Is 2015 the Year for Universal School Choice?

Everyone likes affirmation. People enjoy being told the project they led was impressive or that their new haircut looks nice or that they made a good choice.

We at the Friedman Foundation are no different. We like to validate others, and we like validation, too. That’s why we are excited to affirm statements from governors’ inaugural addresses in support of universal school choice.

For example, Arizona Gov. Doug Ducey announced, “It will be a first principle of my agenda that schools and choices available to affluent parents must be open to all parents, whatever their means, wherever they live, period.”

In Indiana, Gov. Mike Pence said, “Let’s open more doors of opportunity to more Hoosier families by lifting the cap on the dollar amount that choice schools receive for students and raise the cap on the choice scholarship tax credit program.”

And in Wisconsin, Gov. Scott Walker declared, “We will ensure every child—regardless of background or birthright—has access to a quality education. For many, like my sons and me, it is in a traditional public school. For others, it may be in a charter, a private, a virtual or even a home school environment. Regardless, we will empower families to make the choice that is right for their sons and daughters.”

Those governors aren’t alone in their support for universal school choice.

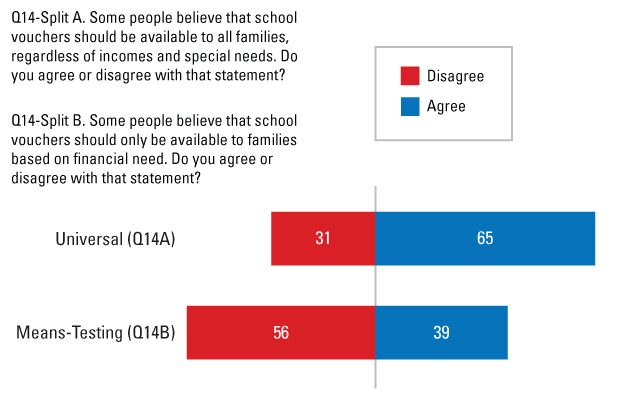

For years, the Friedman Foundation has been administering state and national surveys in which we ask the public whether they support means-tested vouchers or universal vouchers. According to our latest survey in June 2014 (see below), there is far more support for universal vouchers (65 percent support versus 31 percent oppose) than there is for means-tested vouchers (39 percent support versus 56 percent opposed).

Although the questions are worded differently, Education Next’s national survey shows much the same thing. In its poll, 50 percent support the concept of universal vouchers while only 39 percent oppose. The support for universal choice is even higher among African Americans and Hispanics, with 59 percent and 58 percent respectively supporting universal choice. At the same time, the EdNext survey found opposition to means-tested vouchers increased from 45 percent in 2013 to 51 percent in 2014.

The EdNext poll also validates additional questions the Friedman Foundation has been asking for years, this time about school spending and public support.

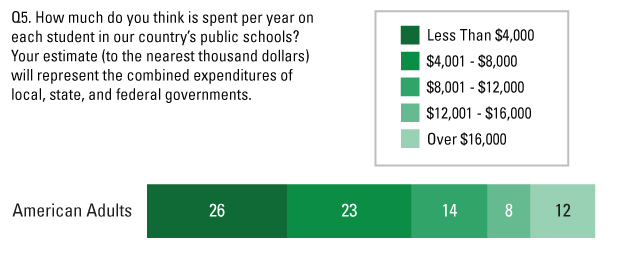

In almost every poll we conduct, we ask the public how much they think is actually spent on education, be it nationally or in their state. Importantly, this is an unaided question, meaning that people tell us what they think the number is without being told. As you can see from the slide below, most have no idea how much we spend to educate children. More than a quarter of Americans (26 percent) believe we spend less than $4,000 per child. Nearly half (49 percent) believe we spend less than $8,000. That’s three quarters of Americans who assume we spend significantly less on public education than what is actually the case.

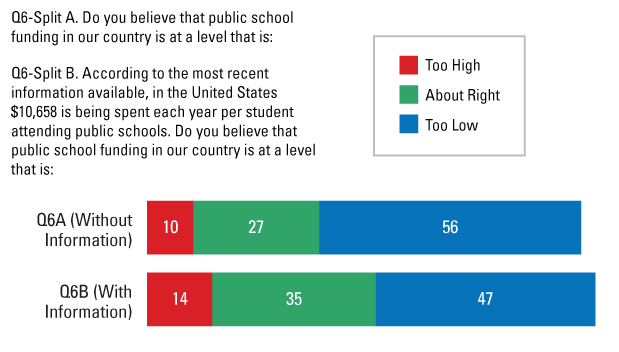

The next follow-up question matters most, however. After people tell us what they think, we share with them how much is actually spent and then ask them whether they think that is too high, too low, or about right.

According to the National Center for Education Statistics, “In 2010, the United States spent $11,826 per full-time-equivalent (FTE) student on elementary and secondary education.” That’s an amount 39 percent higher than the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development’s average of $8,501. (The OECD is a global organization whose mission is “to promote policies that will improve the economic and social well-being of people around the world.”) The most recent information available shows the U.S. spends about $10,658 per pupil in public schools.

And, guess what? When people learn how much is actually spent to educate a child, their opinion changes. The percentage of people who thought education spending was too low dropped to less than half (47 percent).

EdNext’s survey had similar results. In addition to finding that the public has a “misperception of expenditure and salary levels,” it found “when the public is provided with specific information on the current level of expenditure in a local school district, it is less willing to spend more money on schools than when this information is not given.” In fact, support among the public for spending more goes down by almost 20 percent from 60 percent to 43 percent.

These trends show minds can be changed the more we educate families about spending and their educational options (or lack thereof). Why? Americans, especially parents, can plainly see our public education system could be better optimized. Furthermore, they are learning, slowly but surely, that switching to a universal school choice funding system is a policy that will improve the socioeconomic well-being of many more families than our current funding model has.

America’s new and reelected governors will be pressured to spend more money on education rather than pursue school choice. But as our and others’ surveys have found, Americans say we need more of the latter before we pursue the former.