America’s Public Worker Pension Crisis Hits Primetime

Pensions hit primetime. PBS recently aired an episode of Frontline that reported on public employee pensions in Kentucky. This is an issue that affects so many Americans, not only the workers who benefit from pensions, but also taxpayers that pay to help fund them. It’s also an issue that for most is probably as exciting and simple to understand as filling out one’s tax returns.

Nonetheless, an important issue and crisis that contributed to the bankruptcy of some municipal governments—including Detroit, Michigan; Stockton, California; Jefferson County, Alabama and Central Falls, Rhode Island. And it’s an issue that’s coming home to roost in some states like Kentucky.

Why should Americans care about this issue in the first place?

Well, this is about peoples’ livelihoods. Public school teachers and other public workers all over the country have entered into contracts based on a promise that they would receive a pension they can count on in their retired lives.

For these plans to work, they must be sufficiently pre-funded. Actuaries estimate the costs of benefits to be collected in the future, and workers and employers (funded by taxpayer money) make contributions to the plan. Herein lies one of the main problems facing many states.

By their own measures, all public employee pension plans in the U.S. reported $1.38 trillion in unfunded liabilities in FY 2015. This means plans have $1.38 trillion less on hand than they owe for benefits that have been accrued. Future taxpayers will have to pay this bill.

Some pension funds are severely underfunded, such as Kentucky, Illinois, California, Connecticut and New Jersey. For example:

- The Teachers’ Retirement System of the State of Kentucky (KRS) has about 56 cents on hand to pay every dollar it owes for pension benefits. That’s $14.3 billion in unfunded liabilities, or nearly $21,000 for each K–12 public school student in the state. (Keep in mind that this debt is for pensions only and does not include retiree health benefits—Kentucky’s medical insurance plan for teachers is funded at 27 percent).

- Illinois’s teachers’ plan, which excludes teachers in Chicago Public Schools, has just 40 cents on hand for every dollar it owes ($73.4 billion in unfunded liabilities). Again, this does not include retiree health benefits.

On the other hand, some plans, like in Wisconsin’s and South Dakota’s, are fully funded by their measures.

While not all plans face funding deficits as large as some of the states mentioned, they still face financial risk. And it is on this point that Frontline missed an opportunity to educate its viewers about a key point on this issue. After the show was over, I walked away feeling it was more misleading than educational.

The program devoted a significant part of the program discussing investors’ fees. Many viewers were likely led to believe that Wall Street is the main culprit, when in reality, it has absolutely nothing to do with the cause of the funding issues.

The funding issues materialized, and when the system’s fiscal health started to deteriorate rapidly, Kentucky Retirement Systems Board members chose to look outside for a solution. In short, they thought that they could invest their way out of mounting pension debt.

This is like someone who starts buying lottery tickets after racking up huge credit card debt. Not a good strategy to dig yourself out of a hole.

So how is it possible for pension funds like Kentucky’s to rack up such enormous pension debt?

Part of the problem in Kentucky was that politicians in the past chose to short-fund pensions. They did not make the entire actuarially required contributions. But that cannot completely explain why debt is so high. Based on data from the Center for Retirement Research, some states like Alabama, Arizona and Georgia were fully funded in 2001 and have been making full payments every year since. Today, however, these states’ public pension plans carry significant pension debt nonetheless, despite making all actuarially required contributions.

It boils down to the assumed discount rate. This is the rate of return on the fund’s investments that plans count on hitting. This assumption is a key ingredient that actuaries use to estimate the cost of the plan. If they guess right, then “dollars in” equal “dollars out.” If they guess high, then the fund generates a surplus. Miss by guessing too low, then the fund generates a deficit. Imagine making purchases with a credit card without ever seeing a price or invoice and paying several years, sometimes decades, later.

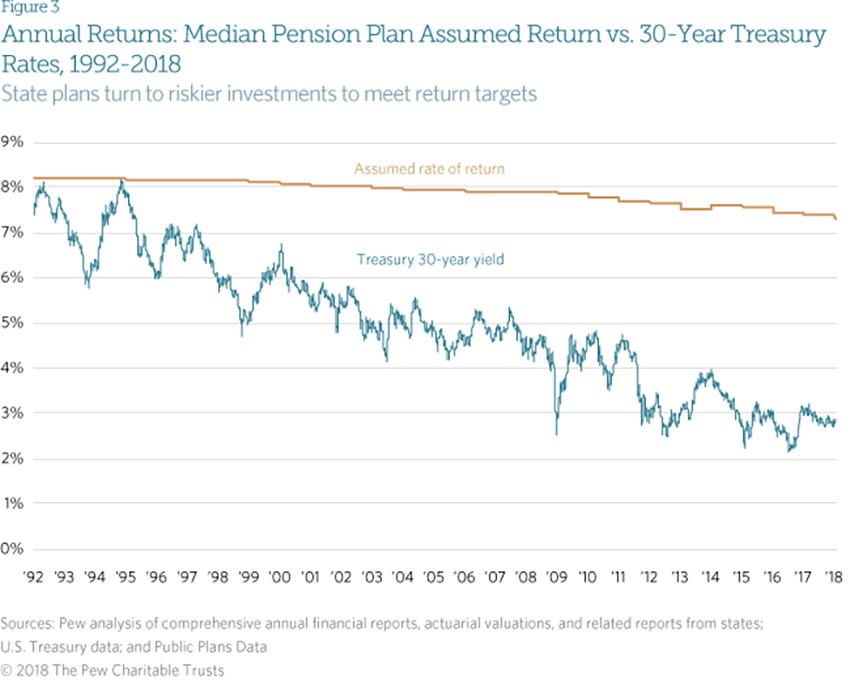

States’ pension plans typically assume that investments will generate between 7 percent and 8 percent returns on investments. In the 1980s and early 1990s, an 8 percent rate of return made sense because plans could invest in low-risk bonds, such as a 30-year Treasury bond, and reliably hit this benchmark. Public pension plans by the late 1980s were mostly well funded; the funded ratio of the median plan totaled 90 percent.

But starting in the early 1990s, yields from these low-risk bonds started declining. At the same time, pension funds continued assuming that their investments would keep earning 7 or 8 percent. Some funds lowered their assumptions about the discount rates, but not by much (certainly not enough).

In the chart below from the Pew Charitable Trusts, the assumed rate of return in the median pension plan remained above 7 percent while the yield on a low-risk bond declined to about 3 percent. The gap between the two lines represents the risk that funds must take on in order to even have a chance at hitting their marks. And taking on increased financial risk means that pension systems will face an increased chance at not meeting their targets.

Comparatively, public pension plans in other countries like the Netherlands, Canada, and the United Kingdom generally use lower discount rates to figure out required contributions. Public pension plans in the Netherlands, which assume a discount rate of just 3.5 percent, are among the best-funded plans in the world.

This arrangement of assuming a discount rate that does not accurately reflect the risk of the plan hides the true costs of pension plans from the public, where many plans for years now have been funded significantly below the actual costs.

A 5 percentage-point gap sounds small, but in the world of finance, that’s a huge gap that can generate enormous deficits.

Joshua Rauh, a financial economist at Stanford University, estimated the unfunded liabilities for all public pension plans in the U.S. based on Treasury yields. According to his analysis, pension debt for the 649 state and local pension plans in the U.S. is $3.8 trillion instead of $1.38 trillion. That’s almost 3 times greater than what state and local governments report for their public employee pension plans.

These are critical points to understanding why pensions are a problem worthy of more people’s attention.

Frontline could have interviewed a pension expert like Rauh about funding issues. Instead, Frontline devoted a significant part of the episode to blaming Wall Street for charging exorbitant fees. Regardless of who was right or wrong when it came to agency fees, Frontline should have been clear that Wall Street fund managers weren’t the cause of Kentucky’s pension woes. A more conducive approach to solving the pension problem is to properly educate people about pensions, not create scapegoats, and Frontline missed this mark.

So what can states like Kentucky do to solve their problems?

As I wrote before, systemic change is a must.

Some Kentucky legislators did try to pass a pension reform bill which would have created a sensible plan for new workers only. The intention and bill was right. Unfortunately, their approach created a problem. (It turned out that slipping a pension reform bill into a sewage bill during a committee hearing and without public comment wasn’t a good strategy.)

Reform is needed.

The longer some states delay, the tougher their decisions and the more people–current and future taxpayers and public employees— that will be put at risk. But even if states manage to pass pension reform, they still will have to somehow manage massive pension debt. And a nontrivial number of states face some very deep holes. Unfortunately, none of the options on the table are desirable. States will have to make tough decisions.

There is at least one policy that can help, though, and that is private school choice.

These programs have generated significant taxpayer savings over the last couple decades. Cumulatively, voucher and tax-credit scholarship programs have generated up to $6.6 billion cumulatively in taxpayer savings, or more than $3,000 for each voucher and scholarship provided for students. And given that programs are available only for disadvantaged students, expansion of these programs, plus introduction of new programs, can generate even greater savings.

This means that private school choice programs can act like a release valve for states that are facing severe pension pressures. And they could have this fiscal benefit along with the benefits to families that come along with introducing and expanding educational choice.

More Americans should be paying attention to pensions. And policymakers can do well by thinking about policies like educational choice as complements to pension reform.