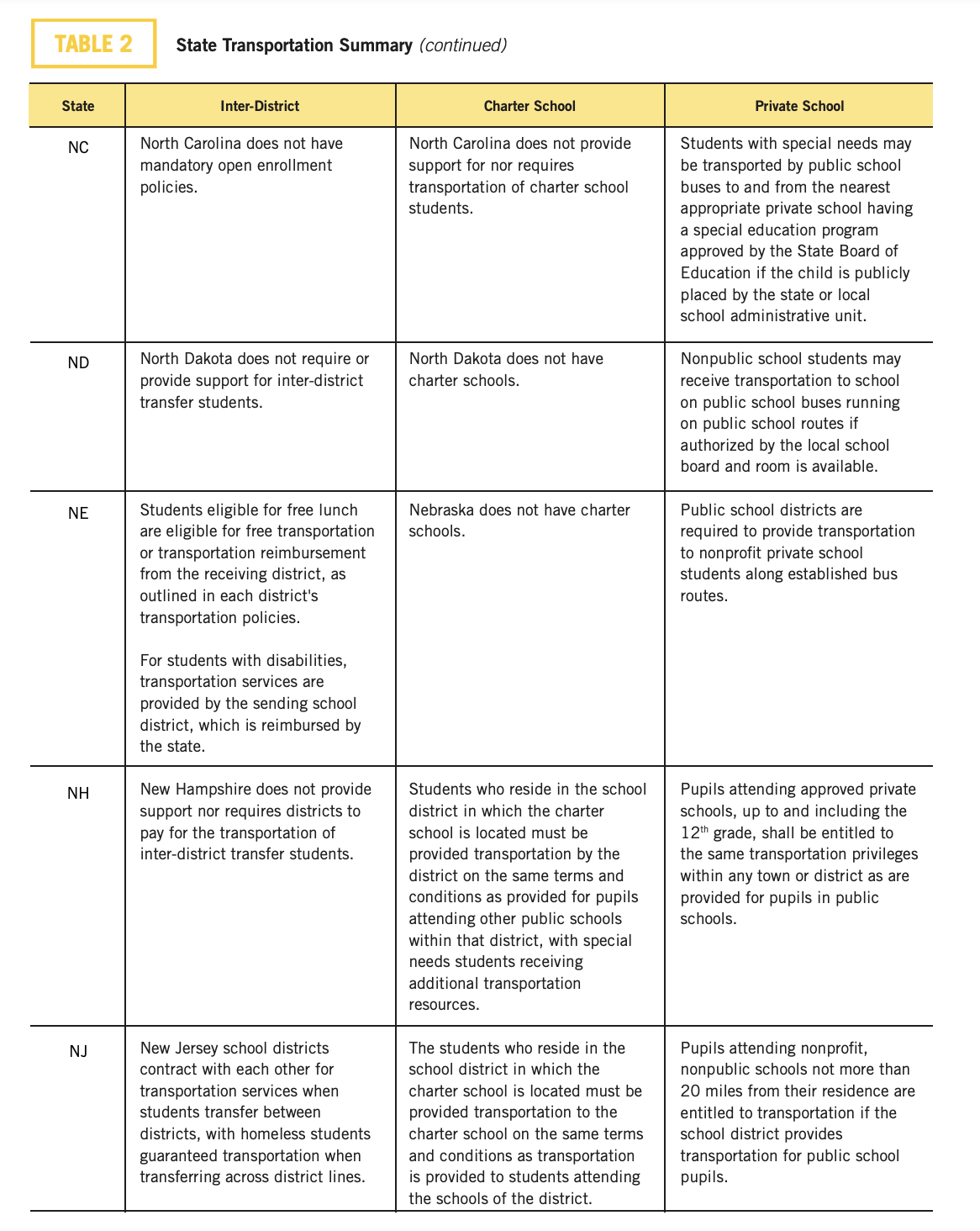

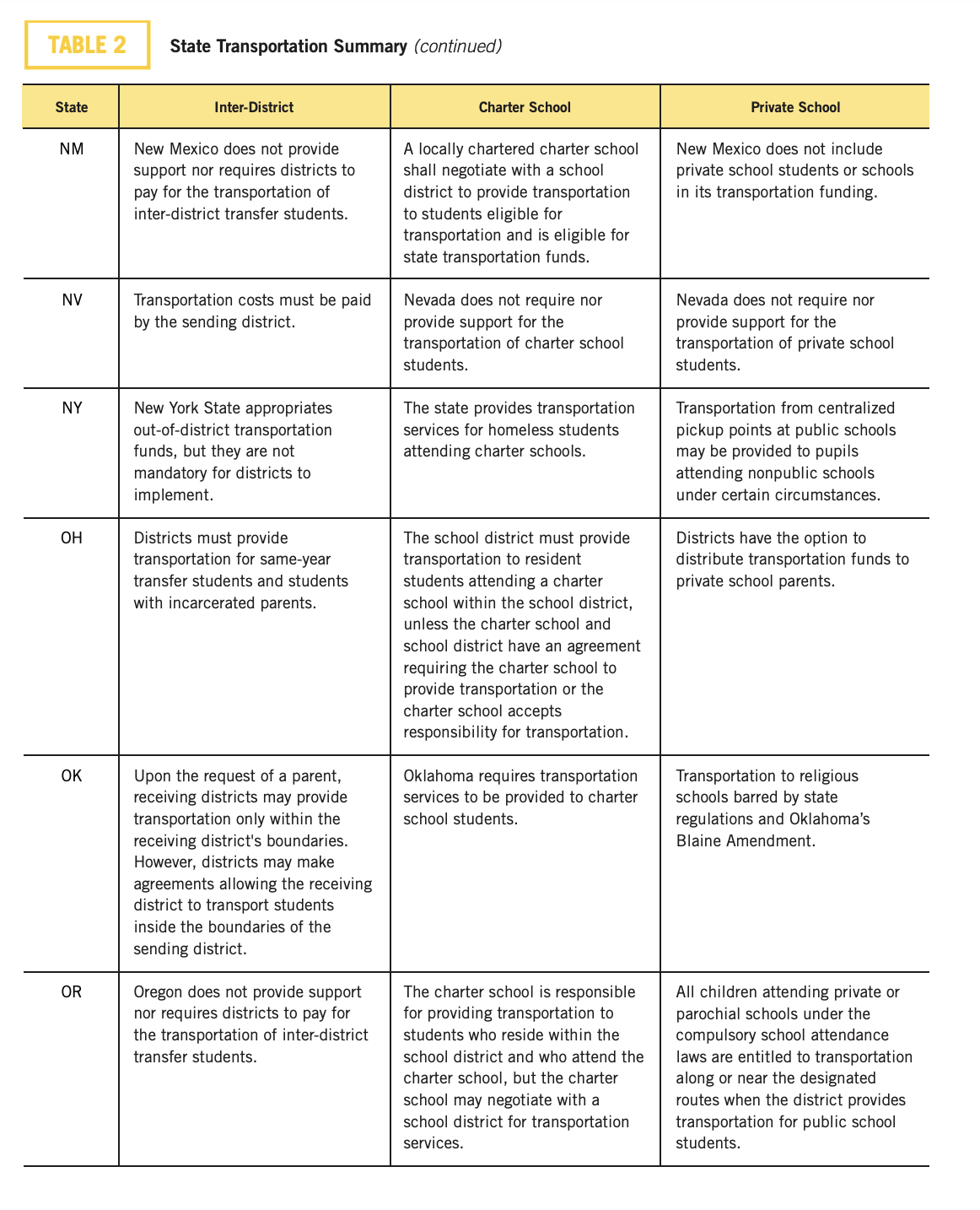

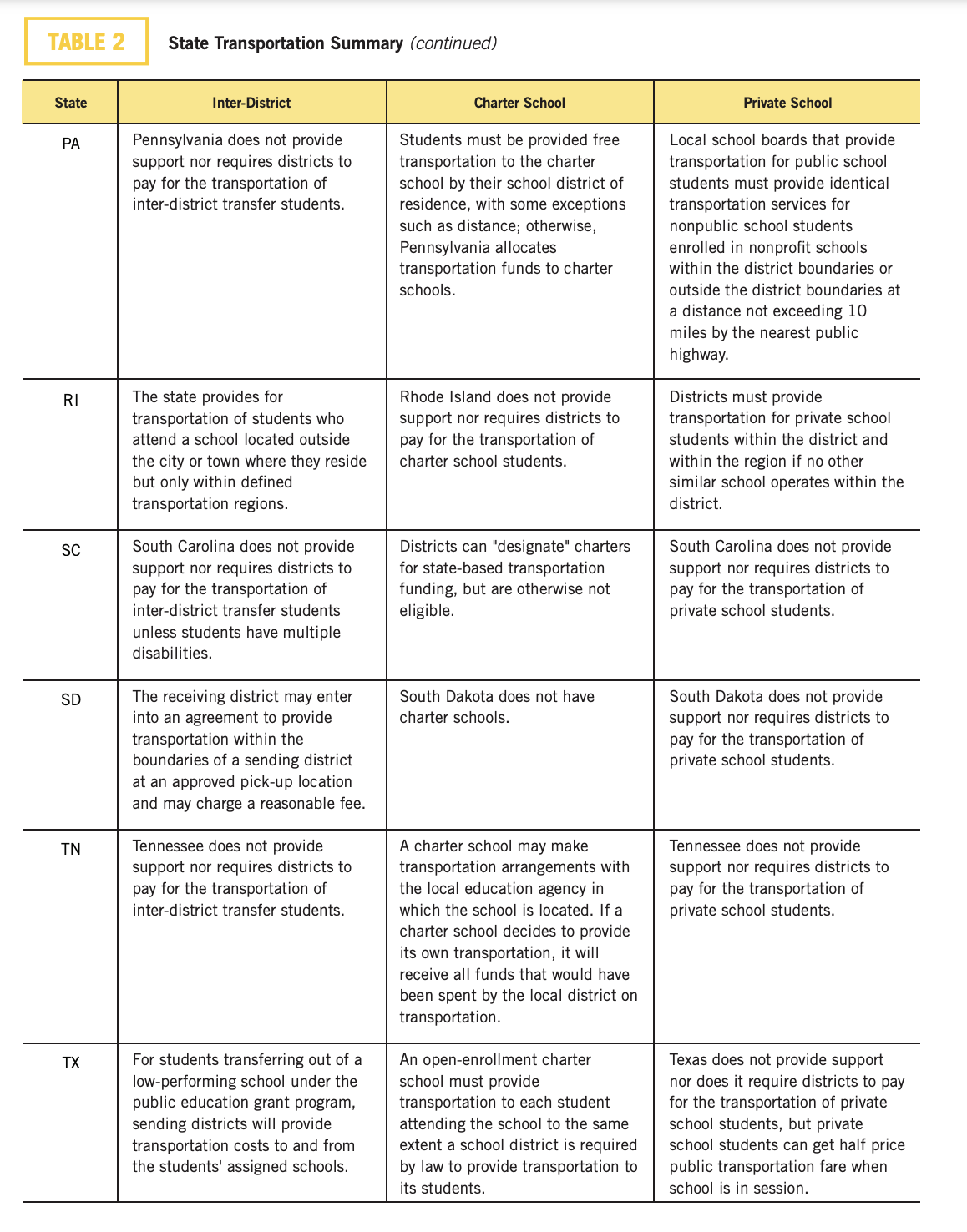

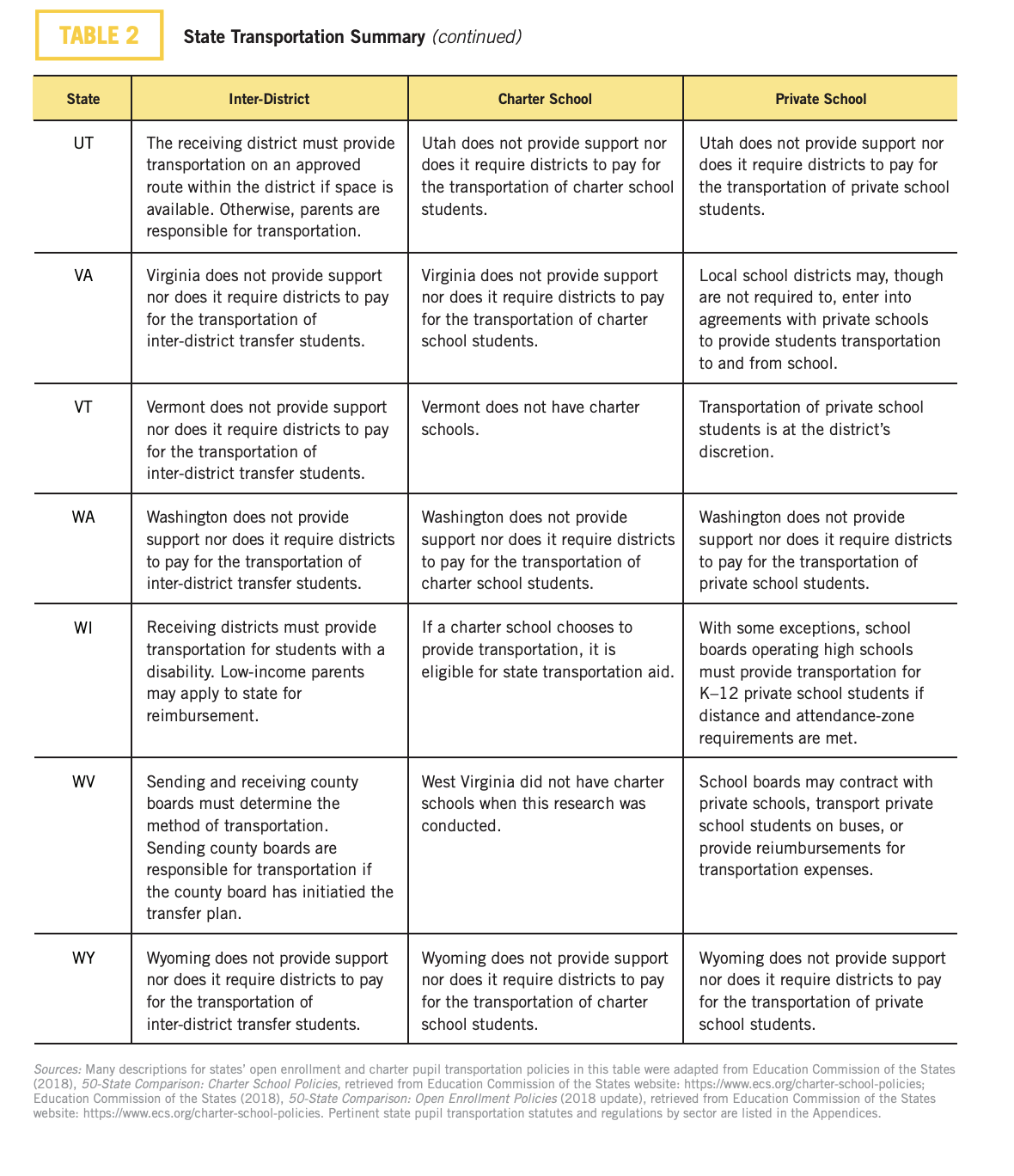

State-By-State Summary

In one word, laws governing the transportation of school choice students are complex. We have done our best to summarize what each state offers (or doesn’t offer) inter-district, charter, and private school families. Appendices 1, 2, and 3 provide the statutes summarized in Table 2.

Conclusion

States and districts across the country are looking to optimize their bus routes to save money and to minimize travel times for students. Bus companies are looking to make buses and bus journeys safer. Choice, both within the traditional public school system and outside of it, is growing. There are enough points of frustration to push for change.

Technology can help, but mindsets must change first. More and more children are opting out of their traditional, residentially assigned school, and forward-thinking states need to recognize that their pupil transportation systems are going to have to adapt to this new reality. This provides a great opportunity to improve racial and socio-economic integration, match students to learning environments that better meet their needs, and create a system that is more flexible, more pluralistic, and more personalized. We should support this, and those involved in pupil transportation should see the positive role that they can play in advancing these trends. Once we recognize the large role that pupil transportation can play, we can start to leverage it.

Private school choice programs have not, to date, been helpful in overcoming transportation barriers. Though for a time the Florida Tax Credit Scholarship Program provided pupil transportation funding, today only two education savings account (ESA) programs (in Mississippi and North Carolina) allow ESA dollars to be used for pupil transportation. Nevada’s shortlived program allowed for up to $750 to be used for transportation, but it went away with the dissolution of that program.

Policy Recommendations

We’d like to offer a set of policy recommendations based on our review of the literature on pupil transportation and school choice and our examination of the current legal landscape.

States should appropriate funding for charter schools to transport their students to their schools.

Charter school students need to be able to get to school just like every other child does. In many states, if charter schools want to provide transportation, they have to dig into the general funding that they receive from the state. They do not get dedicated pupil transportation funding. This should change. They should get the same transportation allotment as traditional public schools. Now, charter schools will have to be creative with this funding, as more than likely their students will have to travel greater distances and be more dispersed than residentially assigned traditional public school students, but that is a fair tradeoff for access to state transportation funding.

Private school choice programs should allow pupil transportation as an allowable use of ESA, tax-credit scholarship, or voucher dollars.

If schools or families want to partner with the local district to share these funds to help defray the costs of transporting students on existing buses, great. If they want to buy and operate their own buses or use some other form of transportation (like ridesharing), that is great too. They will know what the best way to transport their students is. This might mean increasing the amount of money available in the voucher, tax-credit scholarship, or education savings account to take into account that a portion will be used for transportation.

States should not artificially restrict pupil transportation methods.

According to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, school buses are “the most regulated vehicles on the road.”33 While protecting students safety is the highest priority, human transportation is evolving. Ridesharing apps and, more distantly in the future, autonomous vehicles have and will continue to change how we move around. States should be careful when they regulate buses or place requirements on the types of vehicles that can transport students so that they do not inadvertently prevent innovation. There are many safe options to transfer pupils that are not big yellow school buses, and these options might solve problems that schools have.

Schools and districts should look to technological solutions to improve their transportation systems to drive down costs and allow more students to participate.

If cost is a barrier to providing transportation services for children to attend schools outside of the traditional school district, then driving down the cost of pupil transportation should be a top priority. Startups like Kansas City’s Transportant are working on technological solutions to gather better data on bus routes and optimize them in a variety of ways, but there is much work to be done.

Policymakers should look to improve the quality of the current pupil transportation system.

It is important that facilitating school choice does not come at the expense of an overburdened pupil transportation system. Existing systems can still have children on buses for long periods of time at high cost. Improving how buses are routed and how the web of school options can be navigated is a huge opportunity for technological solutions and those in the school choice movement should work to support such innovation.

School choice supporters neglect the role of pupil transportation at their peril. Provisions for student transportation should be incorporated in policies attempting to advance school choice. Leaving the means to get to a school of choice out of the equation risks creating choice in name only.

Appendix 1

Appendix 2

Appendix 3

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Juliet Squire of Bellwether Education Partners, Christopher Ruszkowski of the Hoover Institution, and Olivia Grady of Americans for Tax Reform for reviewing drafts of this paper. Our EdChoice colleagues Jason Bedrick, Paul DiPerna, and Marty Lueken also reviewed an early draft. We would like to thank Katie Brooks from EdChoice for editing and Michael Davey of EdChoice for layout. We owe a particular debt of gratitude to the Education Commission of the States online 50-State Comparison of charter and open enrollment policies. It proved to be an invaluable starting point and reference throughout the project. All errors are the authors’ and the authors’ alone.

Endnotes

- Matthew M. Chingos and Kristin Blagg (2017), Who Could Benefit from School Choice? Mapping Access to Public and Private Schools? (Evidence Speaks Reports Vol 2, #12), retrieved from Brookings Institution website: https://www.brookings.edu/research/who-could-benefit-from-school-choice-mapping-access-to-public-and-private-schools

- Paul Teske, Jody Fitzpatrick, and Tracey O’Brien (2009), Drivers of Choice: Parents, Transportation, and School Choice, retrieved from Center for Reinventing Public Educaiton website: https://www.crpe.org/sites/default/files/pub_dscr_teske_jul09_0.pdf

- Id. at 22-23

- Urban Institute (2017), Student Transportation and Educational Access Working Group, Student Transportation and Educational Access, retrieved from https://www.urban.org/policy-centers/cross-center-initiatives/education-policy-program/projects/student-transportation-and-educational-access

- Phillip Burgoyne-Allen, Katrina Boone, Juliet Squire, and Jennifer O’Neal Schiess (2019), The Challenges and Opportunities in School Transportation Today,Slide 9, retrieved from Bellwether Education Partners website: https://bellwethereducation.org/publication/challenges-and-opportunities-school-transportation-today

- National Center for Education Statistics, Fast Facts: Transportation [Web page], retrieved from https://nces.ed.gov/fastfacts/display.asp?id=67

- Carolyn Sattin-Bajaj (2018), It’s Hard to Separate Choice from Transportation: Perspectives on Student Transportation Policy from Three Choice-Rich Districts, retreived from Urban Institute website: https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/99246/school_transportation_policy_in_practice.pdf

- Andrew D. Catt and Michael Shaw (2018), Indiana’s Schooling Deserts: Identifying Hoosier Communities Lacking Highly Rated Schools, Multi-Sector Options, retrieved from EdChoice website: https://www.edchoice.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/Indianas-Schooling-Deserts-by-Andrew-Catt-and-Michael-Shaw.pdf

- Andrew D. Catt and Michael Shaw (2019) Rural communities Lacking Multi-Sector Schooling Options: Indiana’s School Choice Deserts. “Journal of School Choice, 13(4) pp.576-598, dx.doi.org/10.1080/15582159.2019.1691850

- Paul DiPerna and Michal Shaw (2018), 2018 Schooling in America Survey, p. 17, retrieved from EdChoie website: https://www.edchoice.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/2018-12-Schooling-In-America-by-Paul-DiPerna-and-Michael-Shaw.pdf; EdChoice (2018), Questionnaire, Results, and Additional Data: 2018 Schooling in America Survey, p. 9, retrieved from EdChoice website: https://www.edchoice.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/SIA-Questionnaire-and-Toplines.pdf

- EdChoice (2017), Questionnaire and Topline Results: Why Indiana Parents Choose, Q57, p. 22, retrieved from https://www. edchoice.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/Why-IndianaParents-Choose-Questionnaire-and-Topline-Results.pdf

- Jason Bedrick and Lindsey Burke (2018), Surveying Florida Scholarship Families: Eperiences and Satisfaction with Florida’s Tax-Credit Scholarship Program, p. 2, retrieved from EdChoice website: https://www.edchoice.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/2018-10-Surveying-Florida-Scholarship-Families-byJason-Bedrick-and-Lindsey-Burke.pdf

- Patrick Denice and Betheny Gross (2018, Going the Distance: Understanding the Benefis of a Long Commute to School, retrieved from Urban Institute website: https://www.urban.org/research/publication/going-distance-understand-benefits-long-commute-school

- “School quality” was defined as higher rates of school-level proficiency on state English language arts and math exams

- Sarah A. Cordes and Amy Ellen Schwartz (2018), Does Pupil Transportation Close the School Quality Gap?, retrieved from Urban Institute website: https://www.urban.org/research/publication/does-pupil-transportation-close-school-quality-gap

- Betheny Gross (2019), Going the Extra Mile for School Choice: How Five Cities Tackle the Challenge of Stuent Transportation, Education Next, 19(4), retrieved from https://www.educationnext.org/going-extra-mile-school-choice-how-five-cities-tackle-challenges-student-transportation

- Two resources were instrumental in providing a starting point as well as a verification backstop for this research. The U.S. Department of Education’s Office of Non-Public Education collects and reports states’ regulations pertaining to private schools, although there is a moderate degree of variation in how recently various states’ regulations have been updated by the office. See: U.S. Department of Education, State Regulations of Private and Home Schools [Web page], last modified September 5, 2019, retrieved from https://www2.ed.gov/about/inits/ed/non-public-education/regulation-map/index.html In addition, the Education Commission of the States released both charter school and open enrollment 50-state policy comparisons in 2018. These comparisons provided insightful analyses related to states’ transportation policies within these schooling sectors. See Education Commission of the States (2018), 50-State Comparison: Charter School Policies, retrieved from Education Commission of the States website: https://www.ecs.org/charter-school-policies; Education Commission of the States (2018), 50-State Comparison: Open Enrollment Policies (2018 update), retrieved from Education Commission of the States website: https://www.ecs.org/charter-school-policies

- Terms for private school choice included “private,” “private school,” “nonpublic,” and “non-public.” Terms for open enrollment included “legal settlement,” “residence,” “resides,” “school corporation,” “transfer,” “outside and district,” “open enrollment,” “non-resdient,” “inter-district,” and “intra-district.” Terms for charter schools included “charter,” “community school”, and ”authorize/d.” Transportation-related terms included “transport,”“transportation,” “bus,” and “busing.”

- We should note that our baseline of comparison is traditional public schools and students; students attending alternative public schools were not accessed for the sake of comparison as laws pertaining to such schools generally have more liberal pupil transportation policies.

- For those interested in an overview of pupil transportation policy and practice in general, we would recommend The Challenges and Opportunities in School Transportation Today, retrieved from Bellwether Education Partners website: https://bellwethereducation.org/publication/challenges-and-opportunities-school-transportation-today

- James Sibley (2019, April 8), Don’t Be an IEP Afterthought – Transportation is More Than a ‘Related Service’, School Transportation News, retrieved from https://stnonline.com/blogs/dont-be-an-iep-afterthought-transportation-as-more-than-just-a-related-service

- Arizona, for instance, requires districts to report routes, vehicle inventory, maintence, and daily route mileage, among other variables. See Arizona Department of Education (2014), Policies & Procedures Manual: Transportation Guideline, retrieved from https://www.azed.gov/finance/files/2014/06/sf-0002-transportation-guideline-issued-7-1-14.pdf

- New York City’s Department of Education, for instance, distributes MetroCards to students living more than half of a mile from their school. See New York City Department of Education, Metrocards [Web page], accessed October 15, 2019, retrieved from https://www.schools.nyc.gov/school-life/transportation/metro-cards

- We encourage curious readers to read the cited statutes and regulations in order to better appreciate these nuances that could not be adequately captured in a policy landscape paper such as this.

- For a complete list of states offering open enrollment, see Education Comission of the States, 50-State Comparison: Does the State Have Open Enrollment Programs? [Web page], last modified October 2018, retrieved fromhttp://ecs.force.com/mbdata/MBQuestNB2n?rep=OE1801

- Ke Wang, Amy Rathbun, and Lauren Masu (2019), School Choie in the United States: 2019 (NCES 2019-106), retrieved from https://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch/pubsinfo.asp?pubid=2019106

- 105 ILCS 5/27A-7

- It is worth noting, too, that many urban charter schools share with and lease facilities from school districts. This may make it easier for such district-charter transportation coordination that several states mandate. On the other hand, for charter schools that have difficulties in securing facilities, the placement of schools in less-desirable and further-removed areas may exacerbate transportation difficulties – especially in states where district-supported charter student transportation is only manded along preexisting district bus routes.

- Ke Wang, Amy Rathbun, and Lauren Masu (2019), School Choie in the United States: 2019

- Id.

- Richard D. Komer and Olivia Grady (2016), School Choice and State Constitutions: A Guide to Designing School Choice Programs, revised March 2017, retrieved from Institute for Justice website: https://ij.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/50-state-SC-report-2016-web.pdf

- Conn. Gen. Stat. § 10-281

- National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, School Bus Safety: School Bus Regulations [Web page], accessed October 15, 2019, retrieved from https://www.nhtsa.gov/road-safety/school-bus-safety#bus-regs