Friday Freakout: Is Education a Consumer Good?

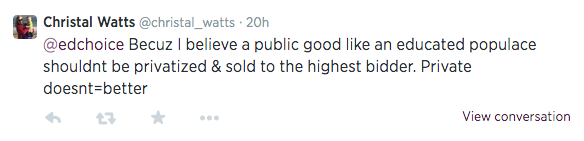

In a response to this tweet last week, the Friedman Foundation questioned what makes education a public good and examined how school choice affects it in those terms. I have a different perspective, so stick with me.

The most difficult part of this comparison isn’t between the record store and Napster. Instead, describing education as a consumer good makes people nervous.

Education is perceived as a public good and notions of consumerism, or markets, in education are controversial. However, those families who treat education as a consumer product—and who invest, buy, and sell it as such—are precisely the people getting the most out of the system. These families—savvy and often affluent—operate at an advantage to the majority of working-class and low-income families, and understanding “why” is critical to reforming “the consumption of school” and ensuring children of all stripes get an equal opportunity at a quality education.

Indeed, parents “stealing” school, which is ostensibly free, may make the strongest argument that education is, in fact, a consumer good.

First, the most successful families acknowledge they are “buying” education. This purchase is normally made through the housing market with a mortgage, but it is made nevertheless. Along with their understanding that you buy a house for access to a specific school or district, there is a companion realization that school, public or otherwise, is not free.

When school is a housing investment that includes private access—which pays dividends through the same housing market—the expectations and policing levied on the system are both higher and better than in communities where this is not understood or practiced widely. I recall a visit former New Jersey governor Jon Corzine made to Camden’s Woodrow Wilson High School during his tenure. A student there asserted to him “We don’t have a lot of stuff and equipment compared to Cherry Hill and Atlantic City. What can you do to change Wilson?”

Cherry Hill is a nearby bedroom community to Camden. What the student didn’t know is that Camden, which spends nearly $25,000 per student, and levies approximately 2 percent of its budget from local property taxes, spends far more than Cherry Hill, which raises approximately 80 percent of its budget from local property taxes and whose schools far outperform those of Camden. To wit, folks in Camden think the schools are free; folks in Cherry Hill know they aren’t.

Second, these families amplify their housing/school investment by making its benefits exclusive. It’s easiest to see this in the “sturm und drang” surrounding the opening of charter schools outside of our urban centers. Though this is cloaked in the rhetoric of local sovereignty, it is more clearly an effort to maintain exclusive access to the specific resource of “public school.”

Princeton, in my adopted state of New Jersey, for instance, is notable for its resistance to the proposed founding of a nearby charter school (despite it, ironically, already having one). Charter schools in the non-urban context break the bundling of housing choice and school choice that so typifies New Jersey (and most states). Keeping this locked pairing in a community like Princeton requires no competition and, yes, residential exclusivity.

Lastly, these families routinely grow the value of their investment by adding more capital to it. In this case they do so in the form of enrichment and other supplemental supports for their children. As a study by Sabino Kornrich at the Juan March Institute in Madrid, and Frank F. Furstenberg showed, in 1972 wealthy families spent five times as much per child as low-income families on enrichment for their children. By 2007 that gap had grown to nine-to-one. Put simply, these families know “what to buy” to accelerate student achievement. And their purchases exacerbate and accelerate the very same gaps a system of free schools is meant to close.

Like anything that’s bought, sold, or increases in value based on scarcity, there are people who don’t have it who want it. The black market for school created when parents lie about their addresses to access better ones is perhaps the best example of this. School districts routinely hire investigators to follow children home when they suspect a child is not a resident to make sure school is not “stolen.” This practice has even been encouraged in popular culture. Indeed, parents “stealing” school, which is ostensibly free, may make the strongest argument that education is, in fact, a consumer good.

I highlight these patterns of school consumption only to draw attention to the reality that, in a space as civic as “public education,” “the market” is alive and well. “School” is routinely purchased and sold, and the families who know this and approach it in this manner get the lion’s share of the benefit. Whether it is right or wrong is a matter for debate. That the strategy works for these families isn’t.