New report shows K-12 staffing priority crowds out state and local government services

On capitol hills and in news outlets across the country, a frequent sentiment echos: “K-12 staffing is not a budgetary priority.” In fact, the opposite is true.

All fifty states and the District of Columbia have seen a positive public school staffing surge between 1994 and 2022, according to a new report by EdChoice Friedman Fellow Ben Scafidi. Scafidi found that K-12 staffing increased at higher rates than state and local government staffing, crowding out similar investments in state and local government employment.

Staffing surges, like the ones observed in K-12 education, occur when staffing increases beyond what is needed to accommodate the population served. In previous work, while overall K-12 staffing has surged to new heights, teacher salaries, when adjusted for inflation, have been relatively flat in recent decades. Meanwhile, there have been large increases in per pupil spending.

This new report shows that there has been another significant opportunity cost from the public school staffing surge—employment growth in state and local government employment (outside of K-12 and higher education) has been far less than the growth in the state populations they serve.

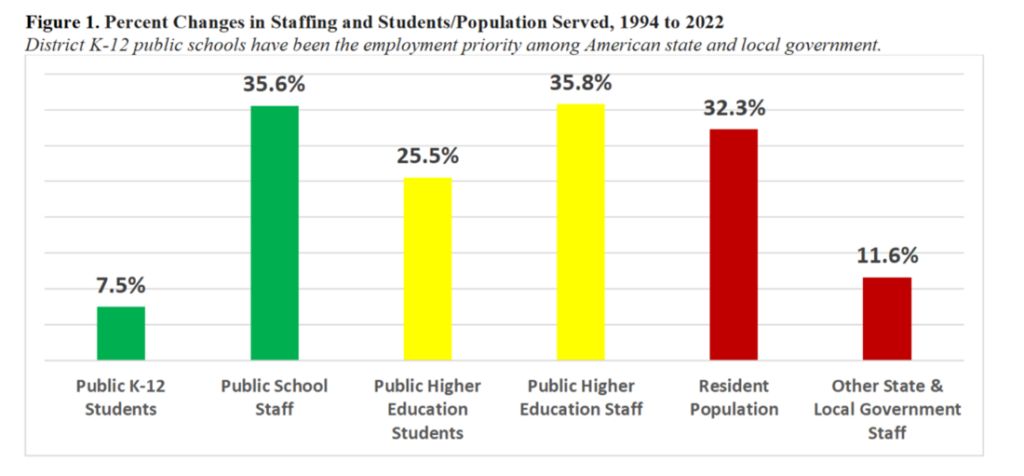

Nationally, as the U.S. population increased by 32.3 percent between 1994 and 2022, the increase in all other state and local government staff increased by only 11.6 percent. All other state and local government employment includes all functions except K-12 public schools and public higher education.

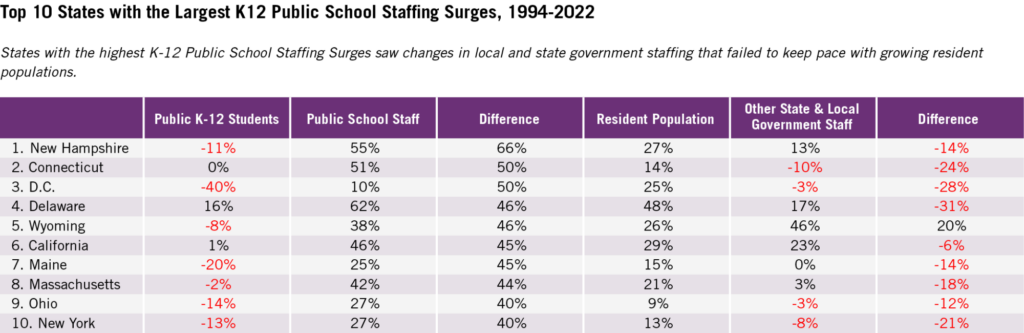

New Hampshire has seen the largest public school staffing surge. While their K-12 student population declined 11% from 1994-2022, their public school staff increased 55%. In other words, for every one percent decrease in students, roughly 5.5 percent more people were hired within the Granite State’s K-12 public school system. Over the same period, their state population grew 27%, but their state and local government staffing only grew 13%, less than half the rate that was needed to serve the increase in residents.

The top nine other states that experienced the largest public school staffing surges include Connecticut (50%), the District of Columbia (50%), Delaware (46%), Wyoming (46%), California (45%), Maine (45%), Massachusetts (44%), Ohio (40%), and New York (40%), where these percentages in parentheses represent the difference between the change in total public school staff and the change in students served.

Many of these states such as the District of Columbia lost students (-40%) but continued to hire and increase their K-12 staff. Meanwhile, investments in state and local government fell. In the case of DC, government employment (outside of education) fell 3% but the resident population increased 25%, indicating a K-12 staffing priority.

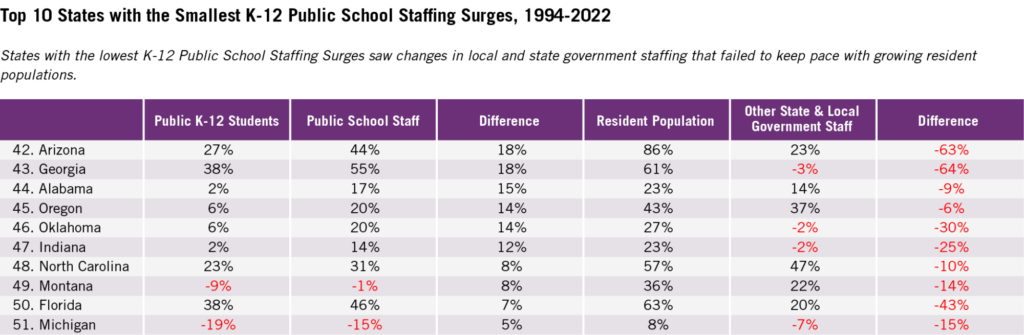

The state with the lowest staffing surge was Michigan. The state’s K-12 student population and K-12 public school staffing both declined 19% and 15% respectively, while the state population grew 8% and state and local government employment continued to decline. In this case, although K-12 staffing followed a similar trend to the K-12 student population, it did not fall as much as needed and similar investments were not made in the public sector to accommodate population growth.

The state with the second lowest surge, Florida, grew K-12 staffing 7% more than what was necessary to accommodate student growth. However, local and state government employment grew by 20% compared to population growth of 63% indicating that even states with the smallest and moderate K-12 staffing surges still maintained K-12 staffing as a priority over state and local employment.

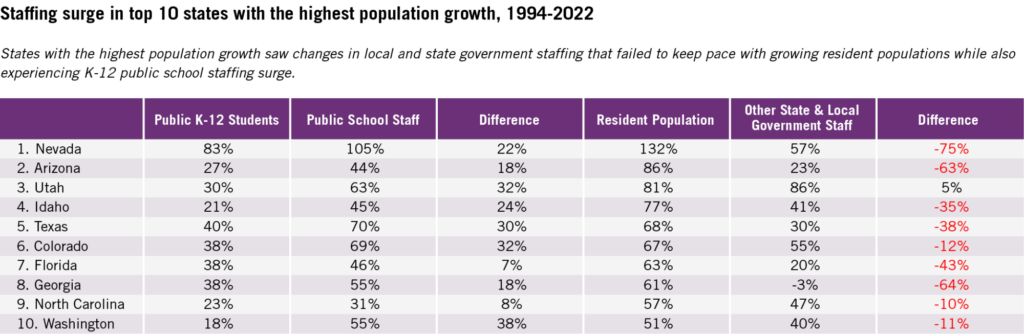

In other states, where resident populations exploded such as Nevada, Arizona, Utah, Idaho and Texas, public school staffing surges increased moderately, while hiring in the government sector cratered.

Nevada saw a 132% increase in the resident population, but state and local government hiring only grew 57%. This was 75% slower than what was needed to keep up with their growing state. Meanwhile, K-12 public school staffing saw a surge of 22% greater than what was needed to accommodate students, indicating that K-12 public schools have indeed been a priority.

Further research is needed to understand whether the slowdown in other local and state government employment was warranted, yet one thing is clear. Contrary to popular sentiment, K-12 funding and staffing is indeed a paramount priority for governments in each and every state.

And since staffing increases have been greater than what was needed to accommodate student enrollment growth, inflation-adjusted increases in per student funding given to public schools could not be devoted to increases in teacher salaries on an inflation-adjusted basis. It also has not led to associated student learning gains despite devoting vast resources to K-12 employment.

It’s up to voters and lawmakers to decide whether the large staffing surge in American public schools at the expense of staffing other state and local government functions is worth the investment.

Click here to access the full report. We also have an interactive dashboard with state-level results, accessible here.

Ben Scafidi is a professor of economics and director of the Education Economics Center at Kennesaw State University. He is also a Friedman fellow with EdChoice and the Georgia Public Policy Foundation. His research has focused on education and urban policy.