What to Do About ‘Bad Parents’ in K–12 Education

“This idea of parental choice, that’s great if the parent is well-educated. There are some families that’s perfect for. But to make it available to everyone? No. I think you’re asking for a huge amount of trouble.”

Those are the words of a lawmaker in New Hampshire advocating the repeal of an alternative schooling program that allows students to earn course credit via hands-on experience including jobs and apprenticeships outside the classroom.

It’s a familiar refrain to those of us who believe in educational choice.

Sometimes the judgments are based on the parent’s level of education: If you didn’t finish high school or go to college, how can you guide your own child through the K–12 process?

You can decide for yourself which parents you think didn’t live up to the good parenting standard, but you might want to ask yourself whether you’re judging someone for their choices or their circumstances.

Sometimes it’s a financial attack: Low-income families don’t know how to get themselves out of poverty, so we can’t trust them to make good choices for their kids.

Quite often, critics hide behind words like “engaged” or “involved” when describing the types of parents they believe are qualified—or, conversely, not qualified—to find the best schooling option for their kids.

The underlying message is clear: Because some parents are less educated, have lower incomes or can’t volunteer at the bake sale, they are ‘bad’ parents. They should not be allowed to choose. The system must step in and figure things out for them.

It’s remarkably insulting, and it flies in the face of the fundamental freedoms that define our nation as a place where your starting line doesn’t have to define where you finish.

The Bad Parent Myth

Let’s be clear: There are bad parents out there.

There are parents who abuse, neglect and berate their children. There are parents who pit one child against another. There are parents for whom parenting is a purely selfish pursuit. And there is a long list of systems and organizations in place that aim to help children in abusive and dangerous homes.

But these instances of bad parenting are not defined by income, education or involvement. Rather, they are defined by the parent’s choices.

Let’s revisit the now-familiar tale of Hollywood actresses Lori Loughlin and Felicity Huffman, who pleaded guilty to paying hundreds of thousands of dollars to guarantee their children admission to elite universities.

We can contrast their experience—minimal prison time and a relatively small fine—with the story of Kelley Williams-Bolar, who served nine days in jail in 2011 for using her father’s address to enroll her daughters in a better school district than the one they were assigned to attend. She was on probation for three years and had to complete 80 hours of community service.

All of these moms did wrong—but which ones are the bad parents?

You certainly won’t find this author defending privileged white ladies who cheated the system so their kids could go to fancier schools than they could get into on their own merits. Williams-Bolar, on the other hand, knew her daughters were in a chronically underperforming school district and did what she thought necessary to get them out. (Her act of deception, incidentally, has been memorialized many times in movies and sitcoms.)

You can decide for yourself which parents you think didn’t live up to the good parenting standard, but you might want to ask yourself whether you’re judging someone for their choices or their circumstances.

Also, make sure you’re testing for logical consistency.

If you wouldn’t judge a military spouse for not attending PTA meetings while her wife is deployed, you should think twice before judging a single dad working two jobs to make ends meet for the same sin. Conversely, you can feel more secure judging abusive parents the same whether they shop at Saks or Walmart.

What Do Parents Actually Want

Now that we’ve hopefully cleared up the myth that a parent’s circumstances—income, education and ability to get involved—determine their quality as a parent, we can dive into what we know parents actually want from the K–12 education system based on research.

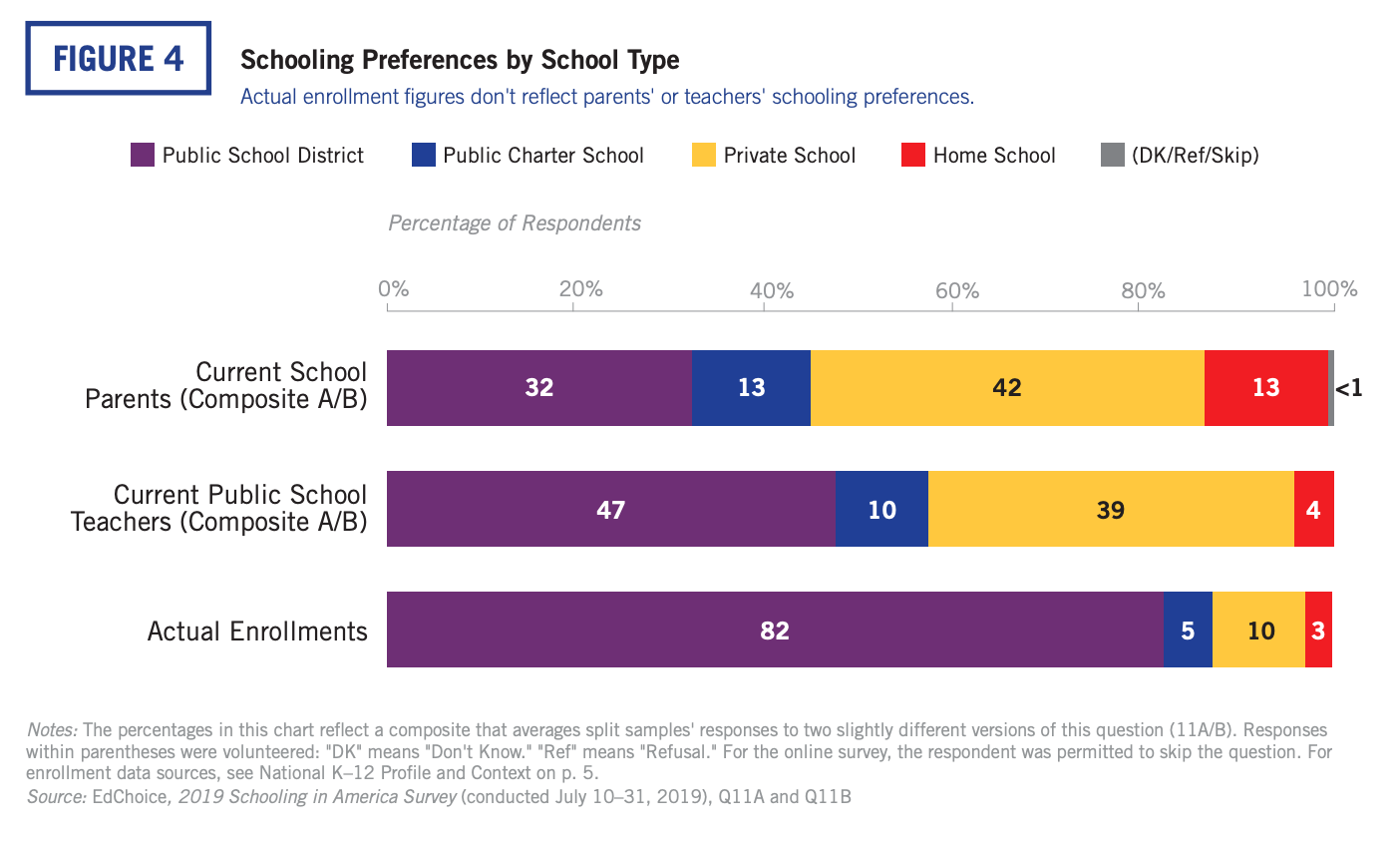

First and foremost, they want something they’re not getting: schooling types beyond the traditional public system. The chart below shows parents of school-aged children, and even public school teachers, would prefer an array of different school settings for their kids, not just their assigned public schools. But when we look at actual enrollment data, we see the majority aren’t getting what they want for their kids.

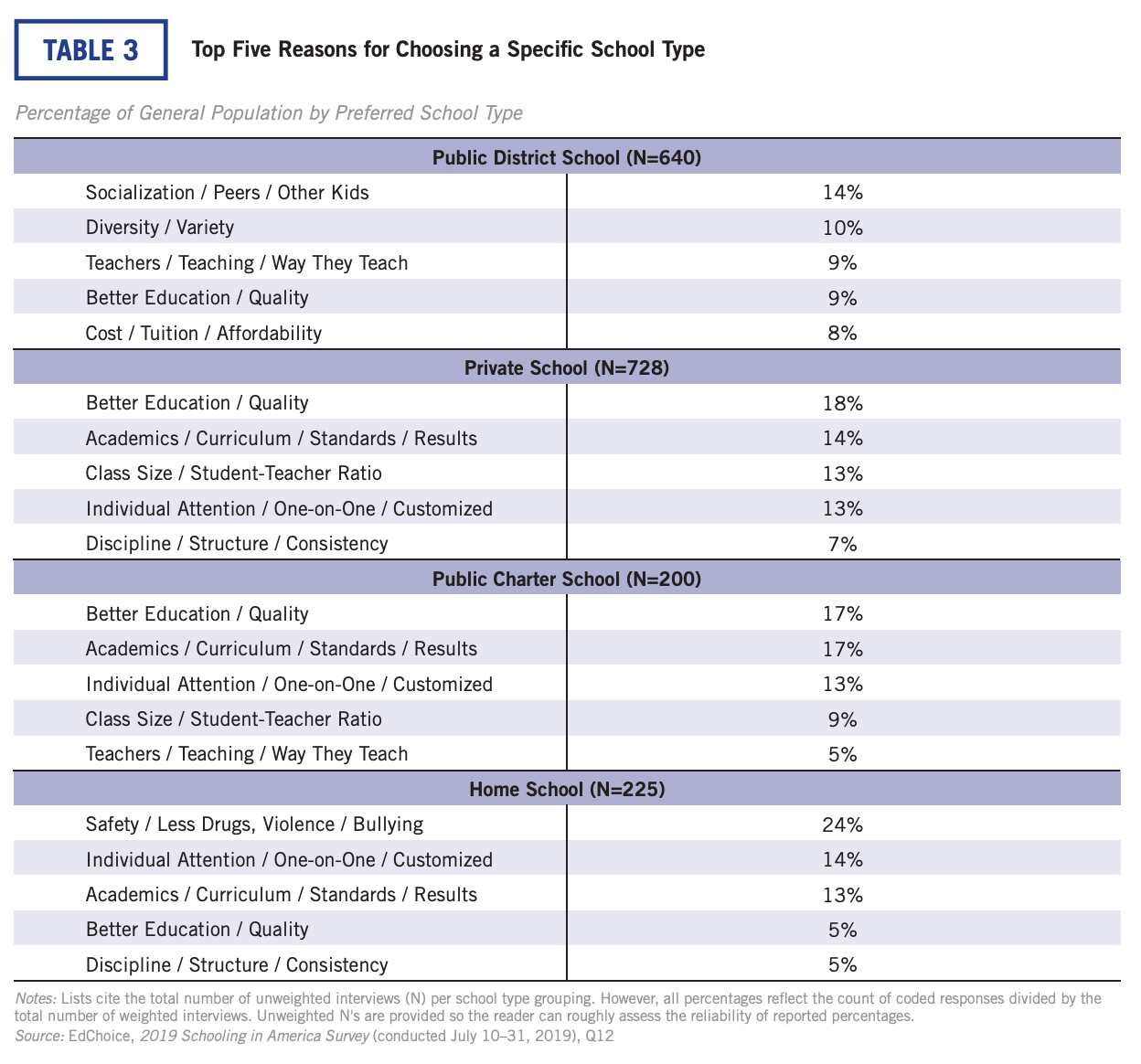

We also know that parents have different reasons for choosing different schooling types.

For instance, parents who choose traditional public schools for their kids prioritize socialization and diversity at higher rates. Parents who choose private schools and charter schools prioritize the quality of education, academic rigor, curriculum, standards and results at higher rates. Parents who choose to home-school their children prioritize safety, individual attention and customized learning at higher rates.

These differing reasons why parents choose the school settings they choose are incredibly important as we chip away at the notion that some parents shouldn’t be allowed to choose at all.

Harvard Law School Professor Elizabeth Bartholet recently caused quite the kerfuffle when she suggested the United States should enact a presumptive ban on home schooling due to a lack of regulation and the possibility students won’t receive an adequate education, exposure to diverse ideas or protection from potential child abuse.

“[Children] have a right to an education that provides them with access to a variety of viewpoints and attitudes, so that when they grow up, they have some genuine autonomy in terms of making their own choices about religion, culture, and employment,” Bartholet said. “Having children exposed to fundamental values in our society, including tolerance for other peoples’ views, is important.”

Had she added “to me” to the end of that sentence, she might have avoided the storm of criticism that befell her following the article’s publication.

Bartholet has her set of beliefs about homeschooling and why people choose to educate their children in that setting. That’s fine. The table above—with responses from actual parents who are homeschooling—tells a different story. Nearly one-fourth of them chose that option for reasons related to safety, drugs, bullying or violence.

Who should we believe?

Conservative writer William F. Buckley once famously said he would “rather be governed by the first 2,000 people in the Boston telephone directory than by the 2,000 people on the faculty of Harvard University.”

But pithiness undercuts the heart of this discussion.

Bartholet absolutely is entitled to her opinion and whatever she would choose for her own family, but it feels awkward not to make room on the debate floor for others who have selected or might select a different option that works better for them.

Your reasons for choosing a school might not be the same as your best friend’s reasons for choosing a school. And that’s okay. We can still be good parents and make different choices for our kids.

The Parental Involvement Myth

Let’s be clear. A highly involved parent does not always equal a “good” parent, but some ways parents get involved in their kids’ schooling has proved to enhance learning for some students.

Even as we acknowledge that not all families choose schools for the same reasons, we likely can find some agreement on shared goals for the K–12 system writ large. We document many of those desired outcomes in our annual review of school choice research, The 123s of School Choice.

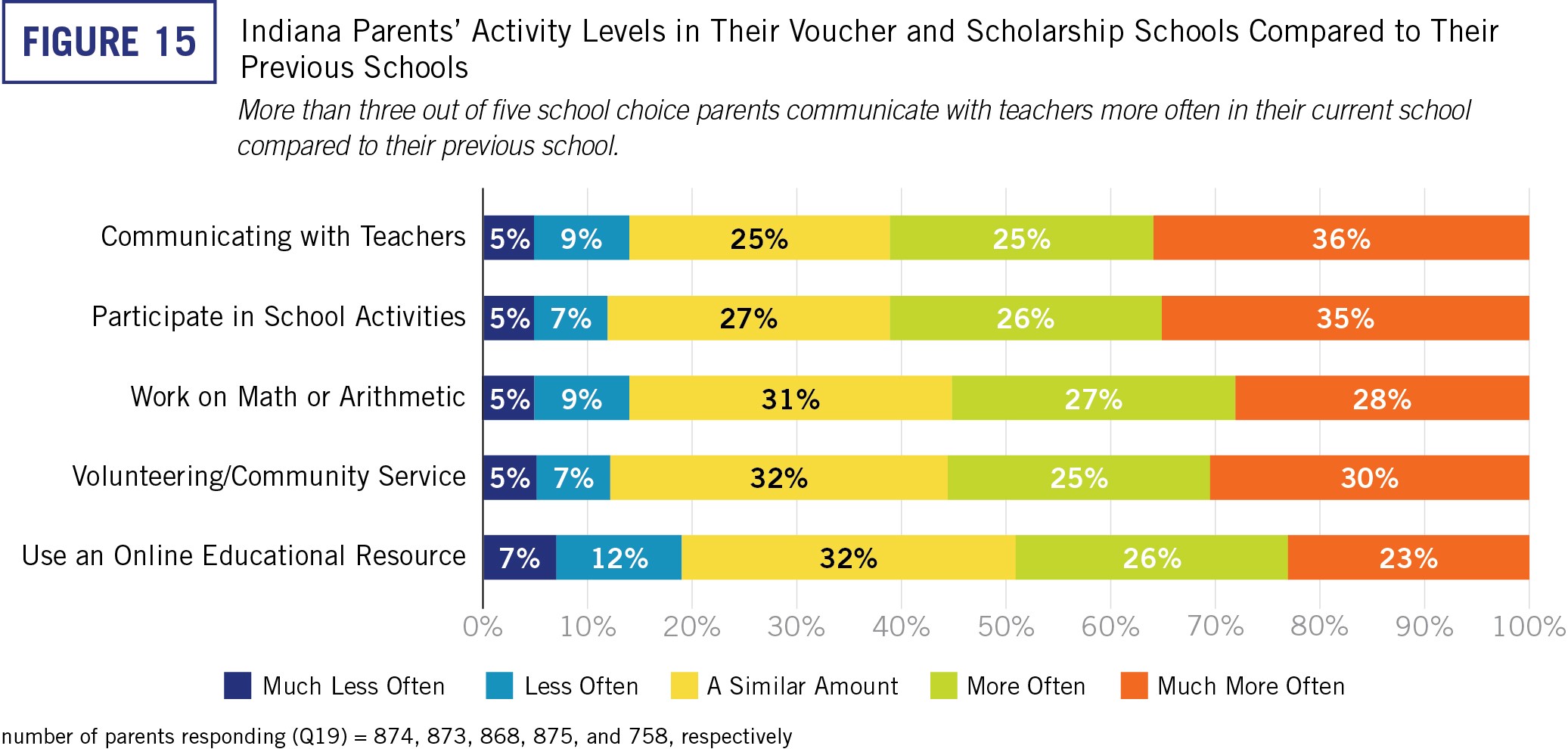

One effect that’s worth noting here is what happens to parents when they are able to gain access to private schools. We asked Indiana parents using private school choice programs how attending a private school changed their school-related activities, and we found out they get way more involved:

Either way, we don’t think parents should be judged for any of this, but for those who believe more involvement equals better parenting, research shows increasing access to private schools is one way to help achieve that goal.

Many scholars have pondered what traditional public schools—that currently educate more than 80 percent of our K–12 students—can do to inspire more involvement among their students’ parents. Too many solutions involve asking parents who simply cannot afford it to sacrifice hours off their paychecks. Not enough solutions involve school leaders learning from school leaders in other sectors who have successfully met parents where they are and fostered a collaborative relationship with them rather than dictating to them.

Bad Parenting: Your Audience Isn’t Who You Think It Is

Parents constantly judge themselves.

Should we force our kids to eat organic food or let them binge on Twinkies while reminding them why their tummies hurt?

Is it worth it to argue endlessly about wearing a coat in cold weather, or should we just let them learn the hard way?

How much “me” time is enough?

Am I being too selfish?

How do I balance work and family?

How do I teach my kids to be good, kind, accepting people but also to voice their opinions and stand up for themselves—and others?

If you can’t figure out the answers, don’t worry. There are literally thousands of blogs and YouTube channels out there dedicated to helping you—further adding to your self-judgment!

Reality check: Parenting is hard. Step-parenting is hard. Foster parenting is hard. Grandparenting is hard. Anyone in a parenting role accepts a tremendous responsibility for growing humans who have limited control over their lives until, suddenly, they have total control over everything. It falls to us to show them, teach them, hold them and love them—and then to let them go.

Whatever you’re doing, odds are you’re doing your best.

Your circumstances might look nothing like someone else’s, but you’re trying, and the kids you’re raising know that. Ultimately, they’re the ones—not your mother-in-law or the PTA president or some professor at Harvard—who get to decide whether you did a good job.