Will Hybrid Homeschooling Continue After the Pandemic Ends?

My new book, Hybrid Homeschooling: A Guide to the Future of Education, releases March 14. I wrote the vast majority of it before the pandemic, when hybrid homeschooling was confined to a small but dedicated group of educators and families in private, charter and traditional public school districts across the country.

The coronavirus completely changed the landscape. Suddenly, thousands of schools and districts adopted a hybrid learning schedule to comply with social distancing guidelines. A movement at the edges of the American education system was thrust into its center. Rather than growing slowly and organically (my pre-pandemic prediction), it exploded.

This could go one of two ways. One potential path forward sees families loving hybrid homeschooling and the pandemic marking a massive turning point in the way that families educate their children. In this story, the pandemic was the spark that lit the tinder that was dissatisfied parents considering new options, but not knowing what was out there or what was possible.

It could also go pear-shaped. Low-quality hybrid schooling hastily cobbled together by unprepared school districts could poison the well and turn parents off from this potential option. Early survey data points to this possibility. According to a national survey of parents conducted by Education Next in November and December of 2020, “The hybrid model receives the weakest endorsement. Parents of only 59% of the children experiencing hybrid instruction give a thumbs up, while parents of 69% and 66% of those in the in-person and remote modes, respectively, give a positive response.”

When we added a question to our monthly Public Opinion Tracker in January asking if parents would consider hybrid homeschooling after the pandemic ends, I expected to see very little support for the idea.

I was wrong.

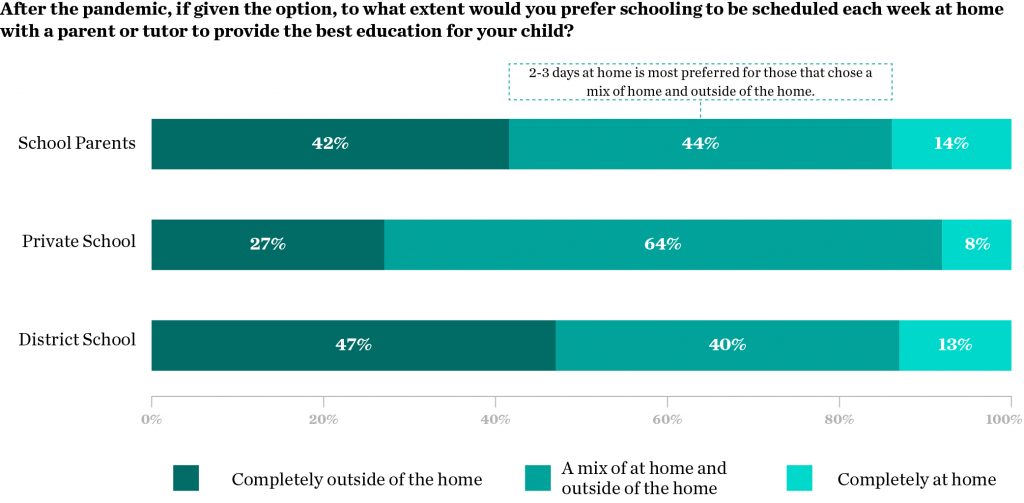

Amongst all school parents, 44 percent said that they would prefer a mix of home and school-based instruction in the future. It was the plurality choice. Amongst private school parents, almost two-thirds of respondents said that some mix of home and school would be their preference in the future. Amongst traditional public school parents, it was 40 percent.

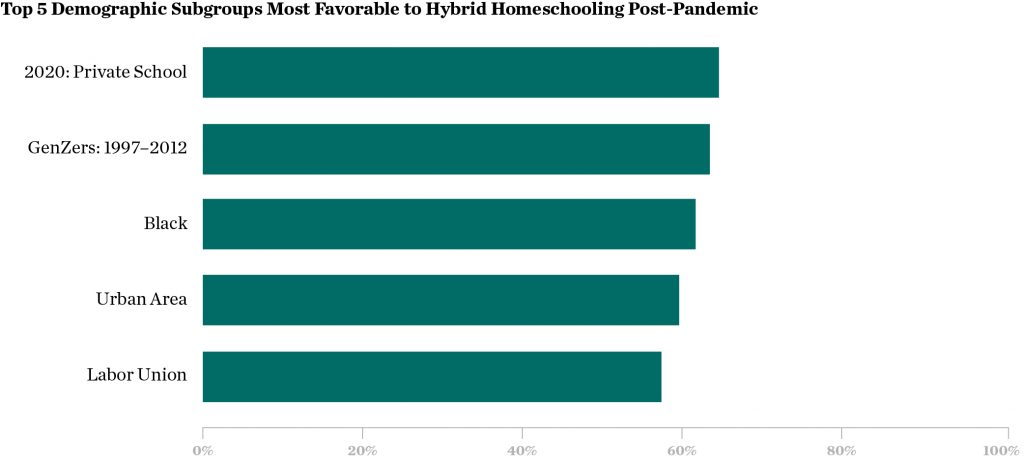

When we look under the hood at the cross tabs (the smaller demographic divisions in the sample), some even more interesting data emerge. If we look at the five subgroups most interested in hybrid homeschooling, we see private school parents, GenZers, Black families, families from urban areas and those with a household member in a labor union as the most enthusiastic about hybrid homeschooling.

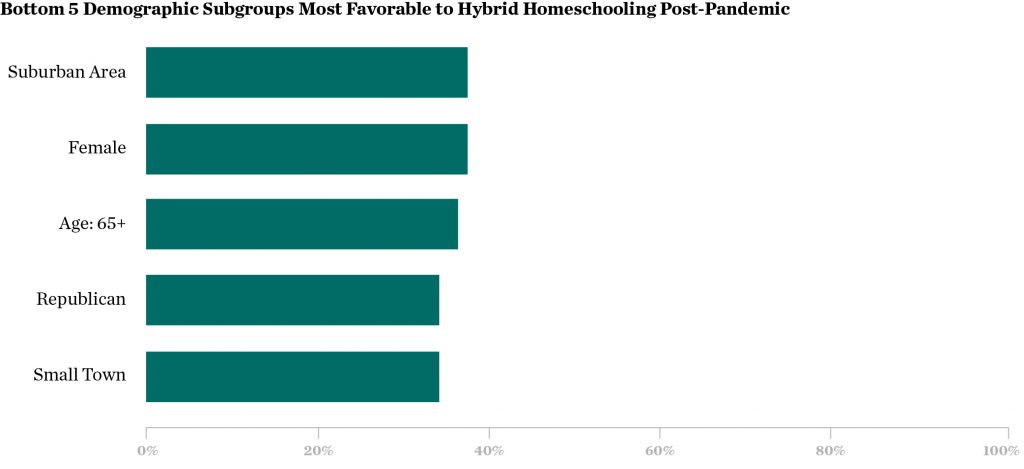

When we look at the bottom five, or the five subgroups least likely to consider hybrid homeschooling after the pandemic, we see those from a suburban area, female respondents, respondents over the age of 65, Republicans, and those in small towns. All five hovered right around one third stating that they would considering hybrid schooling after the pandemic.

These data are fresh off the computer and might change over time as the school year and pandemic roll on, but I think we can make a couple of interesting, if early, connections.

The fact that urban families and Black families were much more likely to prefer hybrid schooling while suburban and small town families were among the least likely might point to school district reactions to the pandemic as a driver of interest in hybrid homeschooling. Across the country, suburban and rural school districts were more likely to remain open for standard five-day-per-week schooling for much of the course of the pandemic. (We can debate the wisdom of that at some point in the future.) Urban districts (which have large numbers of Black students) were more likely to close to in-person instruction and remain in remote instruction for much of the following school year. The fact that the families who were most likely to attend the districts that are closed down to in-person instruction suggests they might be looking for a new option in the future.

It shouldn’t surprise us that those over 65 would be less interested, as they likely don’t have young children and if they did might be less able to provide home-based instruction than their younger and more energetic peers. Nor perhaps should it surprise us that women are less likely to be enthused about the option, as the burden of instruction might fall on them. But I was surprised to see Republicans less interested, as traditional homeschoolers tend to be more conservative than the average family. I’ll have to think about that one a bit more.

Finally, it must be noted that these are simply asking for preferences, not a commitment. I’m interested in moving to a beach somewhere and working as a bartender in a swim-up bar, but that doesn’t mean that I’m going to do it. I have considered it, though. To really get our arms around trends, we’ll have to see how real enrollment patterns change.

That said, interest is important. The past year’s experiments in hybrid schooling haven’t ruined hybrid homeschooling’s chances of growing in the future.

There are many burdens that families face when moving from interest to reality, and public policy can help ease some of them. Getting families education savings accounts, which would provide funding for them to pay for tuition at a hybrid school and to purchase the materials they need to effectively educate at home is one step. Liberalizing charter school authorizing statutes and practices to encourage more innovative school models is another. Shifting to competency-based academic standards so that traditional public schools can experiment with schedules and calendars that aren’t wedded to seat time is a third. There are others.

It will be fascinating to watch the hybrid schooling sector grow and change in the coming months and years. Parents are clearly interested. Will the supply rise to meet the demand? We’ll have to wait and see.