The Unbundling Series: Five Services Public Education Should Do Differently

The greatest superpower the world has ever known laid low by a pandemic, driving divisions that eventually lead to its downfall. Sound worrying?

No, we’re not talking about America, we’re talking about Ancient Rome.

In the year 165 AD, a plague (probably smallpox) began to ravage the Roman Empire, killing roughly 20 percent of the population over the next 15 years and throwing the Roman economy and society into a tailspin. As Kyle Harper argues in his fantastic book The Fate of Rome: Climate, Disease, and the End of an Empire, it was this and subsequent plagues coupled with changing climatic conditions that exacerbated the fissures in the leadership of Rome and eventually led to its downfall.

The later Roman Empire had a problem: The Emperor. There could be only one, and the rules for succession were unclear. When an emperor would die, power struggles would emerge, particularly amongst the powerful generals of the Roman Legions. (This is how the year 193 became the Year of Five Emperors.) As Roman emperors centralized power at the same time they created leadership challenges, the Empire proved less able to deal with crises, from invading barbarians to pandemics to droughts.

There is a lesson here. Centralized power creates a small number of points of failure. If, in a crisis, these key cogs in the machine don’t do their jobs the way they are supposed to, everyone suffers. Centralized power also has less reason to innovate, improve, and push for efficiency. If there is no competing option, they will just keep on keepin’ on.

We’ve seen this in education in the time of COVID-19.

The Center for Reinventing Public Education has been tracking 82 large school districts and found that, as of the end of May:

“27 of them (33 percent), serving hundreds of thousands of students in some of America’s largest cities, still do not set consistent expectations for teachers to provide meaningful remote instruction. And 13 of those 27 additionally do not require teachers to give feedback on student work.”

So what happens if you are a student in one of those 13 districts? Clark County, Nevada, for example, is the sixth largest school district in America and has not expected teachers to provide instruction. Tens of thousands of children are missing months of education because of a centralized decision made by district leadership.

Students in a dozen other districts are in the same boat. Many lack any other options, and the district knows that they have nowhere else to go. They have to take what the district is (or in this case isn’t) giving them. And, this problem is present throughout America’s public education system, including suburban and rural districts.

The way to fix this is to decentralize—to borrow from the lingo of the day, to “unbundle” educational services and providers to create a more diffuse and thus resilient system of education. It will also encourage education providers to better match their products to the needs of children, as families and schools have more options for goods and services. It can drive innovation and create new options that better meet the individual needs of children, families, and schools.

What are some services that could be unbundled?

At the top of the list, we have transportation, food service and professional development. As we will see in the subsequent posts in this series, in all three of those areas, schools, parents and educators are disappointed in what is provided to them for what they pay. Students, families, and teachers are unhappy as well. Perhaps by separating these functions from the school, we can find external operators that can do a better job.

This could take the form of professional development vouchers, as argued by Michael Horn and Mike Goldstein. In a 2015 report, TNTP found “no evidence that any particular kind or amount of professional development consistently helps teachers improve.” This, despite billions of dollars spent each year and millions of hours burned by teachers who could be doing something more useful. Perhaps rather than have the school decide what professional development is provided, teachers can take the money to find the professional development opportunities that best meet their needs.

Food service seems ripe for unbundling as well. Food waste is a serious problem. The guidelines that the federal government promulgates leads food manufactures to re-engineer foods to meet nutritional standards, but in doing so, makes them disgusting. As the New York Times argues in an article titled Why Students Hate School Lunch wrote:

“Consider that in France, where the childhood obesity rate is the lowest in the Western world, a typical four-course school lunch (cucumber salad with vinaigrette, salmon lasagna with spinach, fondue with baguette for dipping and fruit compote for dessert) would probably not pass muster under the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act, because of the refined grains, fat, salt and calories. Nor would the weekly piece of dark chocolate cake.”

Centralized regulation and administration wastes food, keeps kids hungry and frustrates educators who have to try to teach restless children. Can we figure out a better way?

Transportation is one of the toughest nuts to crack. Trying to get students to and from school safely requires a huge amount of infrastructure and manpower willing to work odd hours for low pay. Buses go missing. Kids miss the bus and are stranded. Districts struggle to recruit drivers. It’s a mess. That said, an enormous amount of money is spent on pupil transportation. Knowing that is out there as a reward for a thoughtful entrepreneur who can solve this vexing problem could lead to innovations that can help all parties involved.

But what about more core academic functions? Those could potentially be unbundled as well.

At least a dozen states offer some kind of “course access” program that gives flexibility to public school students to take classes from outside providers. If a school district’s math program stops at Algebra II, for example, but a student is ready for precalculus, he or she might head to the library and take the class online from the state university while his or her classmates are in their traditional classroom. This can work for career and technical education as well, with funding provided for students to go to community or technical colleges or union apprenticeship programs to learn job skills.

Even further down the road are homeschool partnership programs that allow families to participate in classes a la carte and create an educational program from a mix of providers. Numerous districts in Michigan have these programs, allowing students to access classes both inside and outside of school at no cost to them.

Innovative charter school networks, like the Epic Charter Schools in Oklahoma, are unbundling enrichment and extracurricular activities. Students who enroll in Epic’s online program have access to a $1,000 “learning fund” to use for everything from Karate lessons to art classes. The school manages the money and parents have to choose from approved vendors but have a huge amount of flexibility in how they direct those dollars.

Tutoring and remedial programs are a final academic function that could be unbundled, as achievement gaps between students have been stubborn for many decades and some districts may be misusing funding provided for these services. If schools cannot use remedial funding well, perhaps parents can find a better way.

These are just a few examples of entrepreneurial educators looking at ways to diversify the offerings available to students. There are many others.

This series will consider five areas that states should allow to be unbundled from the public education system:

• Teacher Professional Development and Classroom Supplies

• Tutoring and Remedial Services

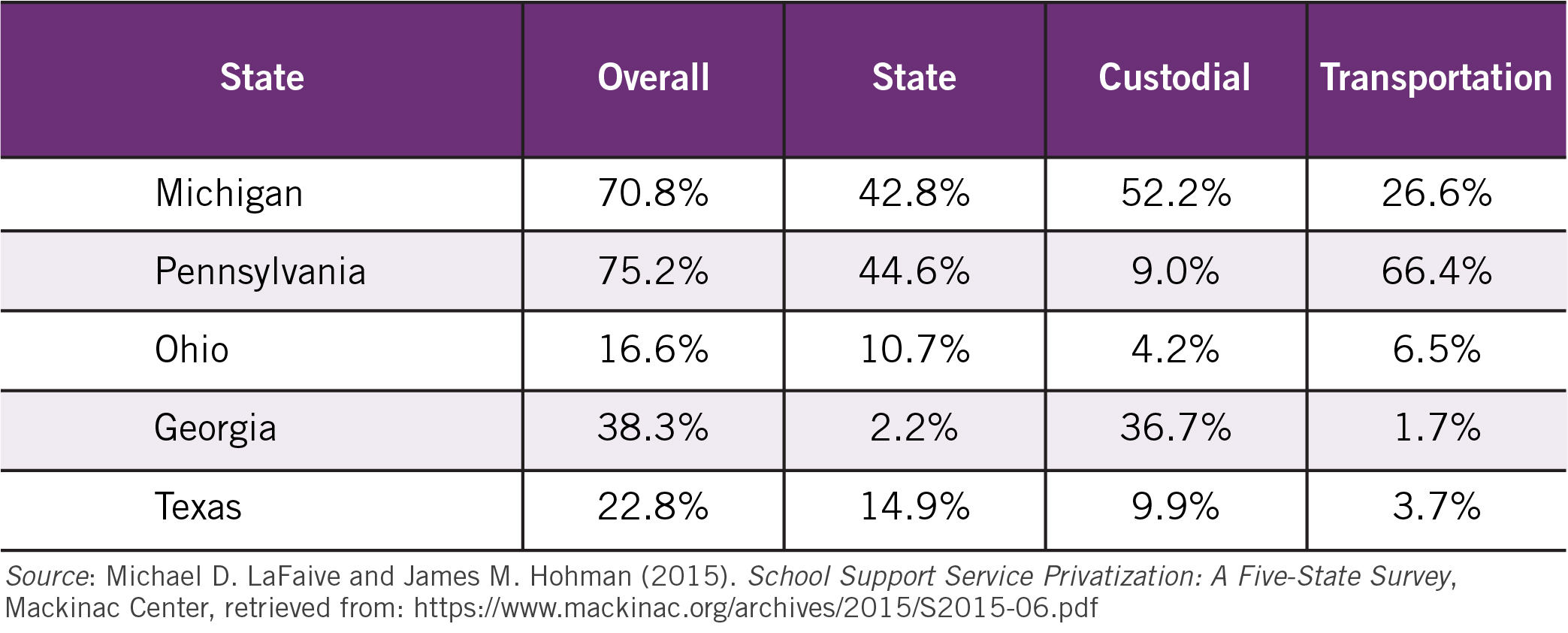

A common criticism is that this kind of unbundling will invite avaricious for-profit providers to enter the schoolhouse. Well, if that is your fear, you’re a bit late. Here is a look at the breakdown of school districts that already outsource school services to private providers.

Percent of school districts that outsource school support services to private vendors for food, custodial and transportation services

Disasters strike schools. Whether it is hurricanes, tornadoes, nasty strains of flu, student suicides, or a host of other traumatic events, schools have to be able to cope with unexpected shocks. One way to do that is to decentralize and unbundle to spread decision making across numerous actors. This prevents one decision or decisionmaker from affecting every student in a state or district. This will also serve to create a vibrant marketplace of educational providers, striving to offer better products at lower costs in each of these five areas. Everyone wins.

Read more from The Unbundling Series:

How K–12 Education Could Do Transportation Differently

Three Ways Public Schools Can Rethink Food Services

A New Way to Approach Teacher Professional Development and Classroom Supplies

Rethinking How We Deliver Remedial Services to Students Who Need Them

Three Policies That Would Improve Schools’ Core Education Services