ESAs in Missouri: Why Things Need To Change

This is the second in a three-part series that looks at education savings accounts in Missouri and how they could empower every family and improve student outcomes.

There are roughly 916,000 students in Missouri’s public school system.

Three-quarters of the state’s schools are Title I eligible (a proxy for school-level poverty), and roughly 45 percent of students are eligible for free and reduced-price lunch. More than 13 percent of students have an Individualized Education Plan (IEP), reflecting that they have special learning needs, and nearly 3 percent of Missouri students have limited English proficiency.1

Like school systems throughout the United States, Missouri faces unique challenges and opportunities in the years ahead. At present, however, education in the state has significant room for improvement.

For example, while Missouri eighth graders outperformed the national public considerably in mathematics as recently as 2009, students across the nation have now caught up with Missouri students. Along the same lines, the percentage of Missouri eighth graders who can read proficiently has declined over the past decade.

And across the board, gaps in academic achievement and attainment (graduation rates) persist between white and minority children in Missouri, and between children from low-income Missouri families and their more affluent peers. It is clear that education in the Show Me state has much room for improvement and must change course if it is to keep pace with improvements nationally. Missouri kids deserve better.

Raw Data: Missouri Fourth and Eighth Grade Mathematics

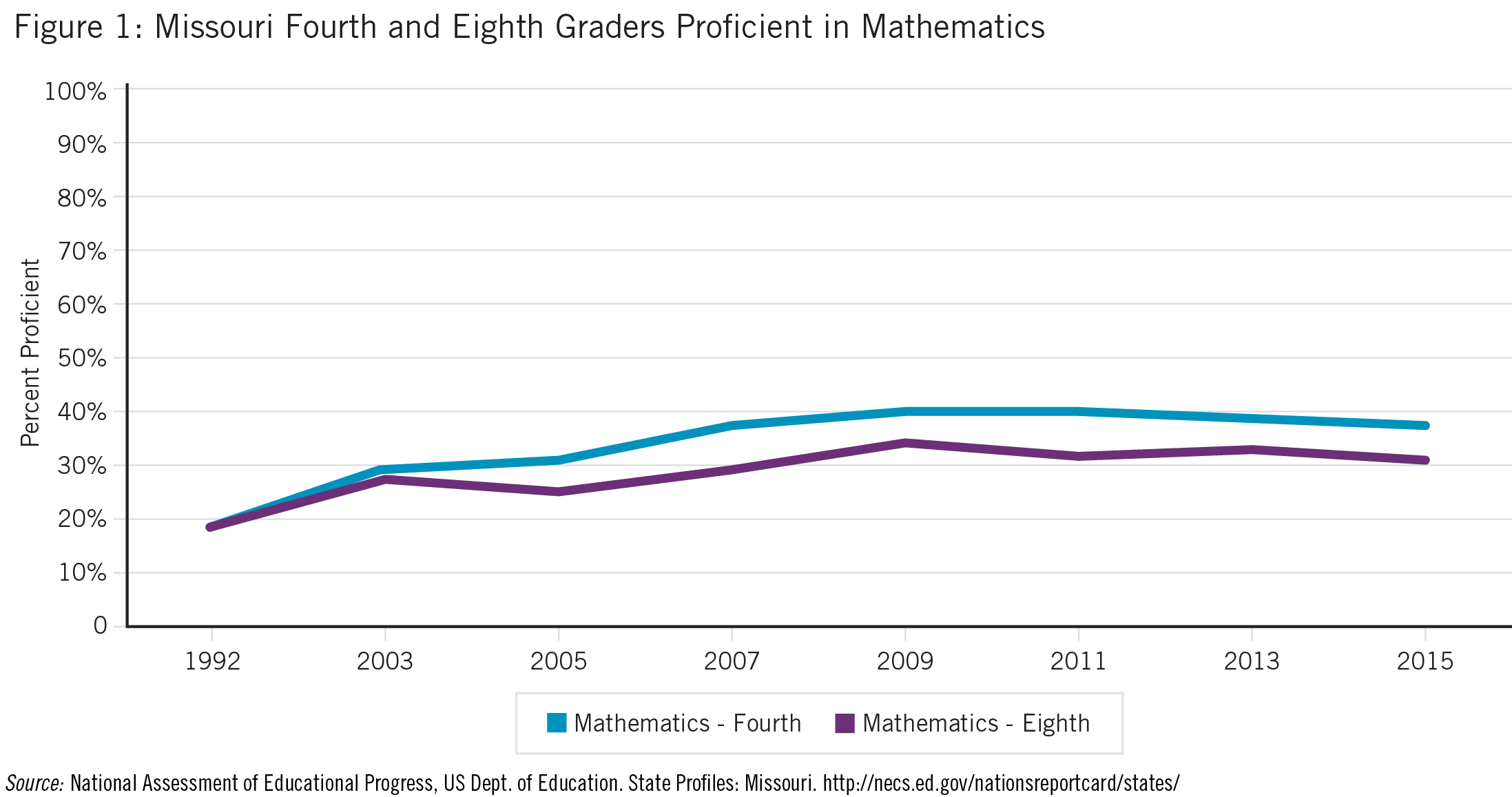

Although higher today than in 1992 (19 percent), the percentage of fourth graders who are proficient in mathematics remains low, at just 38 percent. As with fourth grade mathematics, eighth grade math proficiency remains low, with less than one third of students (31 percent) scoring proficient or better. Although that figure is considerably higher than in 1992 (20 percent), it is four percentage points lower than it was in 2009 (35 percent).2 [Figure 1]

Notably, achievement gaps between white and minority children, and between children from low-income families and their more affluent peers persist. Whereas 44 percent of white fourth graders were proficient in mathematics in 2015, just 15 percent of their black peers, and 30 percent of their Hispanic peers reached proficiency. At the same time, barely over a quarter (26 percent) of children from low-income families achieved proficiency in fourth grade math, compared to 53 percent of their peers who did not qualify for free or reduced-price lunch.3

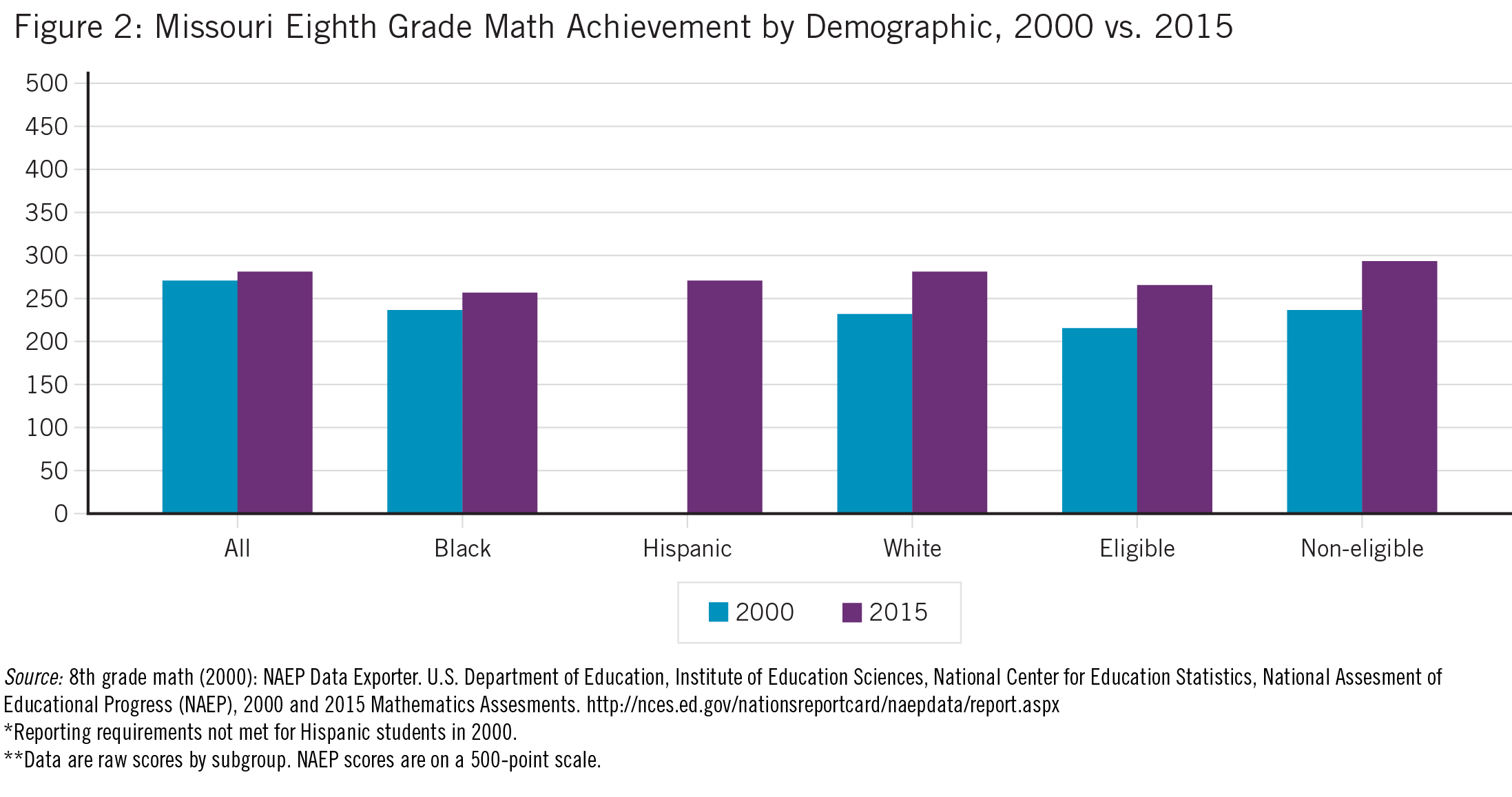

Achievement gaps also persist through eighth grade. Just 11 percent of black eighth graders were deemed proficient in mathematics in 2015, compared with 36 percent of their white peers. Twenty-two percent of Hispanic eighth graders achieved proficiency in math in 2015. For those children qualifying for free and reduced-price lunch, just 16 percent were proficient in mathematics, compared with 45 percent of children who did not qualify.4 Proficiency in mathematics achievement is also reflected in the raw score data on the NAEP, with gaps between white and minority students, and between students from low-income families and their more affluent peers becoming more pronounced between 2000 and 2015. [Figure 2]

Raw Data: Missouri Fourth and Eighth Grade Reading

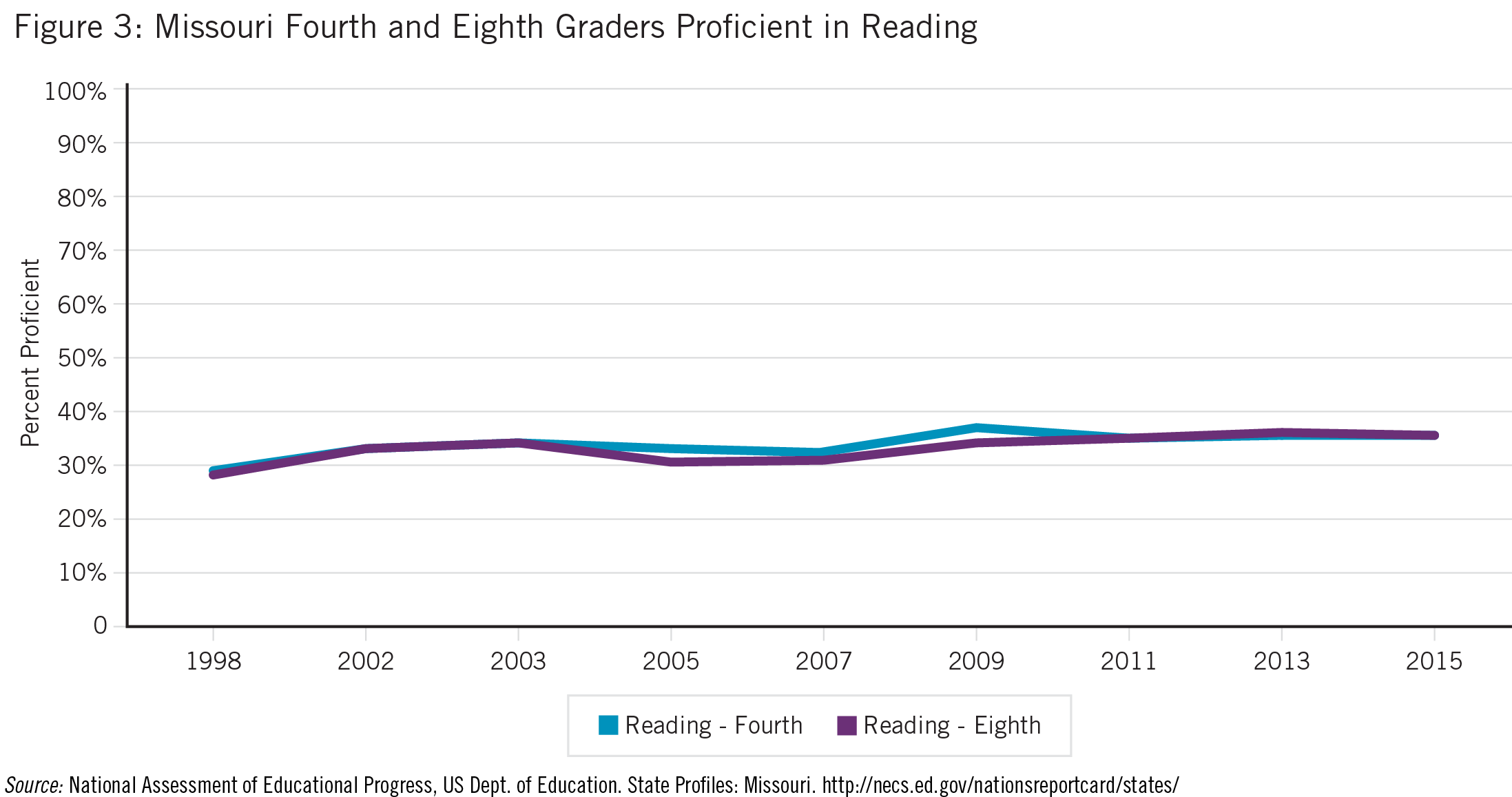

Today, just 36 percent of Missouri fourth graders can read proficiently, a proportion not markedly different than in 1992, when proficiency was at 30 percent. Fourth grade reading proficiency has been stagnant since 2009, when 36 percent of fourth graders reached the proficient level.5 As with fourth grade, just 36 percent of Missouri eighth graders are proficient in reading. Although higher than in 1991 (28 percent), reading proficiency rates have not significantly increased over the past decade.6 [Figure 3]

As with mathematics, achievement gaps are evident in the reading proficiency rates of Missouri students. In fourth grade, 42 percent of white children reached proficiency in reading in 2015, compared with 15 percent of black students and 25 percent of Hispanic students. Just 25 percent of children from low-income families could read proficiently, compared with 50 percent of their non-poor fourth grade peers.7

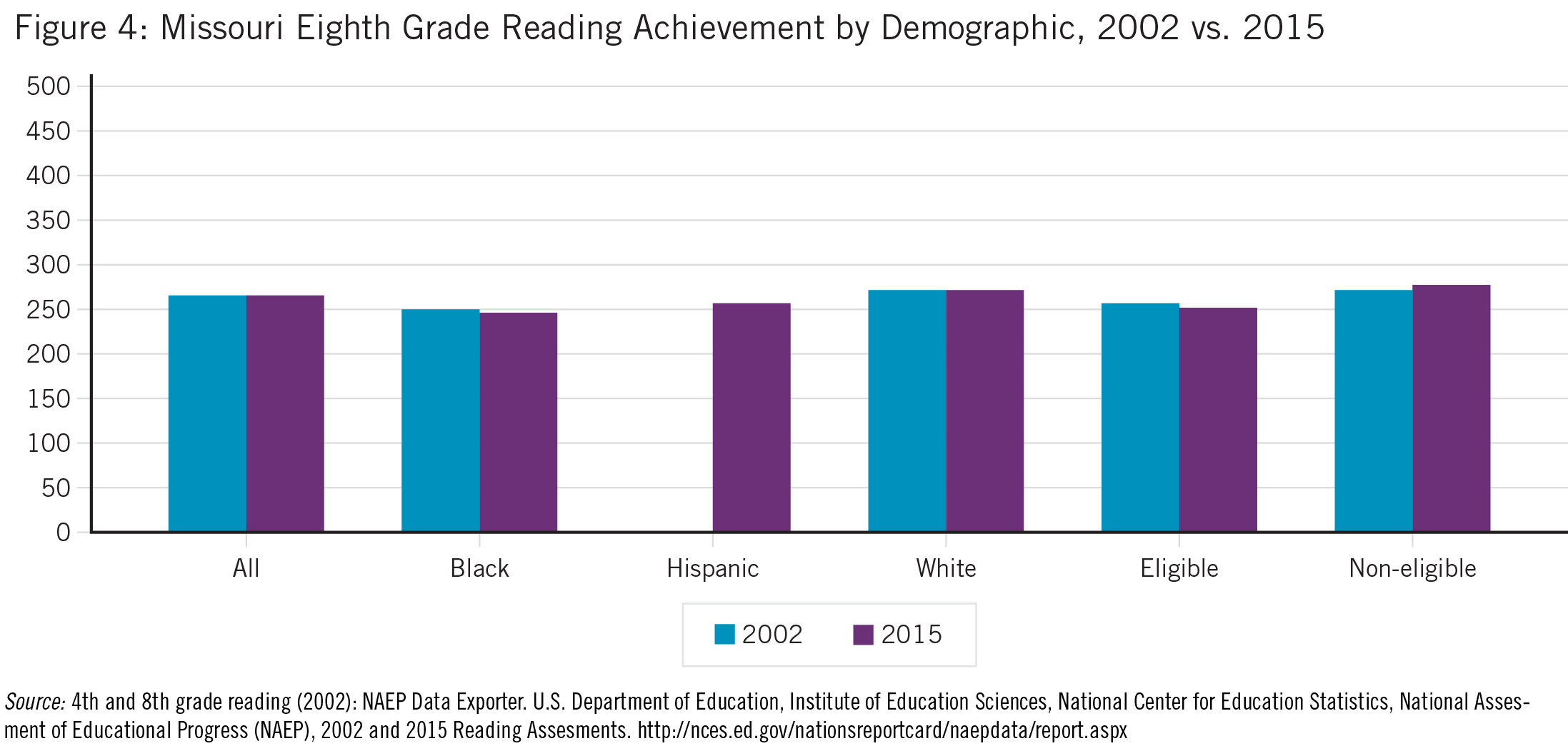

Reading achievement gaps also persist through eighth grade. Reading proficiency rates for white eighth graders stood at 41 percent in 2015, compared with 14 percent and 29 percent for black and Hispanic students, respectively. Just 22 percent of eighth graders from low-income families could read proficiently in 2015, compared to 49 percent of eighth graders who did not qualify for free and reduced-price lunch.8 Proficiency in reading achievement is also reflected in the raw score data on the NAEP. Although gaps remain between white and minority students, and between students from low-income families and their more affluent peers, they are less pronounced in reading than in math.9 [Figure 4]

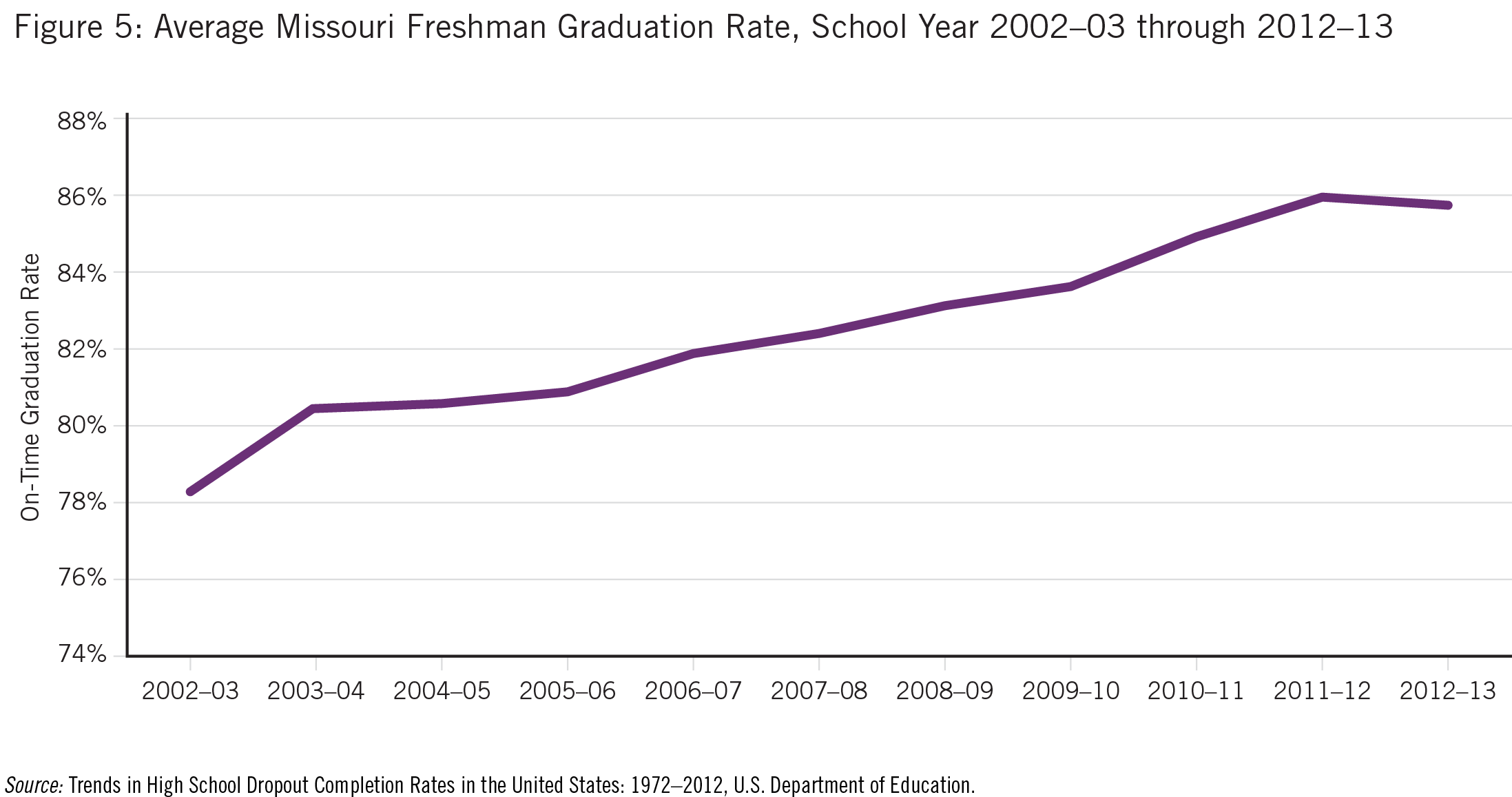

Raw Data: Missouri Graduation Rates

In the decade from 2002 to 2012, Missouri, like the nation on the whole, saw an uptick in the percentage of students graduating high school on time, as measured by the Averaged Freshman Graduation Rate (AFGR). The proportion of Missouri students who graduated on time grew from approximately 78 percent during the 2002–03 school year to nearly 86 percent during the 2012–13 school year. [Figure 5] During that year, Missouri was one of 15 states to have graduation rates above 85 percent. 10 Although that is demonstrably good news for Missouri students, a closer look at the graduation rates of subgroups of students suggests there is still significant room for improvement in the realm of educational attainment.

Source: Trends in High School Dropout and Completion Rates in the United States: 1972 – 2012, U.S. Department of Education.

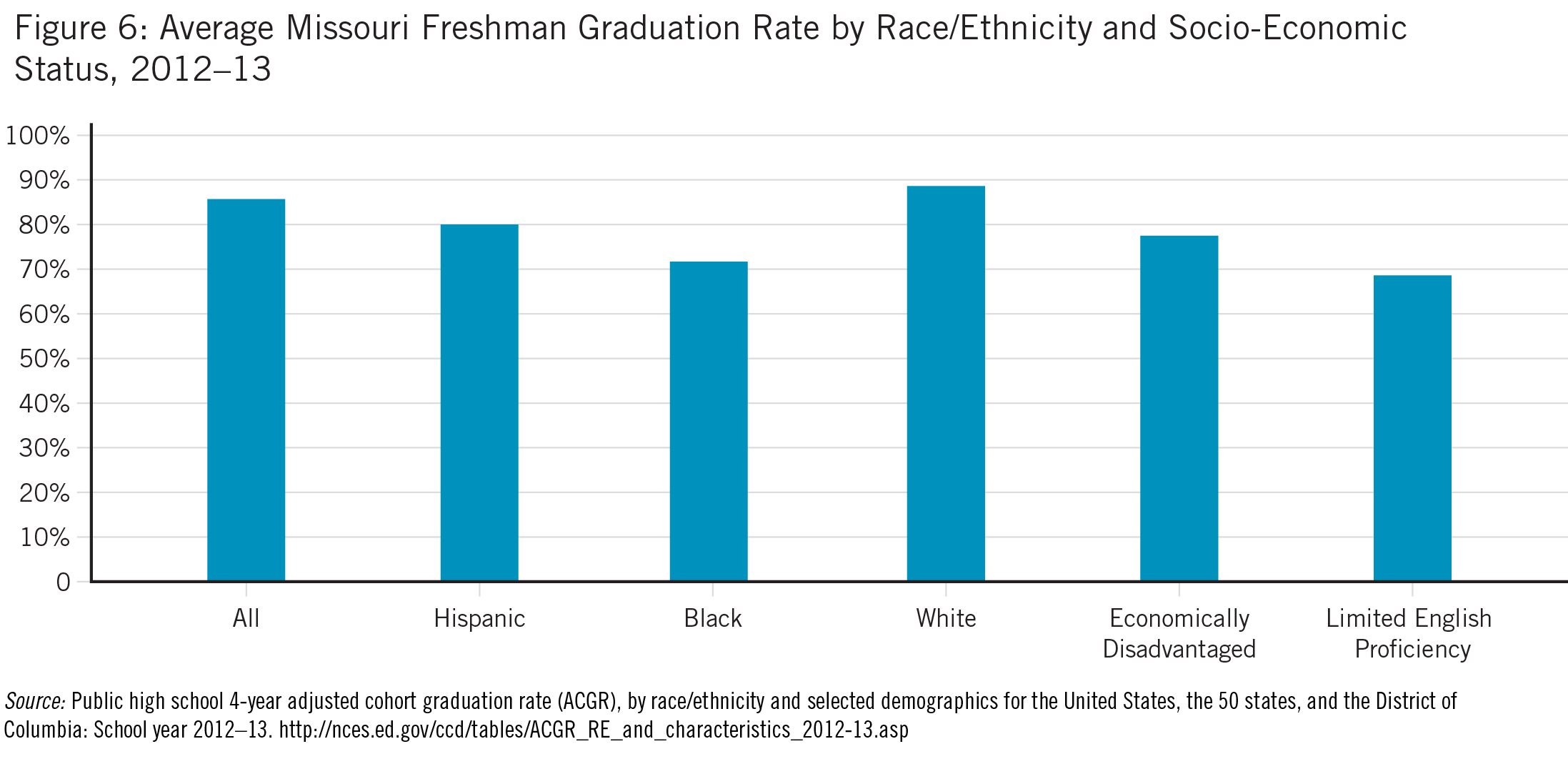

Although graduation rates for Missouri students reached approximately 86 percent during the 2012–13 school year, rates for black and Hispanic students were considerably lower, at 72 percent and 81 percent respectively. Graduation rates for students participating in the federal free and reduced-price lunch program stood at 78 percent during the 2012–13 school year.11 [Figure 6]

Demographic “Strain” in Missouri

In addition to the need for academic improvement, Missouri’s quickly changing demographic landscape creates urgency for rethinking education financing.

As an increasing number of Baby Boomers enter retirement (defined as those individuals born between 1946 and 1964), use of taxpayer-funded programs such as public pensions will grow, while their tax contributions to fund such obligations will decrease. At the same time that the proportion of individuals exiting the workforce escalates, many states will also experience a dramatic increase in the number of school-aged children. In his important and revealing report, Turn and Face the Strain: Age Demographic Change and the Near Future of American Public Education, Matthew Ladner highlights this phenomenon, which has been quantified by demographers through the use of the age dependency ratio.

The age dependency ratio is calculated by adding the total number of individuals under 18 and the total number of individuals over the age of 65 and dividing that figure by the total population aged 18 to 64 and multiplying by 100. Although the age dependence ratio is not a perfect measure of state budgetary strain, as Ladner notes, “Broadly speaking however, economists have found dependency ratios to be predictive of economic growth. When ratios are high, you have a high percentage of people out of the work force and a relatively small percentage of people trying to cover the costs of their education, retirement and health care. Under such circumstances, economic growth tends to slow.”12

By 2030, Missouri can expect a 58 percent increase in residents 65 and older (from 821,645 to 1,301,714), meaning it will have a larger elderly population than currently resides in Florida.13 At the same time, Missouri is expected to have a 6 percent increase in the population of 5 to 17-year-olds (from 1,016,516 in 2010 to 1,078,644 in 2030).14 When taken together, Missouri is facing a 25 percent increase in its combined population of individuals 18 and younger and 65 and older.15

As Ladner explains, “All 50 states will be getting older and many states will be experiencing youth population increases. The states experiencing both will have an incredibly daunting challenge to face.”16 The U.S. age dependency ratio was 59 percent in 2010, roughly estimating that for every 59 people falling within the age ranges likely not being in the workforce, 100 were in the workforce. By 2030 that figure is estimated to grow to 76 percent. In other words, by 2030, “76 people will be riding in the cart for every 100 pushing it.”17 As with the rest of the United States, Missouri will see an increase in its age dependency ratio. Missouri’s age dependency ratio stood at 61 percent in 2010, and is estimated to increase to 77 percent by 2030 – a 16 percent increase.18

The coming increase in the population of Missouri residents who are either in the K–12 system or retired, as denoted by a 16 percent increase in the state’s age dependency ratio over the next 20 years, hastens the need for policymakers to consider the future of education funding in the Show-Me State. It will become increasingly difficult to continually increase per-pupil expenditures in the public system. Not only will it become more difficult, but it is a strategy that has failed to affect meaningful gains in educational outcomes.

How Choice Can Help

We know from Greg Forster’s most recent analysis of 100 empirical school choice reports that school choice improves academic outcomes for participants and public schools.

In his Win-Win analysis, Forster found that 14 of 18 random assignment evaluations found choice participants’ proficiency scores improved as a result of using a private school voucher or scholarship. Two of those 18 studies show a no visible effect on student test scores. Also, 31 of 33 studies find the competitive effects driven by school choice programs led to improvement in public schools’ academic performance. In fact, more expansive school choice programs can be expected to lead to more positive changes for students and schools.

Furthermore, opponents often argue that choice programs are expensive and drain resources from public schools. However, Forster found that 25 of the 28 studies on the fiscal effects of school choice show such programs save taxpayers money—sometimes thousands of dollars per participating student.

Three studies show the programs examined are revenue neutral, and none find school choice programs cost taxpayers additional money. Though savings vary from program to program, the research demonstrates that educational choice has the power to save millions of dollars for taxpayers and school districts.

Not only could school choice — and specifically an ESA program — help close the gap among Missouri students and their peers both in-state and nationally, but it could also help resolve persistent financial issues plaguing so many states right now. Check out this recent post on how much Nevada’s ESA program could save that state. Those fiscal benefits and how an ESA program should be designed will be the topic of the final post in this series.

To read the first in this three-part series, visit “ESAs in Missouri: A “Barren” School Choice Landscape.”

To read the next in this series, visit “ESAs in Missouri: Designing What Works For Parents and the State Budget.”

*Opinions expressed by our guest bloggers are their own and do not necessarily reflect those of EdChoice.

—

1. State Profiles: Missouri. National Assessment of Educational Progress. (2015). http://nces.ed.gov/nationsreportcard/states/

2. State Profiles: Missouri. National Assessment of Educational Progress. U.S. Department of Education. http://nces.ed.gov/nationsreportcard/states/

3. 2015 Mathematics State Snapshot Report: Missouri. Grade 4. National Assessment of Educational Progress. U.S. Department of Education. http://nces.ed.gov/nationsreportcard/subject/publications/stt2015/pdf/2016009MO4.pdf

4. 2015 Mathematics State Snapshot Report: Missouri Grade 8. National Assessment of Educational Progress. U.S. Department of Education. http://nces.ed.gov/nationsreportcard/subject/publications/stt2015/pdf/2016009MO8.pdf

5. State Profiles: Missouri. National Assessment of Educational Progress. U.S. Department of Education. http://nces.ed.gov/nationsreportcard/states/ http://nces.ed.gov/nationsreportcard/subject/publications/stt2015/pdf/2016008MO4.pdf

6. Ibid.

7. 2015 Reading State Snapshot Report: Missouri Grade 4. National Assessment of Educational Progress. U.S. Department of Education. http://nces.ed.gov/nationsreportcard/subject/publications/stt2015/pdf/2016008MO4.pdf

8. 2015 Reading State Snapshot Report: Missouri Grade 8. National Assessment of Educational Progress. U.S. Department of Education. http://nces.ed.gov/nationsreportcard/subject/publications/stt2015/pdf/2016008MO8.pdf

9. Ibid.

10. Patrick Stark, Amber M. Noel, and Joel McFarland. Trends in High School Dropout and Completion Rates in the United States: 1972 – 2012. National Center for Education Statistics. U.S. Department of Education. NCES 2015-015. http://nces.ed.gov/pubs2015/2015015.pdf

11. Public high school 4-year adjusted cohort graduation rate (ACGR), by race/ethnicity and selected demographics for the United States, the 50 states, and the District of Columbia: School year 2012–13. http://nces.ed.gov/ccd/tables/ACGR_RE_and_characteristics_2012-13.asp

12. Matthew Ladner, Turn and Face the Strain: Age Demographic Change and the Near Future of American Public Education, (Indianapolis: Friedman Foundation for Educational Choice, 2015), p. 22, http://www.edchoice.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/Turn-and-Face-the-Strain-Age-Demographic-Change-and-the-Near-Future-of-American-Education.pdf.

13. Ibid, p. 12-15.

14. Ibid, pg. 18.

15. Ibid, pg. 41.

16. Ibid, pg. 22.

17. Ibid, pg. 24.

18. Ladner, Turn and Face the Strain.