Where the “Funding Competing Systems” Argument Falls Completely Apart

The new “gotcha” argument from school choice opponents is that school choice is inefficient. Charter schools and private schools create redundancies by duplicating the services, systems and governing structure of public schools. Some even take it a step further and argue that choice robs from traditional systems, and if it would go away, all that money would be put to better use in the one best system.

Earlier this year, the Kansas City School District published a “System Analysis” that made a version of this point. It looked at the number of administrators and spending created by having a school district and charter system of approximately equal size in the same district—and then compared it to other districts that didn’t have charter schools to show the “inefficiency” of the Kansas City model.

It’s not just Kansas City. If you follow the school choice debate on social media, you see a lot of this as well. Whether it is stretching special education dollars or burdening transportation system, the “inefficiencies” and “redundancies” of choice are frequently mentioned. So, it’s an argument worth exploring.

Let’s put the argument plainly: A school district has a superintendent, but so does a charter school network in that district. Do we really need two superintendents? Isn’t that inefficient?

To answer those questions in order: Yes. No.

To be efficient is to achieve a goal with as little cost as possible. But note the first part of that sentence, to achieve a goal. Just because something is inexpensive doesn’t mean it is efficient. It could be bad. (Case in point: cut-rate wireless providers; if your phone doesn’t connect you to the rest of the world, it’s not much more than an overpriced calculator.) Similarly, just because something is expensive doesn’t mean it is inefficient. It just might mean that whatever needs to be achieved costs a lot to do.

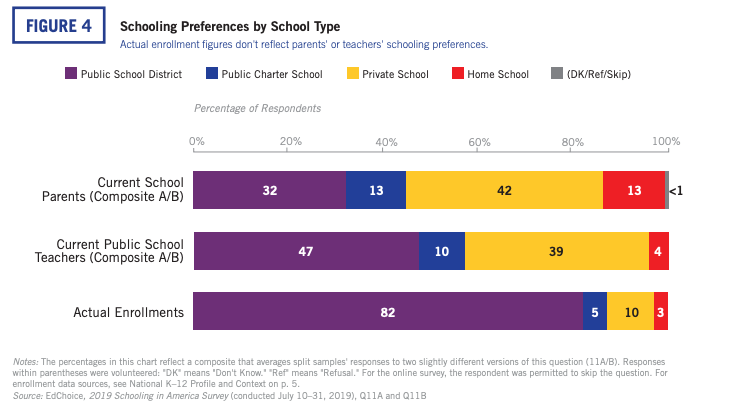

Traditional public schools, on the whole, are not meeting the goals that all families have for them—not even for the children of teachers who work there. We know this because when choice options are made available, millions of families choose to take advantage of them. If traditional public schools were the one best system, no one would want to leave.

This is why we have school choice options—what school choice opponents would call “distractions” or “redundancies.” We don’t say that airliners are inefficient for having backup electrical and hydraulic systems. Sometimes systems fail, and we need to make sure that people are protected.

If families in a district need to have a charter system and a traditional system, even with a superintendent at the helm of each, then that is what they need. Both should strive to be as efficient as possible, and needless bureaucracy, in charter or district schools, should be avoided. But some redundancies are necessary. This might just be one of them.

But what about the argument that if the school district had all of the money that would solve all of their problems. Let’s head back to Kansas City, shall we?

There was a time when there were no charter schools in Kansas City, and the school district got all of the money. Things, to put it bluntly, did not go well. The school district was overbuilt. As Joshua Dunn chronicles in Complex Justice, his great history of education in Kansas City, it was all the way back in the 1980s that a federal judge excoriated the inefficiency and waste within the Kansas City school system. Nevertheless, that judge granted more than $2 billion in new spending in the district to improve facilities, reduce class sizes, and give teachers raises. It did not fundamentally alter the poor quality of school offerings in the city. In fact, it only drove more inefficiency, waste, fraud, and abuse.

Charter schools were authorized only after this massive infusion of capital did not lead to the results that advocates promised. But at that point, this massive, overbuilt system hung like a millstone around the necks of anyone looking to try something different in the district, in either the traditional public or charter sectors. The thriving charter school sector has emerged in spite of that millstone, not because of it.

As a nation, we spend more than $12,800 per student. That’s more than the UK, Finland, Korea, Sweden, the Netherlands, France, Germany, Japan, Italy, Australia and every developed nation other than Norway. Yet for the better part of a decade, parents and teachers have been telling us their schooling preferences aren’t lining up with what the system is giving them.

There’s got to be a more efficient way to reach our goal of a well-educated public. Putting all of our money in one basket—the traditional public school system—hasn’t worked as promised.

What if instead of starting with the school system, we started with families? What if we start by asking what they need, what problems they have, and what services will improve their children’s lives. Then, we look to the community to see what resources are already out there. Where are schools in existence (public, charter or private) that are meeting these needs? Where are organizations or institutions that could start or grow schools to serve children? What places need new schools?

Rather than simply being a turf war, creating a schooling system should be about building, leveraging and uniting a community. I reject the argument that the only way to do that is to have a single set of residentially assigned public schools under the direction of an elected school board.

We need to refocus the efficiency discussion. The first question we should ask of a school or schooling system: Is it accomplishing what we want it to? Are families satisfied? Is the community (who pays for it) satisfied? Are the teachers who teach in it satisfied? If it isn’t, or they aren’t, the school system by definition cannot be efficient because it isn’t getting the job done, and we need to think about alternatives that will.