Researching the Research on Nine Major Ed Reforms

Are vouchers effective? Do kids need to be in small classes? Are charter schools helping or hurting?

Whether it’s lawmakers debating a new education reform program or journalists framing up a story about a new policy at a local school, there’s one question that always comes up:

What does the research say?

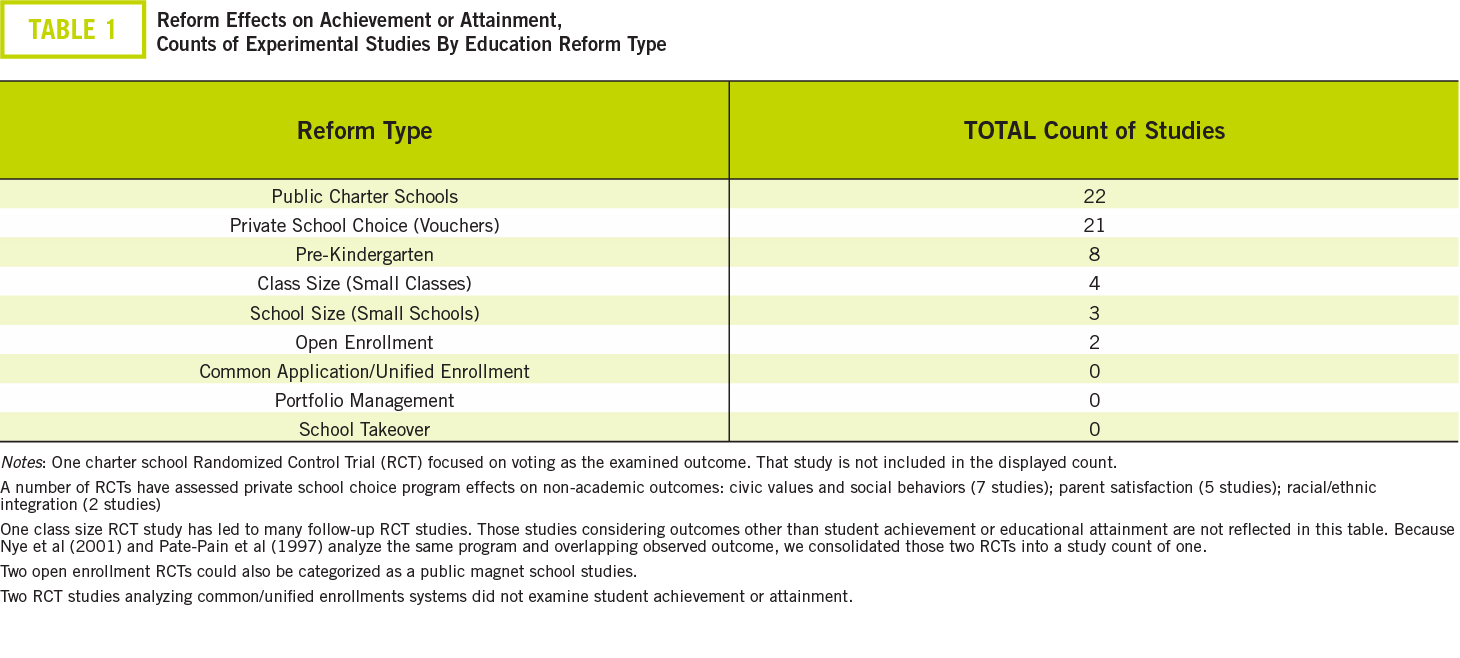

Research is one of our core competencies, so we thought it would be a good idea to find out just how much experimental research has been done in nine major education reform areas focusing on outcomes related to student achievement or education attainment. When we talk about research, we mean the gold standard experimental research, the kind of research that equalizes all the possible variables to determine whether the treatment is actually helping, hurting or having no effect.

We want to be very clear: This review is not intended to pit one reform against the others. What we wanted to do is “research the research” to find out what’s been studied and what hasn’t, so that policymakers and advocates can have a clearer picture on the actual number of experimental research studies by type of education reform.

Here are the nine areas we looked at:

• class size (small classes)

• common enrollment applications/unified

• enrollment systems

• open enrollment (inter-/intra-district)

• portfolio management

• pre-kindergarten

• private school choice

• public charter schools

• school size (small schools)

• school takeover

And here’s what we found:

You can clearly see that vouchers and charters are by far the most researched types of reform where other ideas have been less scrutinized.

It’s important to note that we looked only for randomized control trial (RCT) or random assignment studies to include in this review. Researchers view these “apples-to-apples” comparisons as the best methodology because they conduct experiments with treatment and control comparisons.

When you read the review, you’ll also see that most of the programs that have been studied are at the state level or sometimes only within one city. In part, that’s because states and cities have the freedom to explore new ideas—and control over a majority of K–12 funding.

We bring this up to once again point out that we’re not saying one program or idea is better than another but as a reminder that something that works well in a dense, urban area might not have the same effect in a more rural part of the country. Our conversations about education reform cannot be held in a vacuum; we have to consider the research—and its context.

Of course, you could say this entire project is a bit self-serving. After all, one of our pillars is school choice research, and we always want to see more research done on school choice. But that’s not the only reason we hope this review will spur more studies.

Few people still believe a public school system based on geographic assignment can effectively educate students who have needs based on who they are, not necessarily where they live. The number of ideas that exist to modify and improve that traditional system are truly a reflection of our American innovative spirit.

But we do not have unlimited resources to spend on K-12 education, and we want to be sure that money is doing the greatest good for our students, particularly given the disruption in K–12 education right now. So we must continue to study reforms that already are in place and new ideas as they are introduced. That way, we will be able to answer the question—but what does the research say?—with the best available high-quality data.

For more from the full brief, visit Comparing Ed Reforms.