Reasons the Public Education System Has Become Increasingly Centralized

Beyond just the consolidation of America’s school districts I outlined previously, there have been four sizable waves that have eroded public schools’ abilities to differentiate themselves in order to provide real alternatives for consumers of K–12 education. This decrease in educational diversity in the public education system is not consistent with the desires of parents who have a variety of reasons for choosing particular schools for their children.

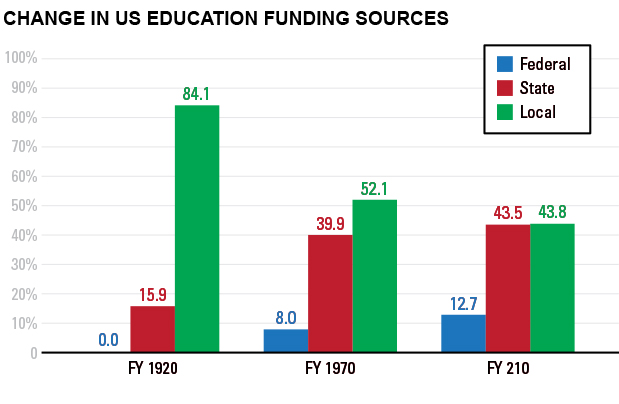

Local, State, and Federal Funding

In a well-intentioned effort to promote equitable funding across school districts and to increase spending per student, especially for historically disadvantaged or disenfranchised students, state governments and the federal government have been providing larger shares of local school district budgets (see table below).

Much of the post-1970 increase in federal funding has been targeted to students with special needs and to federally-mandated state testing and accountability regimes. Increased state funding for the public education system often has been mandated by state courts–or by the threat of costly and protracted litigation–to help equalize funding across school districts.

Of course, the split between state and local taxpayer spending for local public schools varies across states—with some states having significantly higher state shares relative to others. That said, the trend of more centralized spending—and consequent regulation—of “local” public schools is undeniable. Having funding and responsibility coming from multiple levels of government has led to what one commentator termed a kludgocracy, where government-run enterprises become overly complex and therefore incoherent.

No Child Left Behind

The second trend of centralization came from the 2002 federal No Child Left Behind (NCLB) law. The reauthorization of Johnson’s ESEA prompted more federal and state involvement in “local” public schools by increasing federal funding to school districts. That action put more federal strings on those funds, requiring each state to create a common set of English and math standards along with student achievement goals and administer a battery of standardized tests to measure them.

NCLB has led many states to dumb down learning standards and inflate their reported graduation statistics to purportedly meet NCLB’s academic goals. But fixes to the latter have led some states to make it easier for students to obtain a high school diploma, inflating how prepared they really are for college and/or careers. While there was evidence of educators cheating to inflate student test grades before NCLB, this issue has arisen in many school districts in recent years and is largely ignored by states.

Common Core State Standards

The third trend comes from the national move to Common Core State Standards. Although Common Core did not have federal government origins, it has been promoted by the U.S. Department of Education via financial incentives to states prior to its implementation.

Common Core backers want students who transfer from one public school to another—even if the new school is in a different district or state—to be on the same scope and sequence as their prior school. Thus, students would not be ahead in some subjects and behind in others when transferring schools. In addition, students in the public education system would be held to the same high standards regardless of where they went to school. According to supporters, states that adopt Common Core would no longer be able to lower standards to meet testing goals.

One criticism of the Common Core is that all children do not need the exact same timing to meet learning standards or even the exact same learning standards at all, especially in later grades, because children differ in their needs, talents, and interests.

Colleges of Education

The fourth push comes from state requirements to hire only teachers prepared by Colleges of Education. Some education historians say the creation and now ubiquitous nature of Colleges of Education have led to teachers being trained in “progressive” education practices that downplay content knowledge and teacher-directed instruction. In lieu of learning traditional knowledge and skills using textbooks, students construct their own knowledge and engage in experiential learning by doing—often outside the classroom. Teachers who more recently attended Colleges of Education are less likely the “sage on the stage,” but are instead the “guide by the side.” This means these newer teachers are spending less time on direct instruction of students.

Thus, there has been a de-emphasis of traditional academic knowledge and skills and a decrease in the acknowledgement that teachers have a significant reservoir of wisdom, knowledge, and skills, which their students have not yet acquired. Of course, that model is fine if parents chose it for their children, hoping or knowing it works. But all parents should be able to opt-out of this instruction method if they deem it unworthy for their children. Indeed, perhaps these methods have contributed to one in five college freshmen needing remedial coursework.

Although most states have relaxed restrictions on the hiring of teachers prepared outside of Colleges of Education, many school districts are reluctant to hire these “alternative” teachers despite the evidence supporting alternative routes.

These major waves have had some splashes of good outcomes—the ESEA’s recognition of disenfranchised students and NCLB’s spotlight on academic achievement gaps, for example. However, the chief outcome has been moving American education toward a more rigid, more uniform, more regulated, and more bureaucratized system—which has had a deleterious effect on all students, educators, and taxpayers.

In the third and final post in this series, Dr. Scafidi will show the “fruits” of homogenizing the American public school system to date, what education could look like in 25 years if trends persist, and why it’s dangerous.

To read the first post in this series, visit The Decline of “Voting with Your Feet” in American Public School Districts. Read on to the final installment by seeing The Fruits and the Future of Centralization in Public Schools.