Unbundling: Three Ways Public Schools Can Rethink Food Services

School districts spend about $24 billion on food services each year. According to the USDA, approximately 29.8 million students receive school lunch every day through the National School Lunch Program. That’s about 60 percent of public K-12 students in the country.

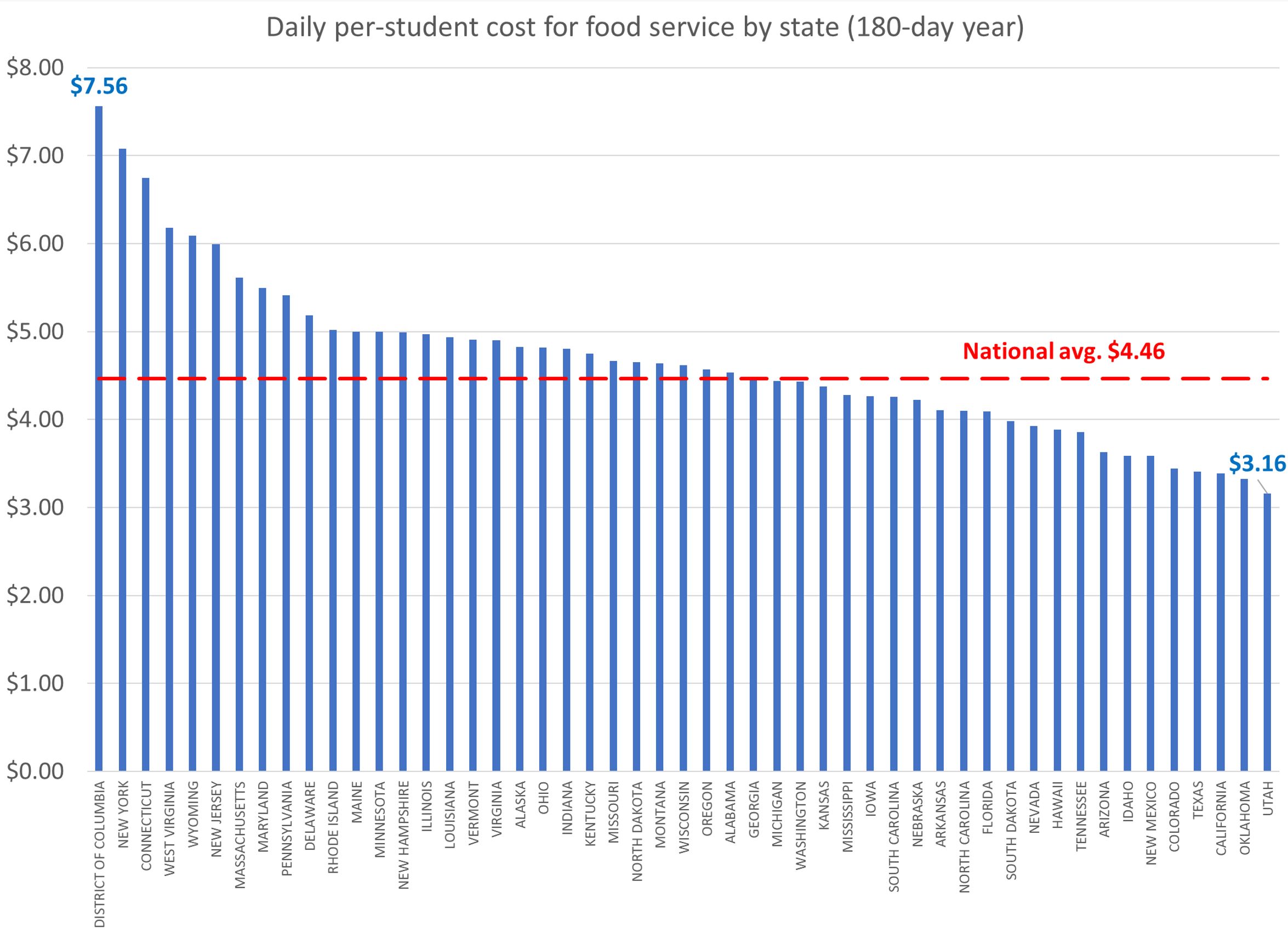

Nationwide, the cost of providing food services on a per-pupil basis, after adjusting for inflation, rose from $890 to $1,097 between 1998 and 2017, an increase of 23 percent. Put another way, the public school system spends about $4.50 on average each day to feed each student (based on a 180-day school year). These costs vary across states and will also vary within states across school districts.

Six states plus the District of Columbia spend more than $1,000 per student on food service. That’s more than $5 per student each day, respectively. As with transportation costs, D.C. spends the most in the nation on food service, more than $1,350 per student. At the other end of the distribution, Colorado, Nevada, and Utah spend around $600 per student on food service, or around $3 per day.

What do students get for this money? Opinions differ.

As mentioned in the introductory post to this series, low-quality food is a consistent complaint of students, parents, teachers. When kids don’t like food, they don’t eat it. When they don’t eat it, it gets wasted.

In 2014, the Government Accountability Office released a report on the National School Lunch Program. It is instructive. Starting in 1994, school lunches have had to be consistent with federal dietary guidelines for Americans. In 2010, congress passed The Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act which changed requirements around the portion size, caloric content, and nutritional makeup of school lunches. According to that law, school lunches must:

• Include fat-free or low-fat milk

• Limit amounts of meat and grains

• Include whole grain-rich foods

• Include both fruit and vegetable choices (although students can decline them)

• Require students to take at least a half of a cup of fruits or vegetables

The law also set maximum calorie levels for lunches, banned trans fats, and created targets to reduce sodium.

Kids hated it.

In the wake of these changes, the GAO documented a substantial drop in the number of students who paid for federal lunches. According to survey work “state and local officials reported that the decreases were influenced by changes made to comply with the new lunch content and nutrition standards.” Some school districts started dropping out of the program altogether as the losses they absorbed from students wasting food overwhelmed the subsidy the government sent.

The Trump administration rolled back many of the regulations that had been promulgated to comply with the law in early 2020, but it remains to be seen what that will do to improve the quality of school lunches.

So what can be done to help schools and school districts “unbundle” food services?

• The Federal Government needs to rethink its regulation of school lunches. Yes, it is important that students have healthy lunches, but transitioning children to a healthier diet is a society-wide endeavor. If schools are the only institution trying to get kids to eat their broccoli, they are not going to be able to get it done. The federal government needs to be realistic about the types of things it can get children to do and not do and give as much flexibility to local schools and districts to craft menus that are best for their children.

• Schools and Districts can take a hard look at their participation in the federal school lunch program. Several school districts across the country have chosen to opt out of the federal school lunch program because the waste that comes from the meals that are required costs more than schools and districts just providing lunches themselves. Schools and districts should take a hard look at their finances and ask if they could do it better, with higher-quality food and less waste, if they go it on their own.

• Schools and districts can partner with local restaurants and non-profits to provide better meals for students. Especially in the time of the coronavirus, there is excess capacity in restaurants and catering businesses that could be used to help prepare school lunches. Perhaps a school could work with a restaurant or catering business that has seen its demand drop because of the coronavirus to cater school lunches for a day or two a week. Similarly, networks of restaurants that already collaborate on a variety of charitable endeavors could launch an initiative to get chefs and restaurateurs to work with schools on better school meals.

There are all sorts of fun and innovative things schools and districts could do to rethink their food services. Schools could have kids learn how to buy produce and create their own meals. They could create culinary arts programs that make the school’s lunches. Schools could have culinary students work in local restaurants in exchange for those restaurants designing and even delivering school lunches. The possibilities are definitely out there.

To get there, we need to improve the regulatory landscape and change the mindset of educational administrators.

Read more from The Unbundling Series:

Five Services Public Education Should Do Differently

How K–12 Education Could Do Transportation Differently

A New Way to Approach Teacher Professional Development and Classroom Supplies

Rethinking How We Deliver Remedial Services to Students Who Need Them

Three Policies That Would Improve Schools’ Core Education Services