Trailblazing Educators: Celebrating The Piney Woods School’s Contribution to Black History

Editor’s Note: This is the first in a two-part series on The Piney Woods School. Read the second part here.

“It is difficult to put Piney Woods into words,” said Dr. Will Crossley, President and Alumnus of The Piney Woods School, located in Piney Woods, Mississippi. Founded over a century ago, Piney Woods School stands as a beacon of hope and opportunity, its significance intertwined with the rich tapestry of Black History and education in America.

Dr. Will Crossley, President and Alumnus of The Piney Woods School

“Piney Woods is an experience. It’s an experience from which people learn, and love, and grow. It’s more than just a school. The work of Piney Woods is about sharing with young people a different way of living, a different way of life. And so, it’s special.”

“We don’t stop at the end of algebra class. We don’t stop after the basketball game. We don’t stop even on the weekends. We’re always here, 24/7. We’re boarding our young people, so they get to learn how to learn and live simultaneously,” Crossley said.

“In my view, learning should be this ongoing thing for life for everybody. We live and we get to live that out in this special place, Piney Woods, which spans some 2,000 acres in rural Mississippi. But we didn’t start that way.”

The Humble Beginnings of a Black-Founded School in the Jim Crow South

Inspired by the high illiteracy rate of 80% in rural Rankin County, Mississippi, Dr. Laurence C. Jones, a recent graduate from the University of Iowa, embarked on a journey that would shape the course of history. In 1909, he arrived in Piney Woods with just a few clean shirts, a Bible, a couple of textbooks, his diploma, and a mere $1.65 to his name. With unwavering determination and a deep sense of purpose, he founded The Piney Woods Country Life School, driven by his faith and a vision to fulfill what he believed was God’s calling.

“Laurence Jones started this program with a single student paying with whatever they could—fruit, veggies, and nails. He was teaching kids how to read literally on fallen logs, campfire style, and [the] kids [of slaves] would come. They knew the place to come,” Dr. Crossley said. “That’s where we began, and a lot of it was about giving people a trade or a skill that they could use in life. And then we would do the “3Rs”: reading, writing, and arithmetic. It starts with an A, but back in the Old South they would drop the A and say, reading, ‘riting’ and ‘rithmetic’.” He would do those 3Rs with them so that they could create contracts and assess them fairly.”

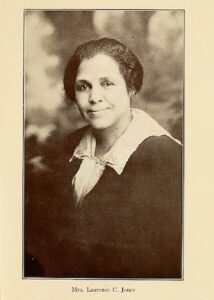

Dr. Laurence C. Jones

Several years into his work, Jones was giving a talk to a group from the community and said, ‘Education is power.’ In the context of the Jim Crow segregated south and impending World War I, Jones was accused of trying to start an uprising amongst Black people in rural Mississippi. A lynch mob formed to capture him, but Jones was living proof that good ideas can overcome hate.

“When he finished telling them his dream and his story, people started supporting it. They decided that he would contribute to the community and that he should not be killed, but he should be celebrated, and his work should be supported,” recounted Crossley.

Another important figure in The Piney Woods story was Ed Taylor. Born a slave in Mississippi, Taylor decided to go North after the Civil War and became a serial entrepreneur. He returned to his home, planted roots and left an indelible mark on Jones legacy by donating 40 acres of land, $50 cash, and a log cabin to Laurence Jones and to The Piney Woods school.

It was these types of community partnerships and support that have really allowed and protected Piney Wood’s growth for decades.

Piney Woods School students circa 1940. Courtesy of the Piney Woods School.

“What’s often not appreciated is certainly the role of Black people in how we got to where we are here at Piney Woods, but also the fact that Black folks didn’t do it alone. Laurence Jones did the work of consulting with local whites, business owners, etc. to kind of get their buy in that he was going to do this. Many whites thought he was crazy, but it was their support of the work that protected it in its earliest days because there’s stories of other whites who were intent on tearing it down,” Crossley said.

Last but not least, Dr. Crossley also credits Laurence Jones’ wife, Grace, for her contributions to Piney Woods.

“She often doesn’t get full credit because she passed away young. I think she passed in 1928, and he continued to do his work until 1970. Laurence is always recognized as the founder, but I think it’s important to recognize that they were doing this work as a family. She had also founded a school up North before she came down here, so she probably knew how to do it better than he did.”

Laurence Jones’ wife, Grace

When reflecting on Piney Woods, Dr. Crossley emphasizes the importance of community investment and collaboration in supporting historically Black Institutions.

“This is an institution that was founded by a Black man, a Black family, that was funded initially by a former slave, all for the advancement of Black children when there were no educational opportunities for Black children. So, I think that’s an important story of how we often have resources in our community that can help advance our community, and we simply need to figure out how we can collaborate to tap into those resources. This is now a 115-year-old institution, and by my measure it makes us the longest serving historically Black, boarding, preparatory program in this nation,” said Crossley.

Laurence Jones Legacy Lives on Today

In addition to its historic legacy, Piney Woods sets itself apart in its approach to cultivating its campus community and financial support for students.

Although Piney Woods is located in rural Mississippi, it welcomes students from all over the country and the world. This is accomplished through their three-pronged admissions goals to target: one third of students from Mississippi communities, one third from out of state communities, and one third from international communities.

“We have kids from Atlanta and Baltimore, Los Angeles, Detroit, kids from some rural areas throughout the South, and students from eight countries right now including Rwanda, Ethiopia, South Africa, Germany, and Brazil. So, it’s a diverse assemblage of young people that offers a learning opportunity for them as well.”

“Unlike most private boarding programs, we don’t operate on tuition but rather through a robust and dynamic donor community that ensures that Piney Woods can be made available to young people regardless of their parents’ income. No student is denied an opportunity to be a part of our program simply because their parents don’t earn enough money, and we’ve been able to maintain that now for 115 years,” Crossley said.

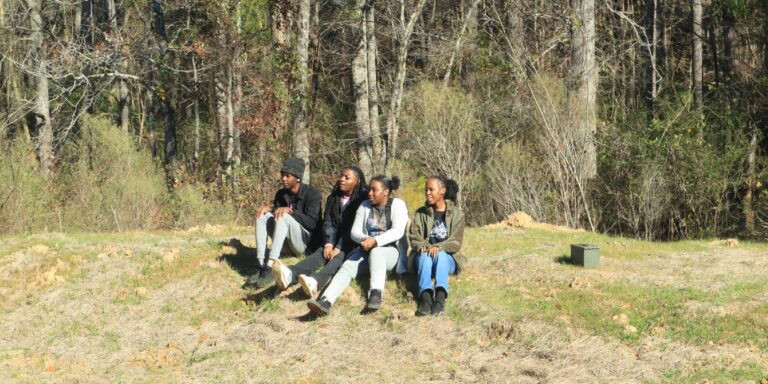

Piney Woods students enjoy nature on Piney Woods’ campus which spans nearly 2000 acres.

Students choose to apply for Piney Woods for a variety of reasons, but on a basic level, they attend because their developmental and learning needs are unmet in their current environments.

“A lot of our kids are coming because their local schools are not offering them a high quality academic or educational experience. Or they may be coming from neighborhoods where neighborhood violence makes it difficult for them to arrive safely. So, we’re often looking to invite those kids who have deep reservoirs of potential, but just aren’t in the right place to fully realize it.”

“I had a young lady referred to me by an alum. Our alum knew this student’s grades did not measure up to our guidelines but advocated for her capacity to attend Piney Woods. We discovered that her grades were poor because she was missing school. Her mom had gone legally blind and per her family’s traditions, she was the one to step in and do the duties that the mother could no longer do,” Crossley said.

“She was getting the younger kids ready for school, to school, making them breakfast, ironing their clothes, etc. So, by the time she finished all of that, she would be late to school. Then she would get in so much trouble for being late to school that she would just stop going. In her interview, I could hear the hunger in her voice to want to be in a space where she could learn and focus on herself.”

“We invited her, and she did very well in our program. We got her a full scholarship to the University of Mississippi. And the year after she graduated, her younger brother enrolled in ninth grade. He has now graduated, and he’s on a full scholarship at Berea College in Kentucky.”

Dr. Crossley, Piney Woods School president (right) poses with students.

“There is not a student here whose file I haven’t read and approved, and that takes a lot of time. But we’re blessed to be able to craft a community that is going to be the right place for the young people who we invite to be a part of it,” said Crossley.

And the hard work Piney Wood’s staff do to support their students is paying off.

“Our kids do extraordinarily well. I think this is the fifth year in a row that all of our graduates have been accepted to college. It’s a great feeling to know that you’ve made that available to all the young people you’re serving. And so, it’s a great lesson for the younger students about what the expectation is when they reach their senior year.”

From its humble beginnings over a century ago to its present-day role as a beacon of hope and opportunity, Piney Woods embodies the resilience, determination, and collaborative spirit of Black leaders in education and their supporters. As we celebrate Black History Month, we honor not only the historic contributions of Black pioneers like Laurence Jones but also the community that has come together to foster a future where every young mind is empowered to flourish and thrive.

Editor’s Note: This is the first in a two-part series on The Piney Woods School. Read the second part here.