New Study Examines What the Data Say About School Accountability Driven by Parents

As the school choice debate ramps up around the country, one of the most commonly used phrases by choice opponents, and some advocates, is that voucher schools are “unaccountable.”

This conceptualization stems from the fact that most voucher programs face different accountability regulations than traditional public schools, some of which may be less transparent. On the other hand, many supporters of private school choice make the claim that the current regulatory environment is sufficient, and moreover that we should trust parents to hold schools accountable for their performance.

Despite the intense rhetoric on both sides of this debate, the effectiveness of current regulations in culling normatively bad schools has rarely been studied. Using data on the nation’s oldest parental choice program, the Milwaukee Parental Choice Program (MPCP), we decided to change that.

We created a dataset that takes into account a number of plausible reasons that a parent might select a school.

- As a proxy for academic quality, we gathered data on school performance on statewide exams.

- As a proxy for school safety, we collected a count of the number of ‘911’ calls the school made on a yearly basis.

- We also include the affiliation of the school with the large Lutheran and Catholic school network, as well as a number of other controls, such as the extent to which the school is dependent on voucher kids to remain open.

Then we looked at which schools closed during a four-year period in a survival model.[1] Such models are designed to predict the factors that increase and decrease risk of failure, in our case represented by leaving the MPCP. We examine two types of leaving the MPCP: Being forced out by the Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction (DPI) or leaving for any reason.

Forced to Leave MPCP

Schools can be kicked out of the MPCP by DPI for a number of reasons, chiefly related to financial problems with the school. The factor far-and-away most closely related to removal by DPI was the quality of academics.

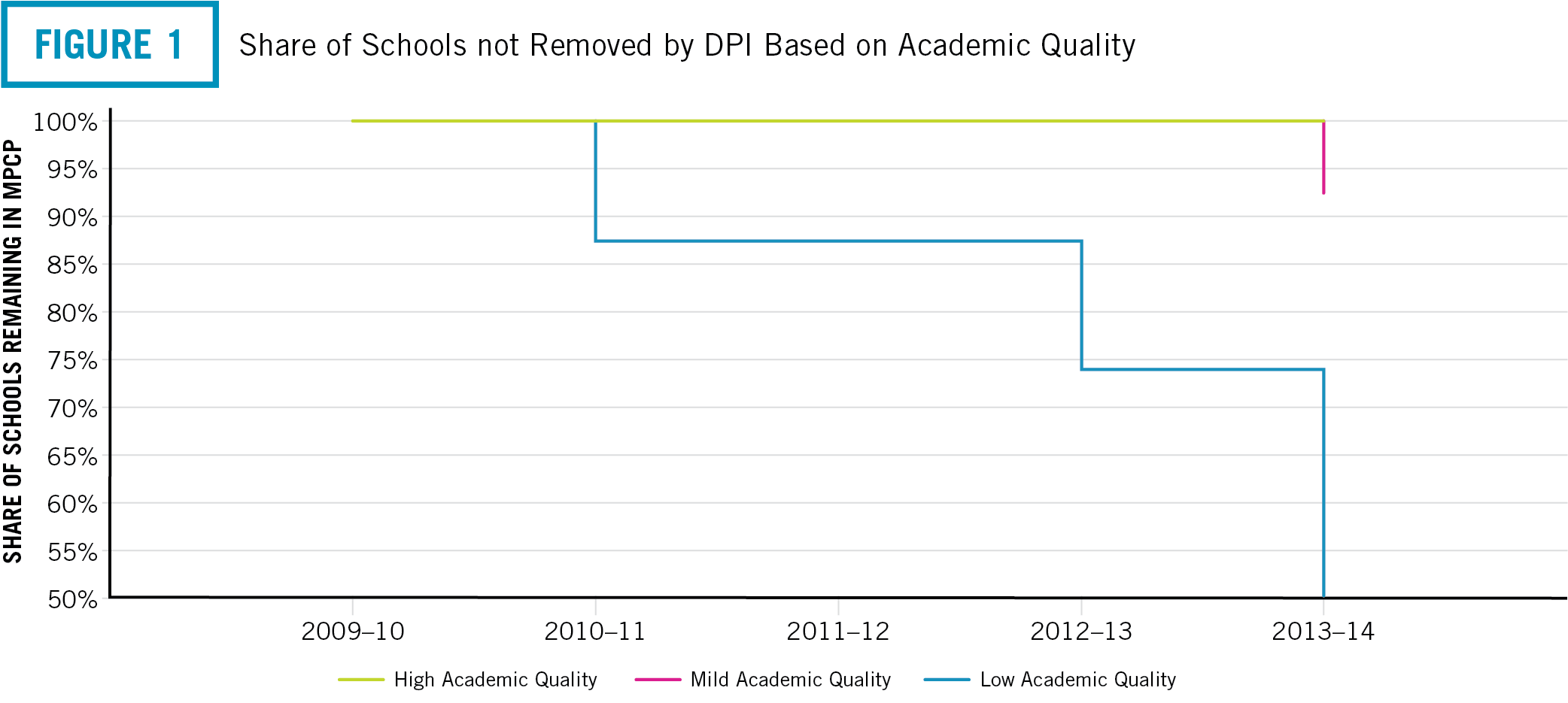

A unit shift on our eight-point scale of test scores reduces the rate of DPI removal by a staggering 98 percent. The plot below shows the share of schools remaining open in three subsets based on their academic performance. High-academic-quality schools, shown by the green line, remain open 100 percent of the time throughout the period of analysis. Low-academic-quality schools, shown by the blue line, are far less likely to remain in the program.

Figure 1. Share of Schools not Removed by DPI Based on Academic Quality

Leaving MPCP for Any Reason

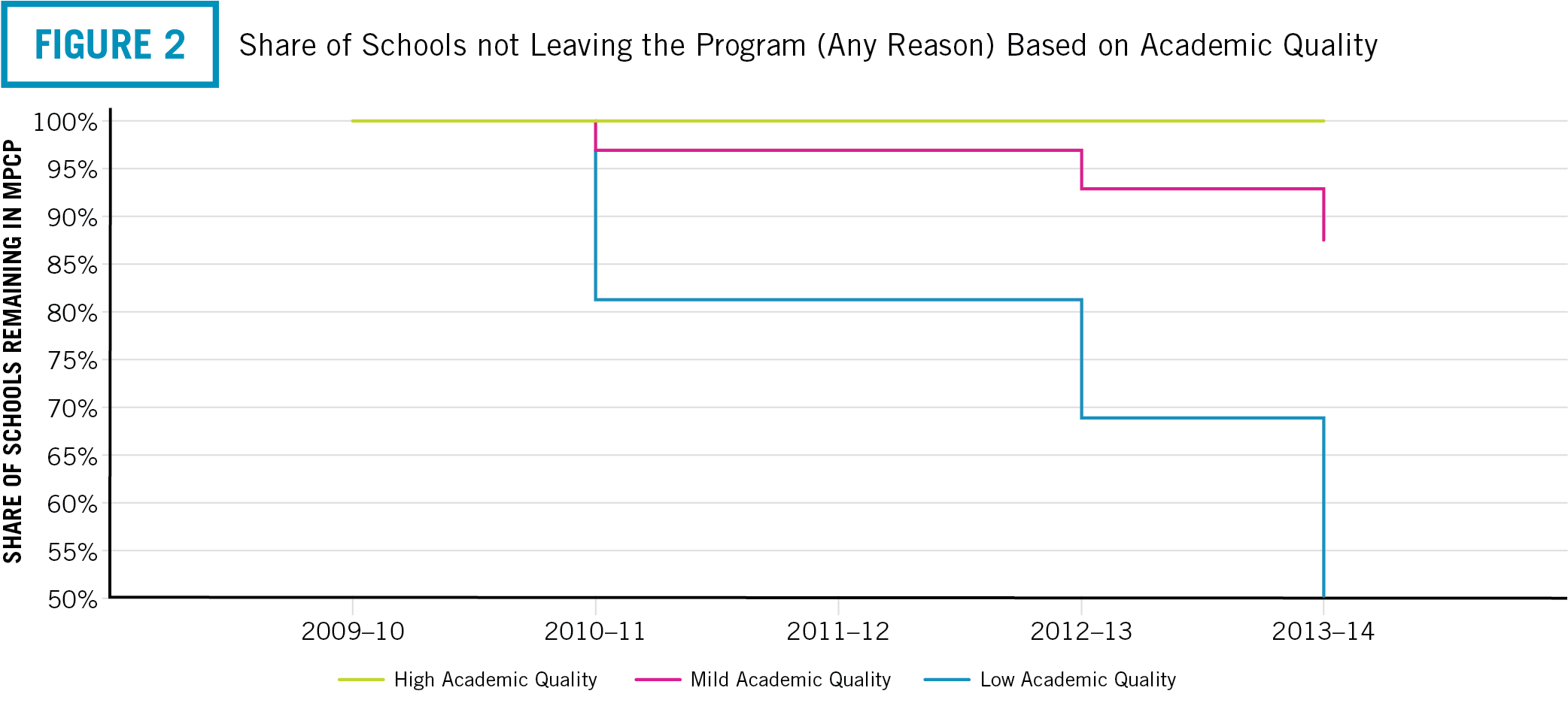

The same factors appear to be important for leaving the MPCP for any reason—either removal by DPI or a school leaving the program of their own volition. Academic quality is again the most important predictor of leaving. Here, a one-point decline in academic quality increases the rate of leaving by 85 percent—a smaller but still substantial correlation. Comparing the first graph above to this one, we see that it is the mid-academic-quality schools (red line) that were most likely to leave on their own, while the high-quality and low-quality schools largely mirror their rates from Figure 1 above.

Figure 2. Share of Schools not Leaving the Program (Any Reason) Based on Academic Quality

Parental Decision-Making

Short of school removal, it is also possible that families “vote with their feet” when it comes to their choice of schools. Do we see evidence that high-quality schools expand while lower-quality schools shrink?

To answer that question, we moved away from survival analysis to a comparison of year-on-year school growth. In this case, we find that the most important factor in school growth is school safety. A one-unit decrease in per-student 911 calls is found to increase school enrollment by 65 students.

What does not show up as a key factor in this model is academics, which is insignificantly related to school growth. While this is potentially problematic from the perspective of those that think student test scores are the only factor that should matter for accountability, we think it is due less so to the high-level of correlation between safety and academic quality.

Quite simply, schools that are doing a good job of keeping their students safe and are affiliated with the Catholic and Lutheran churches also have higher academic quality. While selecting schools on the basis of safety may be quite reasonable in a city like Milwaukee with high crime rates, the result of that selection mechanism is that kids are ending up in better academic schools.

A Clear Picture of Current Accountability Mechanism

The research here shows that low-quality academic schools are far more likely to leave the MPCP than schools of higher academic quality. Thus, the debate on accountability in school choice, at least in the context of Milwaukee, should shift from whether choice schools are accountable to whether the speed at which they are held accountable is sufficient.

Despite the patterns shown here, there are still schools that persist in the MPCP that lag in academic performance and safety. That said, policymakers should be cognizant of avoiding making the perfect the enemy of the good when evaluating alternative accountability mechanisms.

[1] Specifically, the Cox Proportional Hazard Model.