Executive Summary

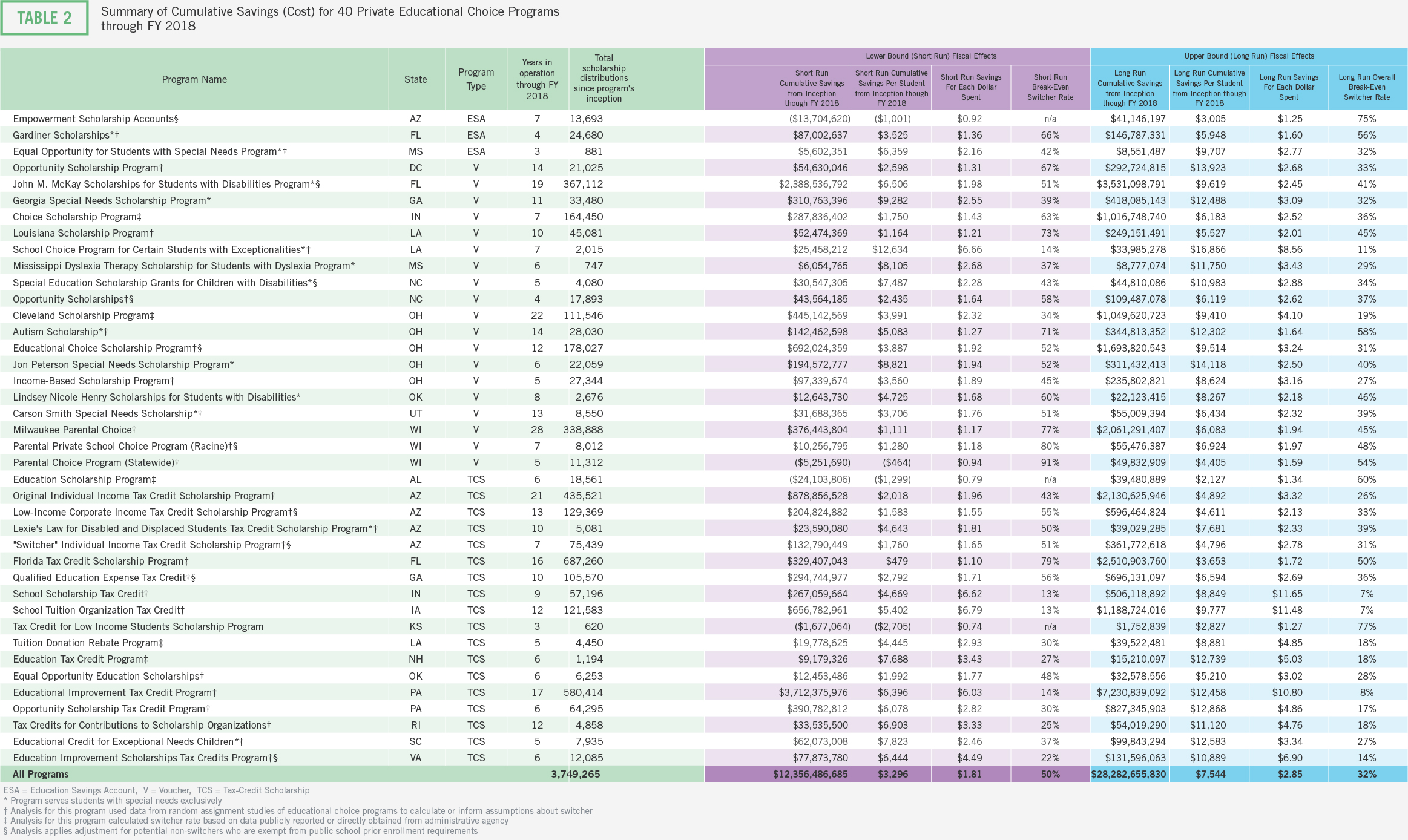

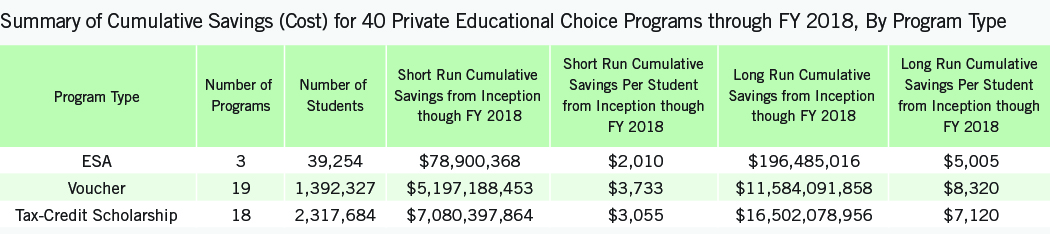

This report summarizes the fiscal effects of educational choice programs across the United States from an analysis of 40 private educational choice programs in 19 states plus D.C. The programs in the analysis include three education savings accounts programs, 19 school voucher programs, and 18 tax-credit scholarship programs.

This study estimates the combined net fiscal effects of each educational choice program on state and local taxpayers through FY 2018—in both the short run and the long run. It uses short-run and long-run variable cost estimates to generate lower bounds and upper bounds of the fiscal effects of educational choice program on taxpayers through FY 2018. The longer a program operates, the closer the savings approach the upper bound (long-run) estimates. The less time a program is in place, the closer its fiscal effects to the lower bound (short-run) estimate. Of the 40 programs in the analysis, four programs in this study were in operation for less than five years while the remaining 36 programs were in operation for at least five years through FY 2018. Thus, for these 36 programs open for five years or more, the fiscal effects of these programs will likely be at or very close to the high-end estimates.

The report also provides context by presenting basic facts about the size and scope of each program, in terms of participation and funding, relative to each state’s public school system. It presents the facts on taxpayer funding disparities between students using the choice programs and their peers in public schools.

Most revenue for K–12 public schools come from state and local sources, and K–12 expenditures comprise a significant share (35.5 percent) of the general fund for all state governments and are a substantial expense for local taxpayers as well.i Given the significant state and local taxpayer funding devoted to children’s education, both citizens and policymakers need to know how school choice programs affect their states’ budgets and the budgets of local public school districts.

Key Findings

Fiscal Effects Estimates

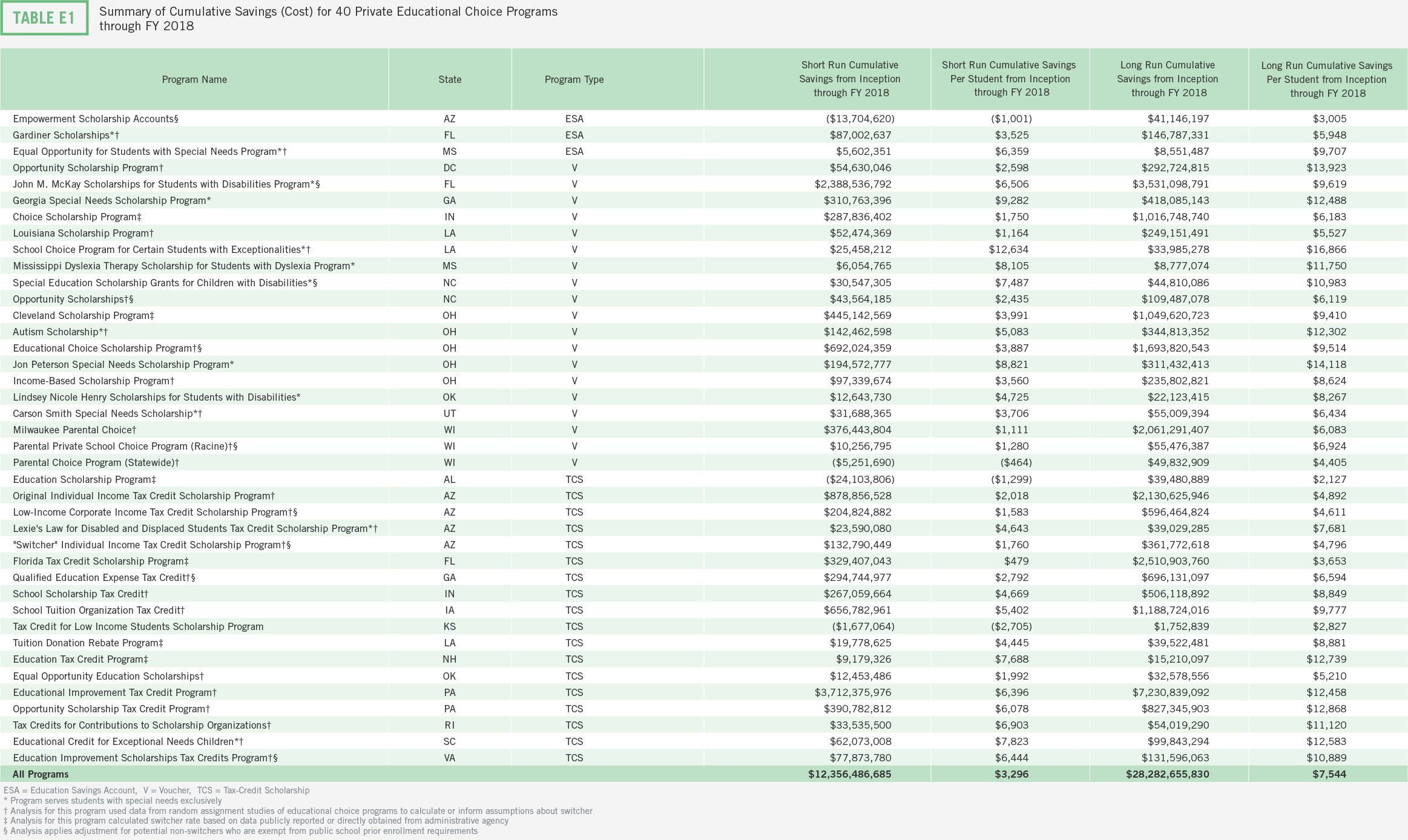

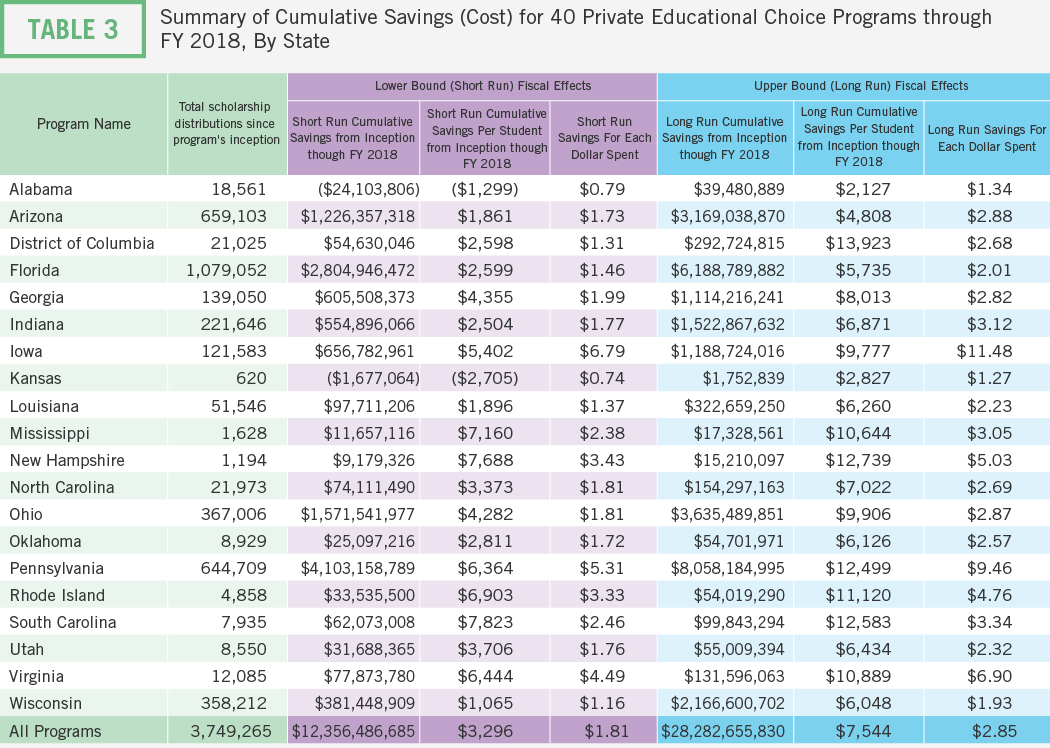

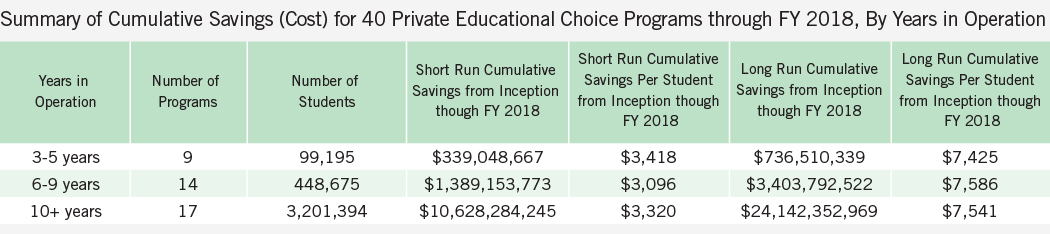

- Through FY 2018, the 40 educational choice programs under study generated an estimated $12.4 billion to $28.3 billion in cumulative net fiscal savings for state and local taxpayers. This range represents $3,300 to $7,500 per student participant. Given that 36 of the 40 programs included in the analysis were in operation for at least five years through FY 2018, the overall cumulative fiscal impact is likely closer to the upper bound estimate of $28.3 billion. (Table ES-1)

- Educational choice programs generated between $1.80 to $2.85 in estimated fiscal savings, on average, for each dollar spent on the programs. These savings result from many of the students who exercised choice who would have been enrolled in a public school if these choice programs did not exist—and enrolled in public schools at a much larger taxpayer cost.

- On average, if at least 50 percent of choice program students switched from public to private schools, these programs saved taxpayer dollars overall. For programs that have been in operation a long time, this break-even rate may be as low as 32 percent. These break-even switcher rates are significantly lower than switcher rates observed in random assignment studies (85 percent to 90 percent, on average) which implies significant savings from choice programs through FY 2018.

Cost Comparisons

Significant public funding disparities exist between public funding for students using educational choice programs and their peers in nearby public school systems.

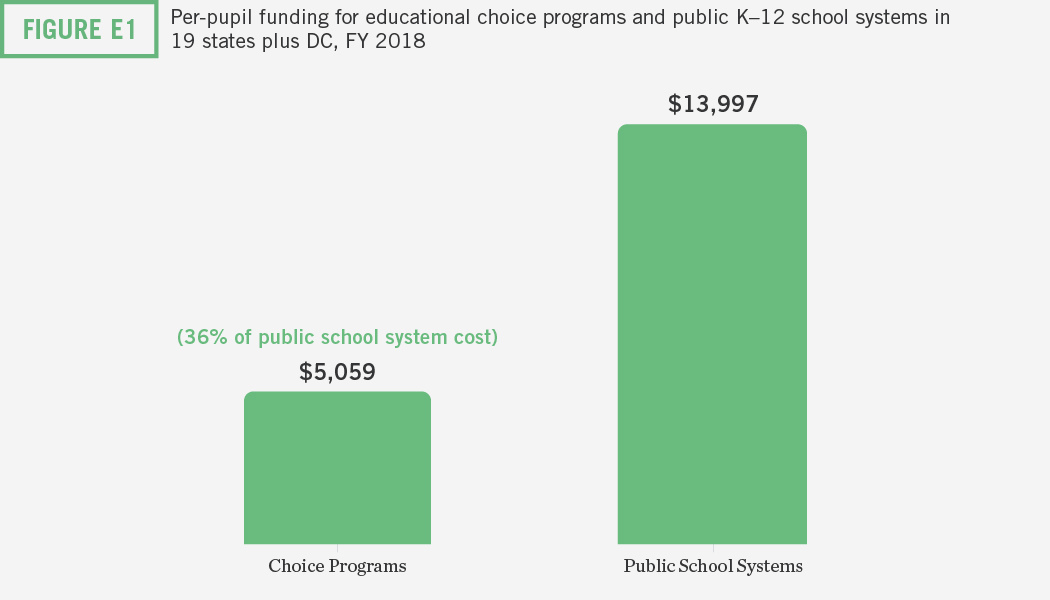

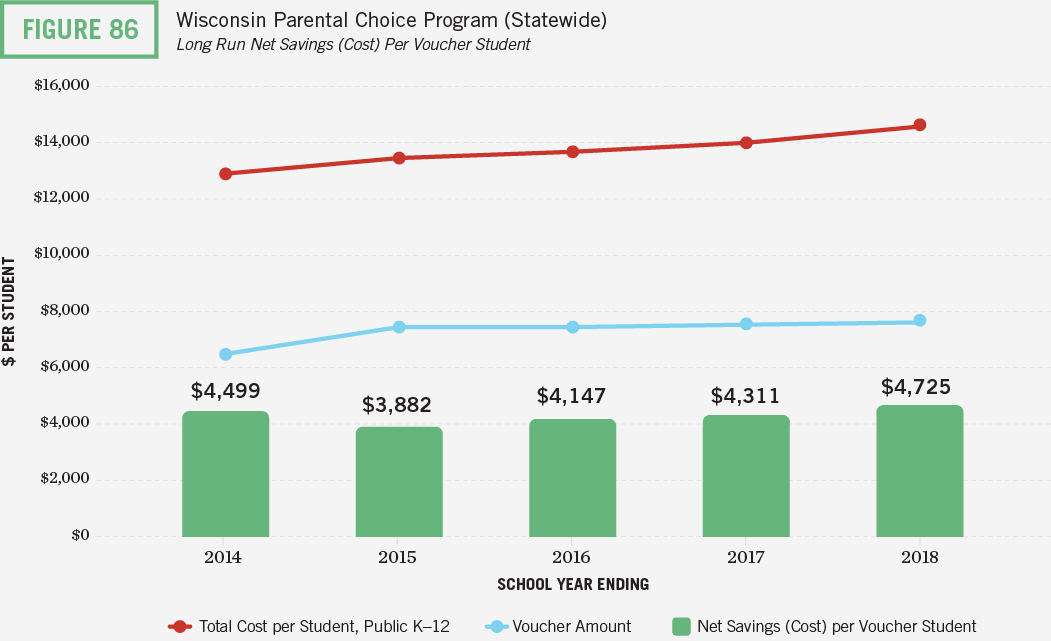

- In FY 2018, the average per-student public cost to support educational choice programs was about $5,000 compared to $14,000 for public K–12 in states where choice programs operate. Thus, students using educational choice programs only received around one-third of the average per-pupil funding amount that their peers received in nearby public school systems in FY 2018. (Figure ES-1)

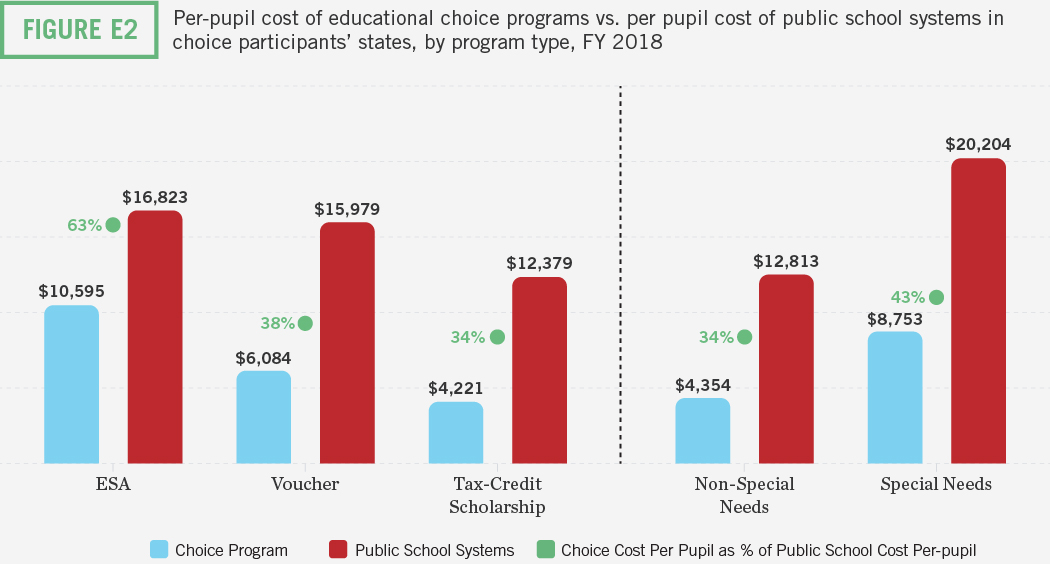

- These funding gaps appear smaller for special needs programs compared to programs for students without special needs. Average per-pupil funding for special needs programs is 57 percent less than average per-pupil funding for public schools while average per-pupil funding for non-special needs programs is 66 percent less than average per-pupil funding for public schools.

- Compared to voucher and tax-credit scholarship programs, these funding gaps are also smaller for ESA programs, which serve mostly students with special needs. (Figure ES-2)

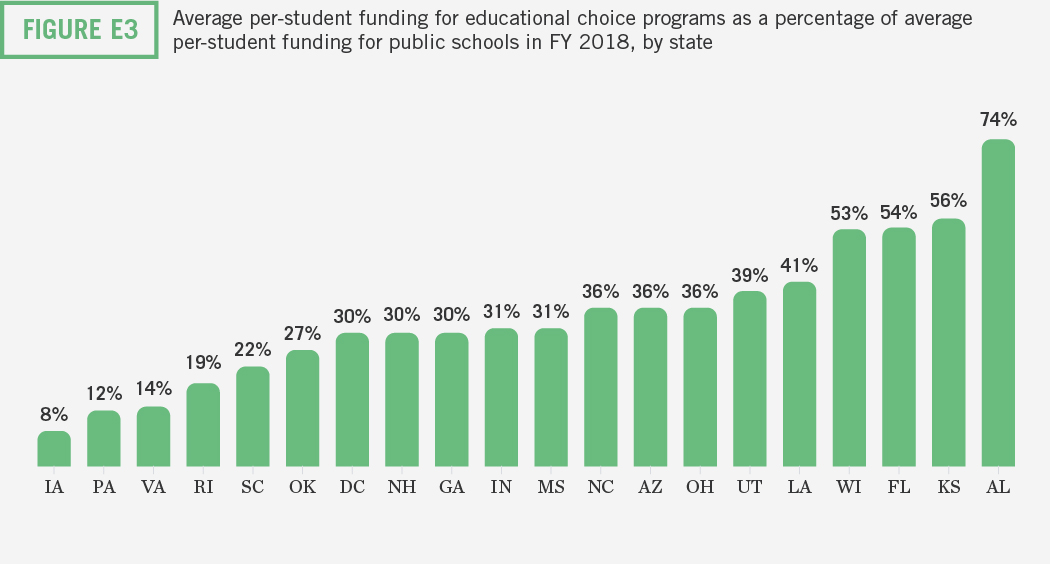

- For 11 of the 19 states plus D.C. in the analysis, students in choice programs received less than one-third of the revenue they would generate for their states’ public schools. For example, students using the D.C. OSP received about 30 percent of the amount that their peers received in nearby public schools.

- For four-fifths of the states plus D.C., students in choice programs received less than half the per-student funding they would generate for public schools. These states enrolled more than 60 percent of students participating in the 40 programs considered during FY 2018. (Figure ES-3)

i National Association of State Budget Officers (2020). 2020 State Expenditure Report: Fiscal Years 2018-2020, retrieved from: https://www.nasbo.org/reports-data/state-expenditure-report

Introduction

School choice critics argue that choice programs drain resources from public schools and therefore harm students who remain in them.1 Because policymakers are tasked with balancing their states’ budgets and ensuring that their public schools meet educational provisions in their states’ constitutions, they are concerned with the fiscal effects of these programs.2

More than two dozen studies have examined educational choice programs’ effects on students enrolling in nearby public schools. Researchers have conducted a handful of systematic reviews of competitive effects research and, more recently, a meta-analysis of this body of research.3 In each of these reviews, researchers conclude that students who remain in district schools after exposure to educational choice programs tend to experience modest educational benefits.4 But the question remains whether educational choice programs lead to higher costs for taxpayers or fewer resources for students who remain in public schools. This report aims to inform conversations about these fiscal issues.

This report summarizes information on the fiscal effects of educational choice programs across the United States. It analyzes 40 educational choice programs in 19 states plus D.C. The programs in the analysis include three education savings accounts programs, 19 school voucher programs, and 18 tax-credit scholarship programs.

- Education savings accounts (ESAs) allow parents to receive a deposit of public funds into government-authorized savings accounts with restricted, but multiple, uses such as private school tuition and fees, online learning programs, private tutoring, community college costs, higher education expenses and other approved customized learning services and materials.

- School vouchers give parents the ability to choose a private school for their children, using all or part of the public funding set aside for their children’s education.

- Tax-credit scholarships allow individual and business taxpayers to receive full or partial tax credits when they donate to nonprofits that provide private school scholarships.5

This study estimates the combined fiscal effects of each educational choice program on state and local taxpayers through FY 2018, including lower bound and upper bound fiscal effects. The information contained in this report is designed to help policymakers and others understand whether educational choice programs have positive, negative, or neutral fiscal effects overall on taxpayers.

The report also presents basic facts about the size and scope of each program, in terms of participation and funding, relative to each state’s public school system. It also presents the facts on public funding disparities between the choice programs and public schools.

Programs Included in Fiscal Analysis

This study uses short-run and long-run variable cost estimates to generate lower bounds and upper bounds on the fiscal effects of educational choice program on taxpayers through FY 2018. The longer a program operates, the closer the savings approach the upper bound estimates. The shorter a program is in place, the closer its fiscal effects to the lower bound. Of the 40 programs in the analysis, four programs in this study were in operation for less than five years while the remaining 36 programs were in operation for at least five years through FY 2018.

Today there are 76 educational choice programs currently operating in 32 states plus Washington, D.C. and Puerto Rico.6 The present analysis examines 40 educational savings account (ESA), school voucher, and tax-credit scholarship programs covering 19 states and D.C from 1990 through 2018. The analysis excludes individual tax-credit and tax deduction programs and town-tuitioning programs. The analysis includes programs with at least three years of data available as the full impact of educational choice programs usually takes time to materialize.7 One-third of programs covered in this report (13) exclusively serve students with special needs. Additionally, more than half of students participating in Arizona’s ESA program are special needs students.

The programs studied include:

1. Alabama’s Education Scholarship Program

2. Arizona’s Empowerment Scholarship Accounts

3. Arizona’s “Switcher” Individual Income Tax Credit Scholarship Program

4. Arizona’s Lexie’s Law for Disabled and Displaced Students Tax Credit Scholarship Program

5. Arizona’s Low-Income Corporate Income Tax Credit Scholarship Program

6. Arizona’s Original Individual Income Tax Credit Scholarship Program

7. D.C.’s Opportunity Scholarship Program

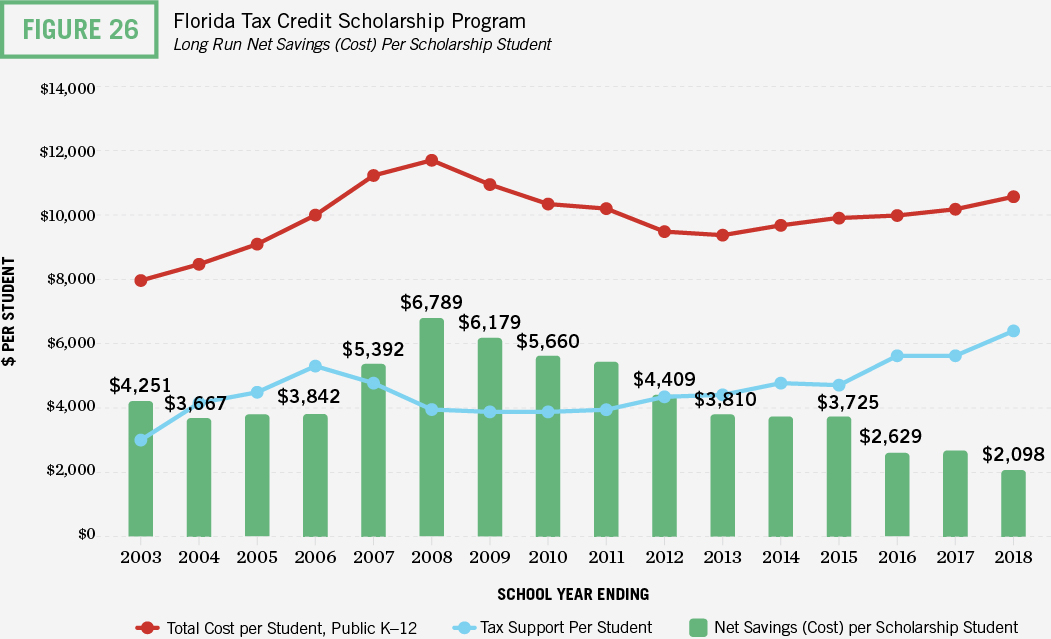

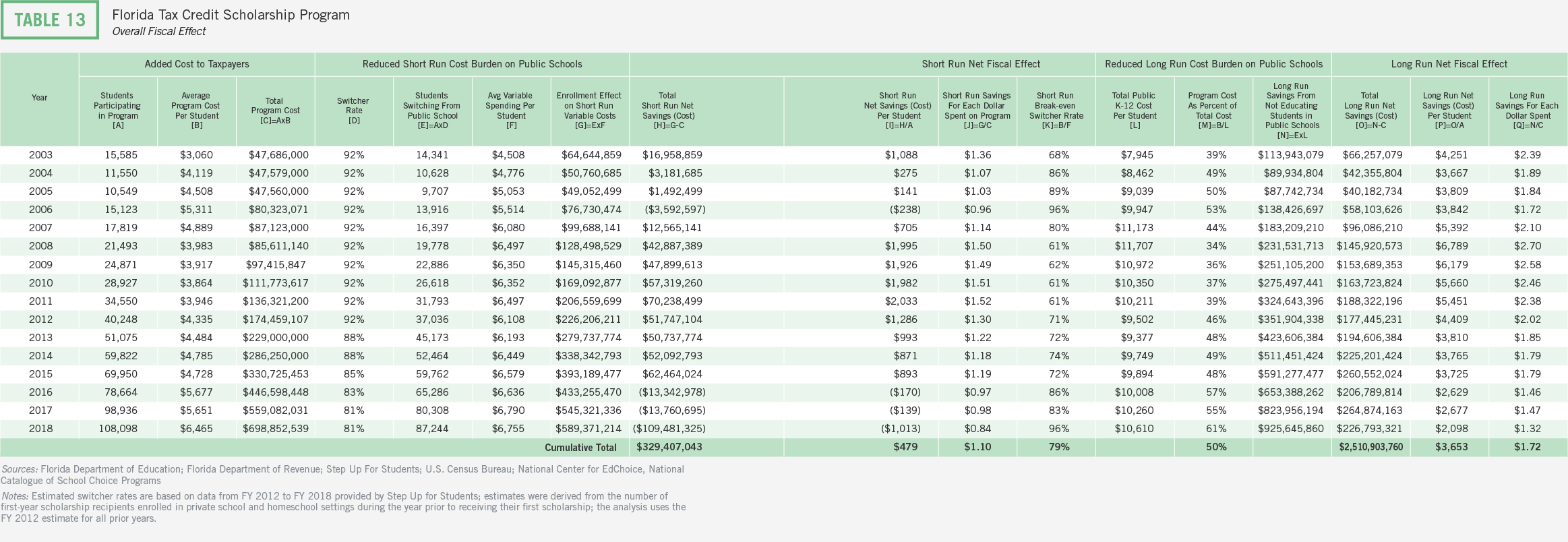

8. Florida Tax Credit Scholarship Program

9. Florida’s Gardiner Scholarships

10. Florida’s John M. McKay Scholarships for Students with Disabilities Program

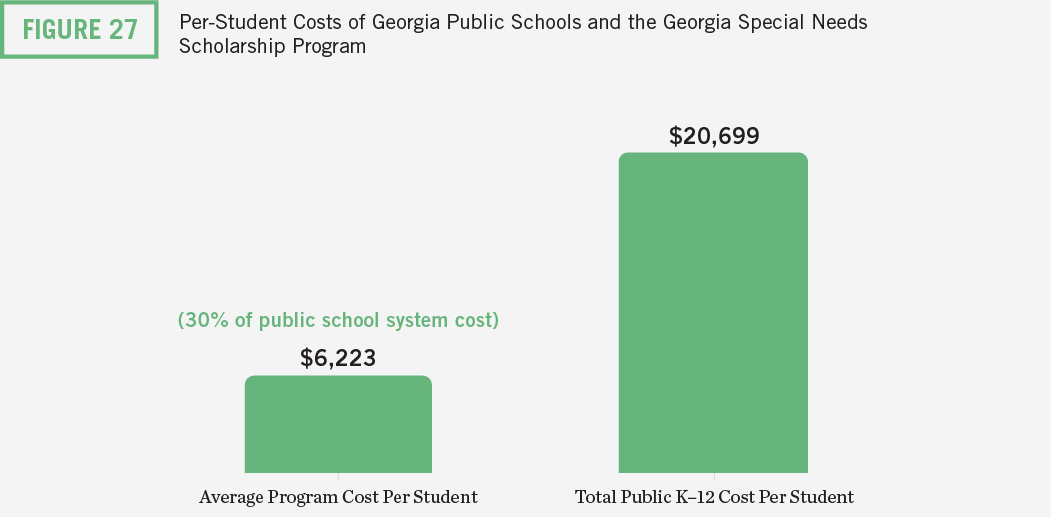

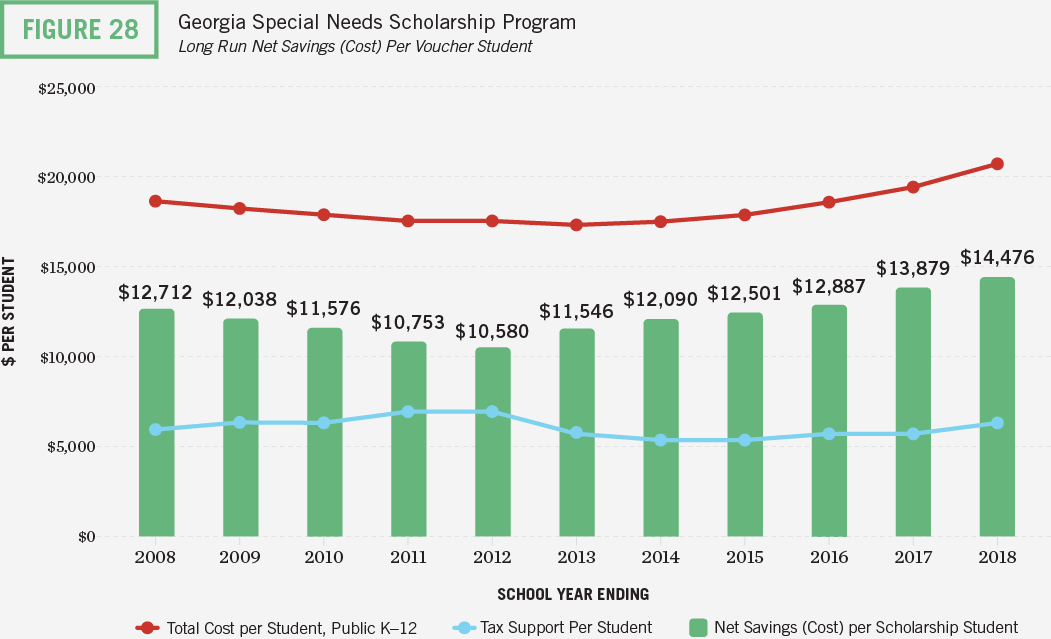

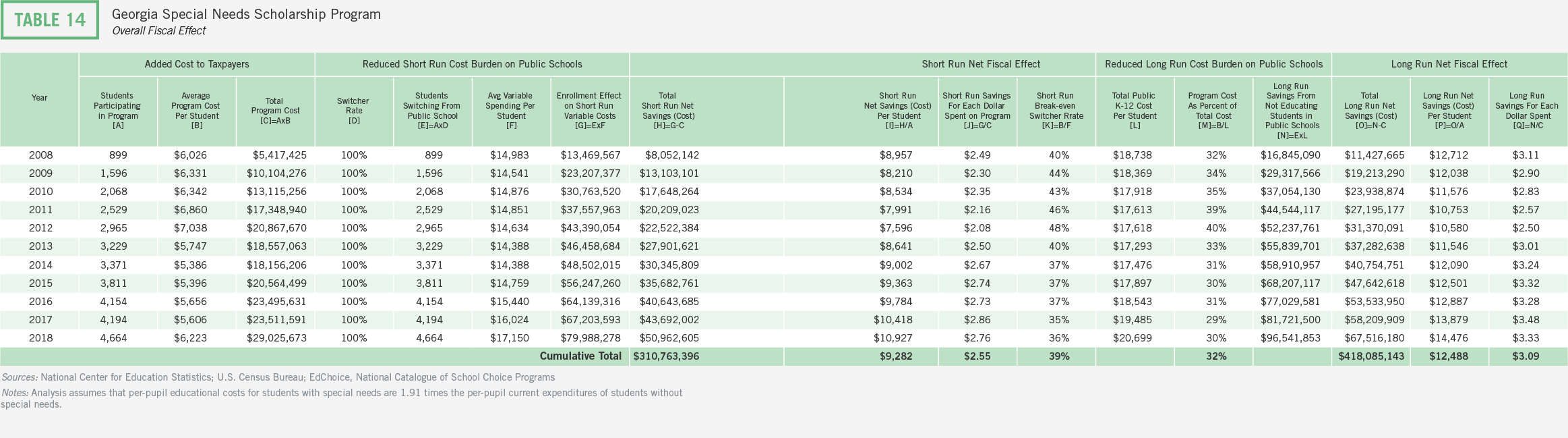

11. Georgia Special Needs Scholarship Program

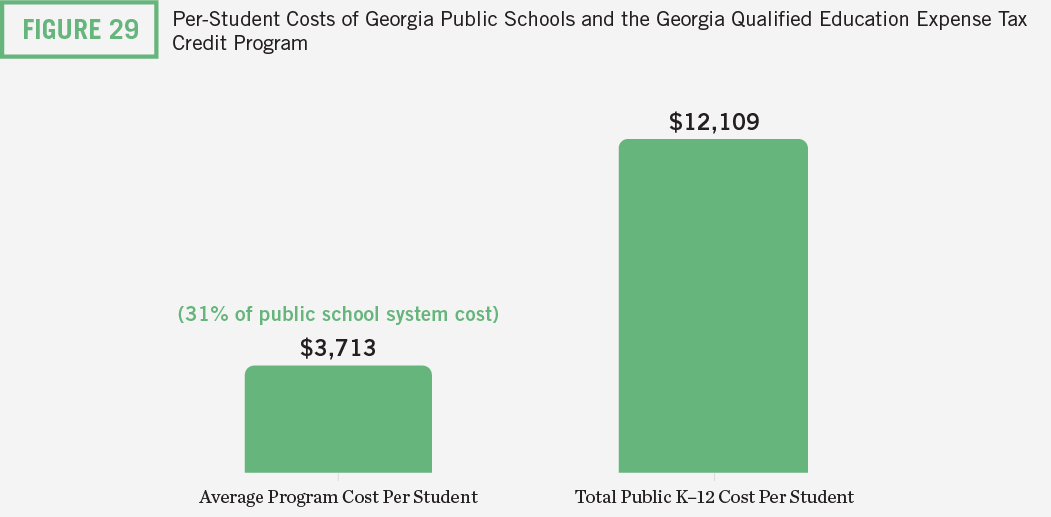

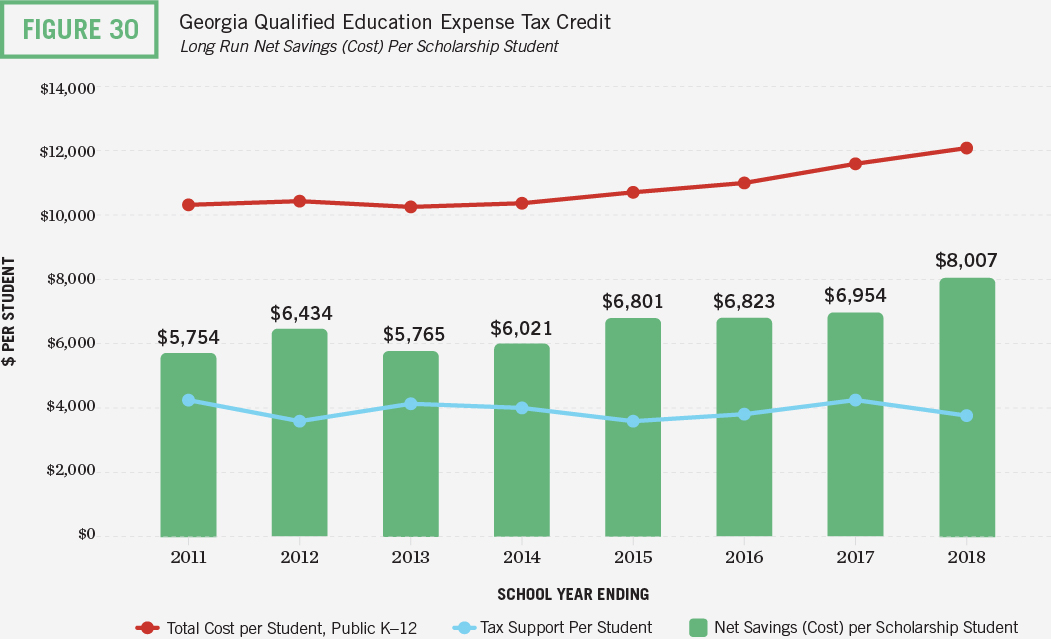

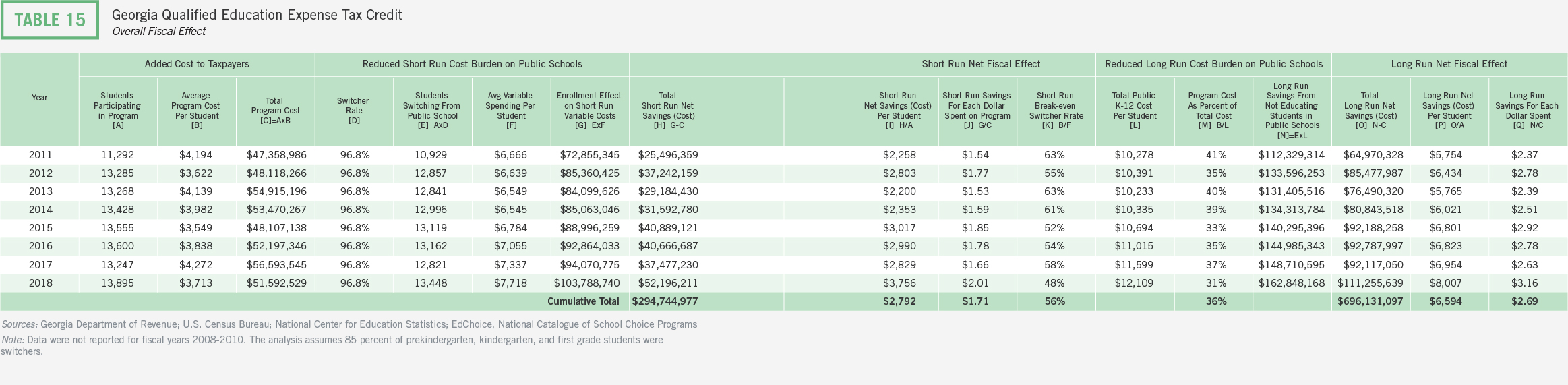

12. Georgia’s Qualified Education Expense Tax Credit

13. Indiana’s Choice Scholarship Program

14. Indiana’s School Scholarship Tax Credit

15. Iowa’s School Tuition Organization Tax Credit

16. Kansas’s Tax Credit for Low Income Students Scholarship Program

17. Louisiana Scholarship Program

18. Louisiana’s School Choice Program for Certain Students with Exceptionalities

19. Louisiana’s Tuition Donation Rebate Program

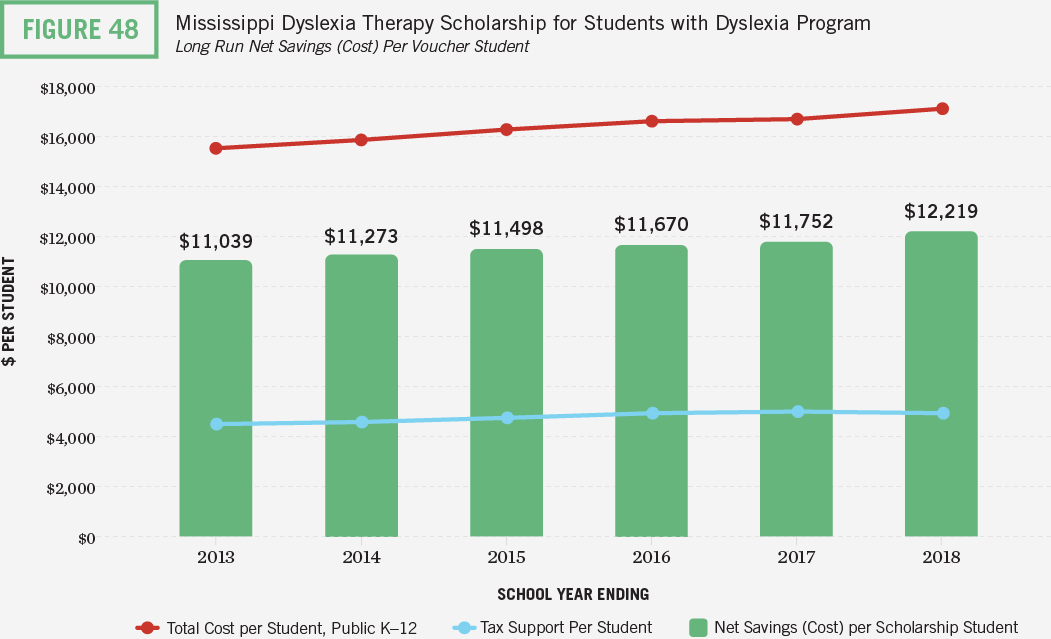

20. Mississippi Dyslexia Therapy Scholarship for Students with Dyslexia Program

21. Mississippi’s Equal Opportunity for Students with Special Needs Program

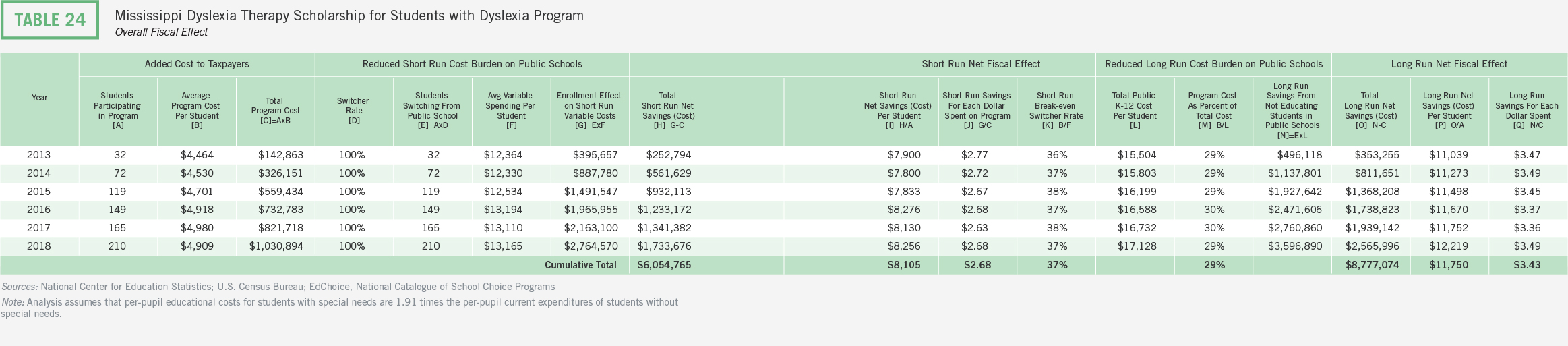

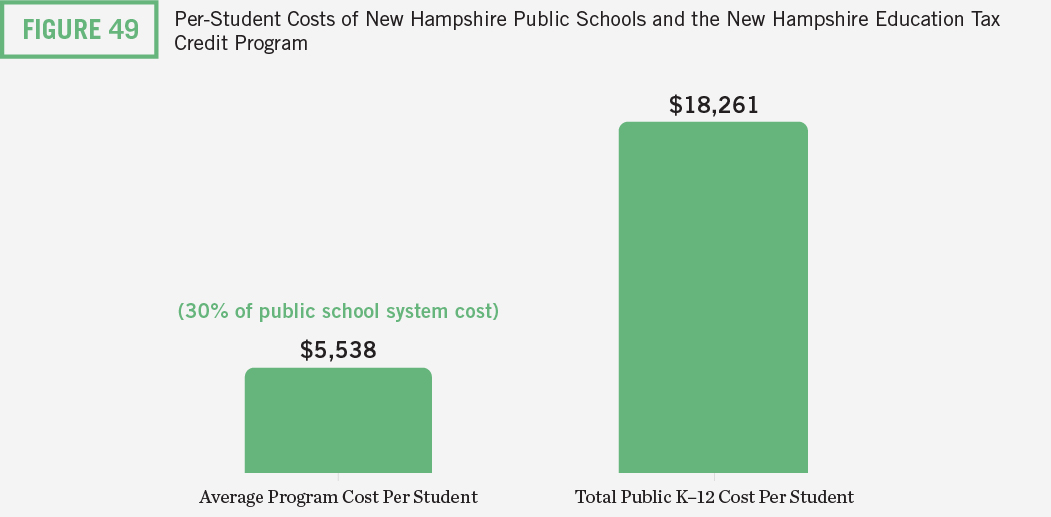

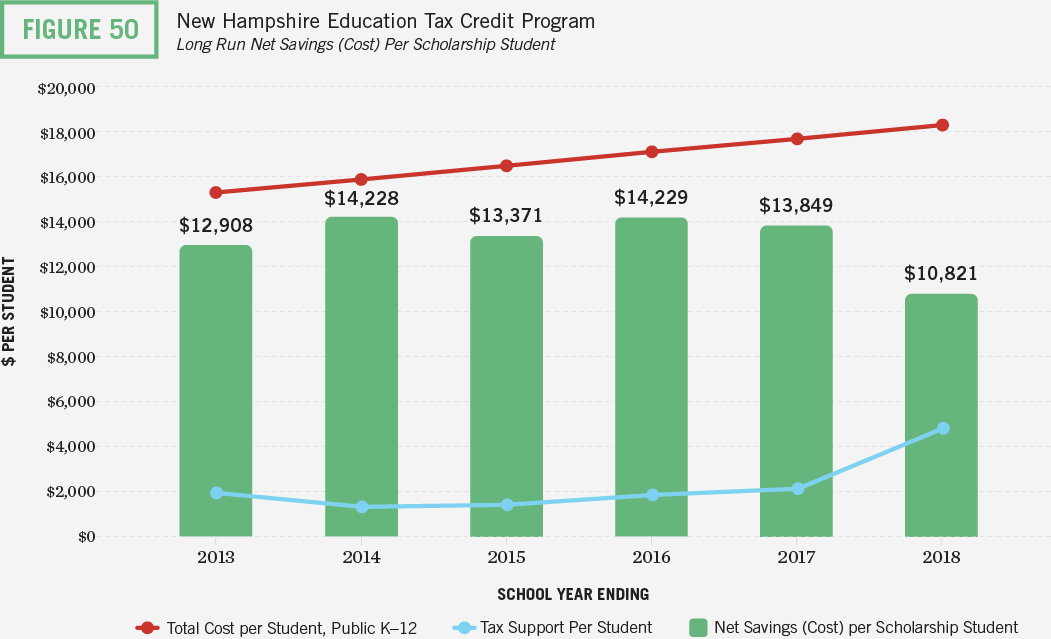

22. New Hampshire’s Education Tax Credit Program

23. North Carolina’s Opportunity Scholarships

24. North Carolina’s Special Education Scholarship Grants for Children with Disabilities

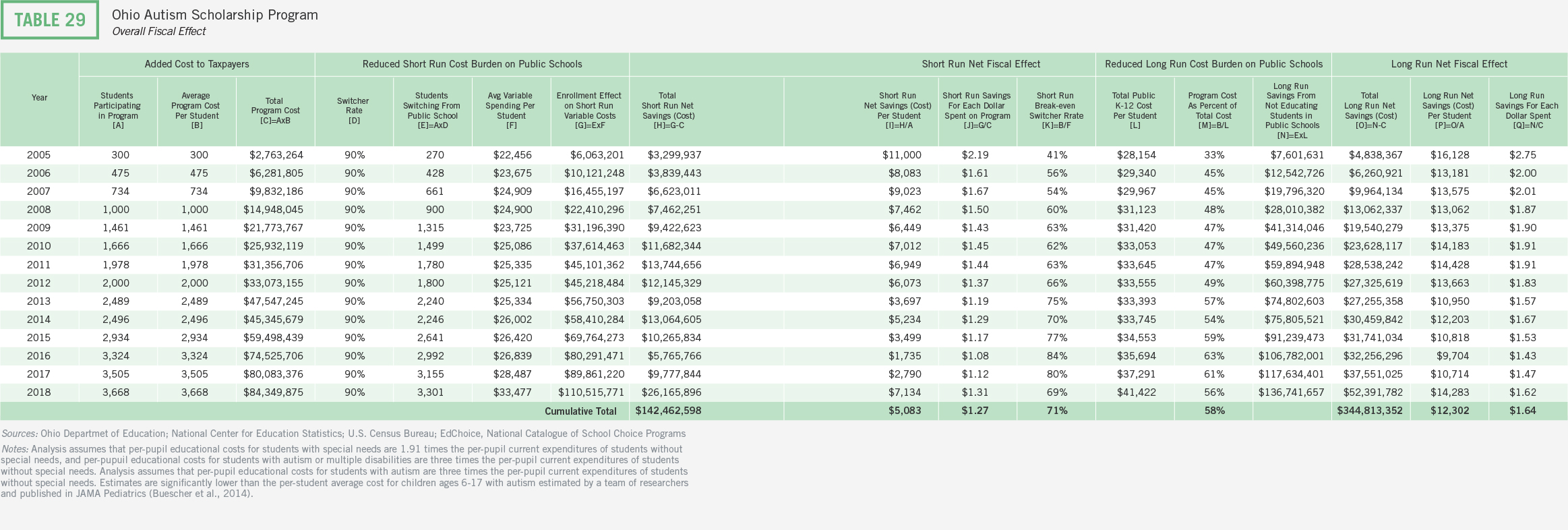

25. Ohio’s Autism Scholarship

26. Ohio’s Cleveland Scholarship Program

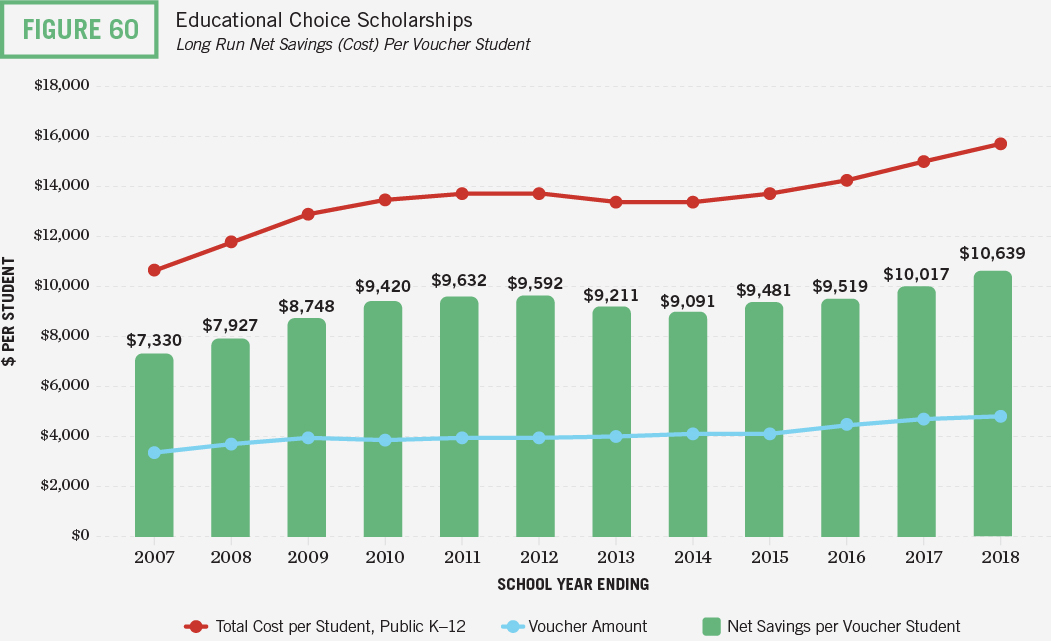

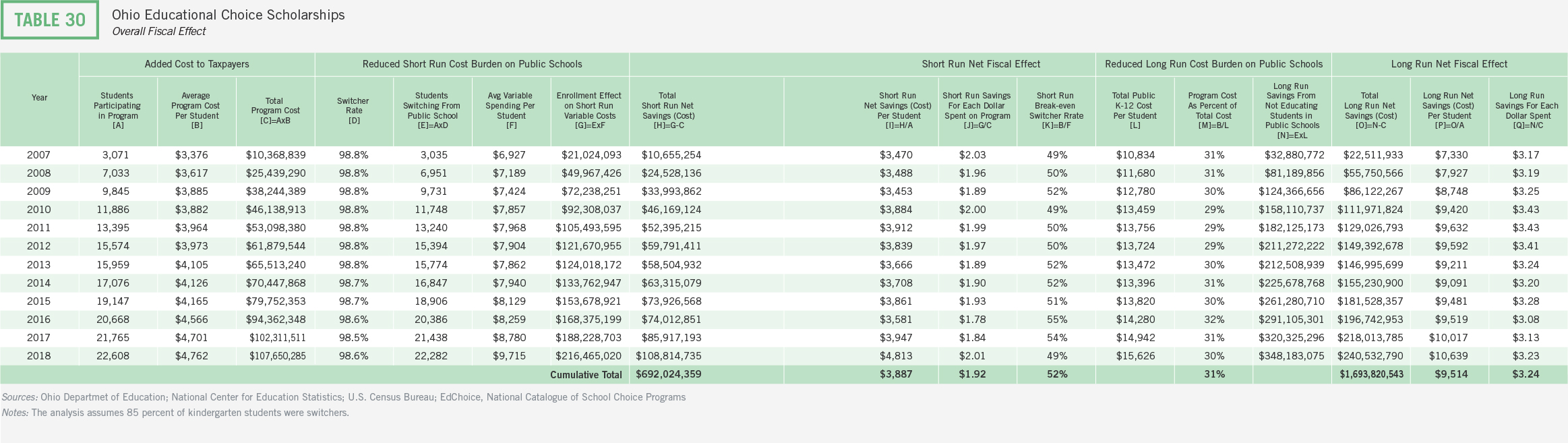

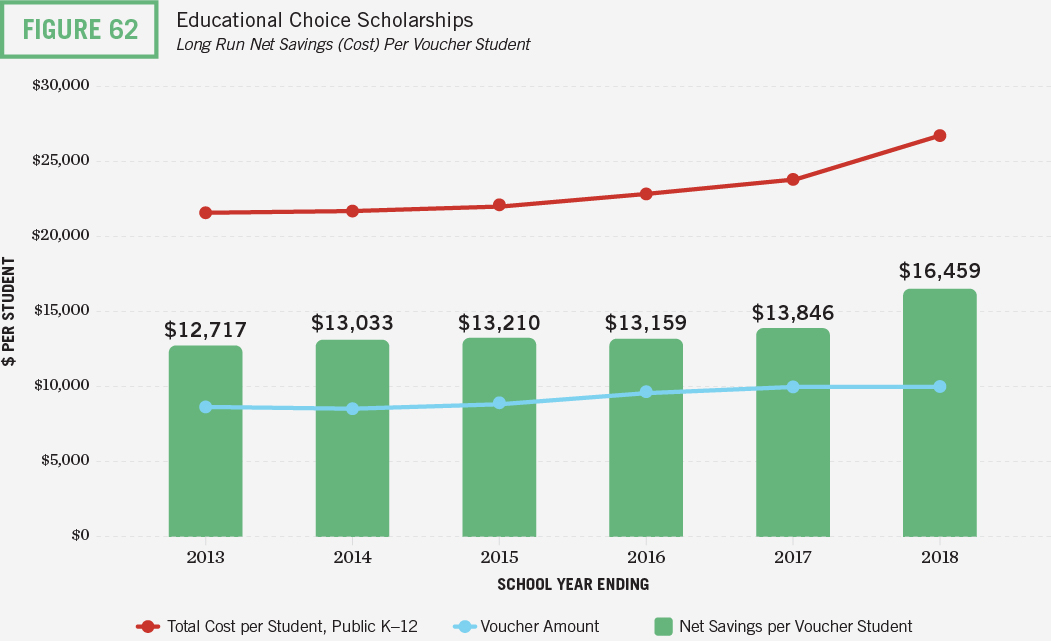

27. Ohio’s Educational Choice Scholarship Program

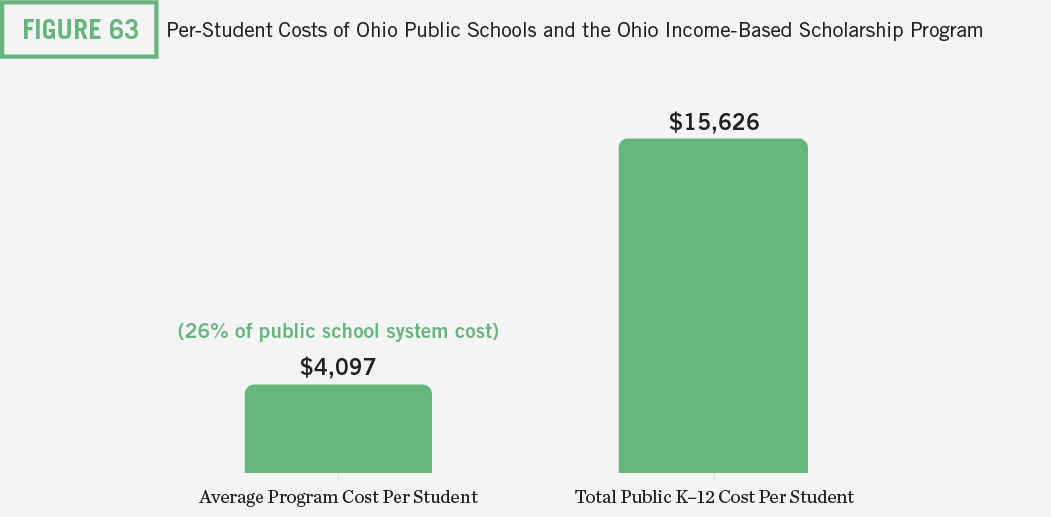

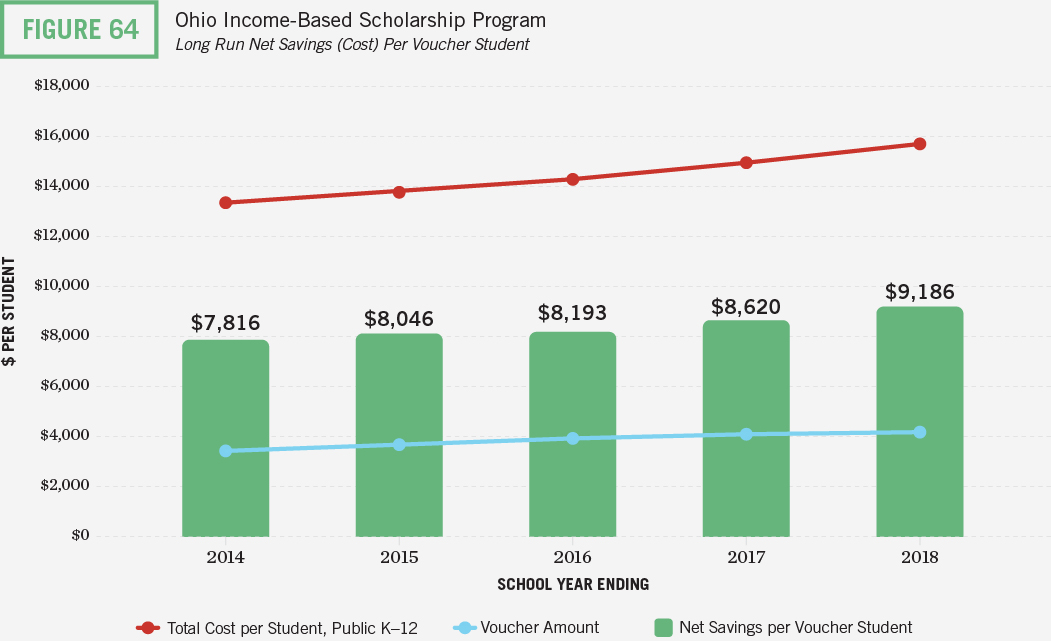

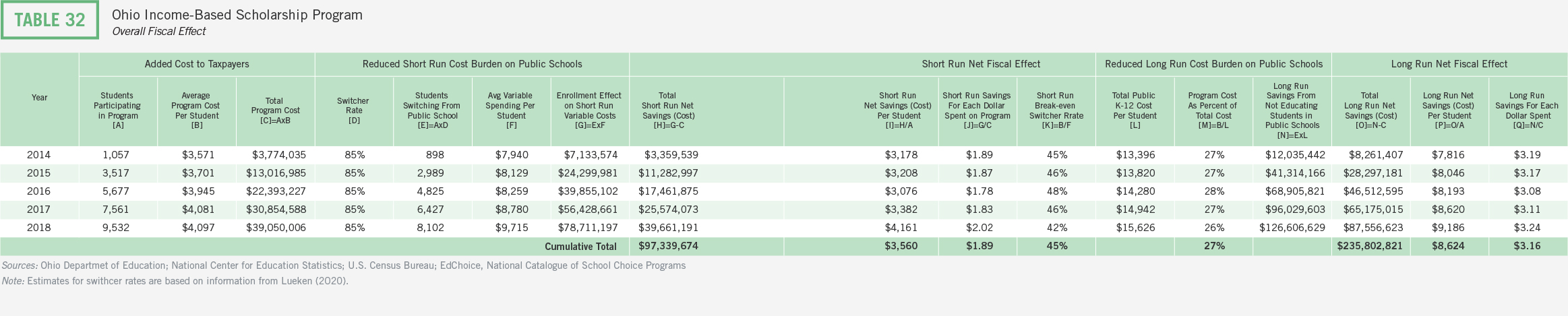

28. Ohio’s Income-Based Scholarship Program

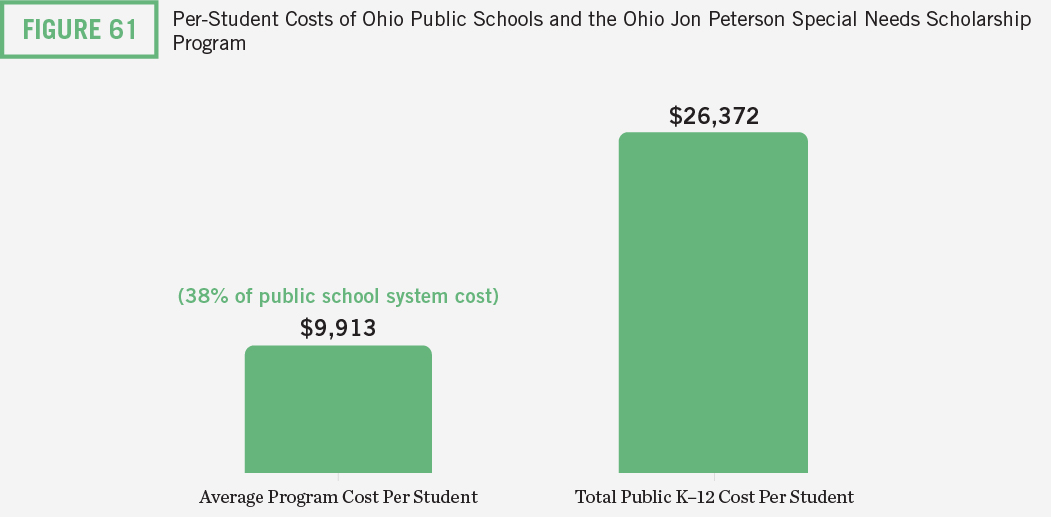

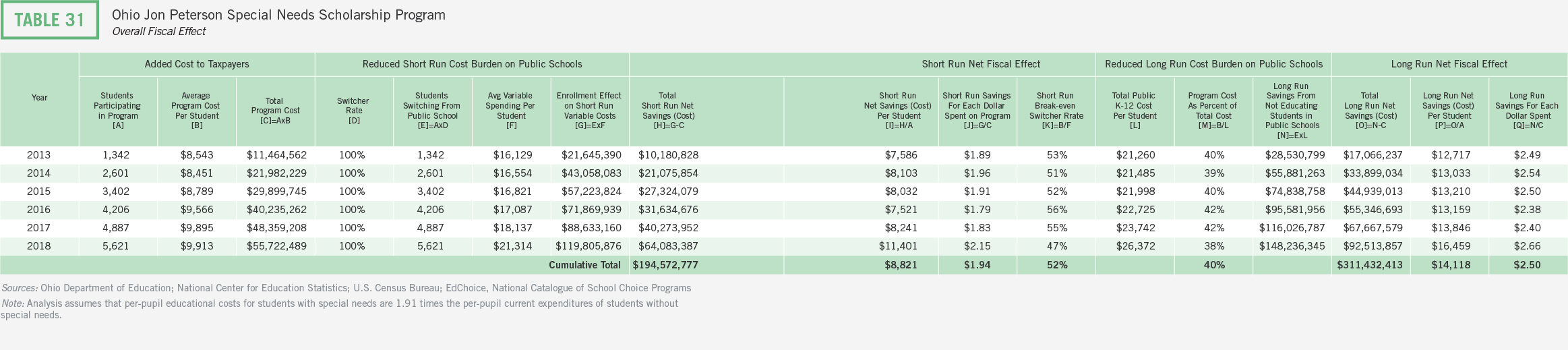

29. Ohio’s Jon Peterson Special Needs Scholarship Program

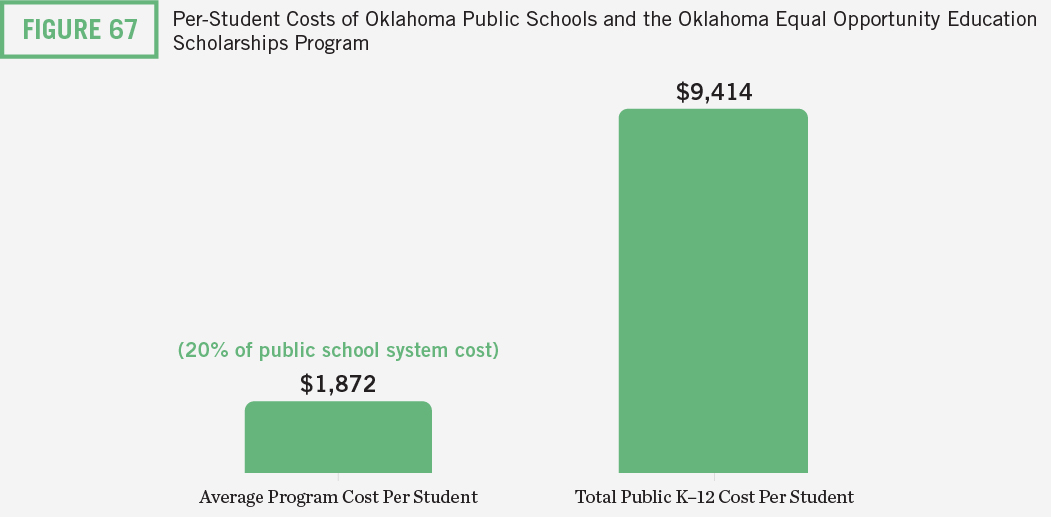

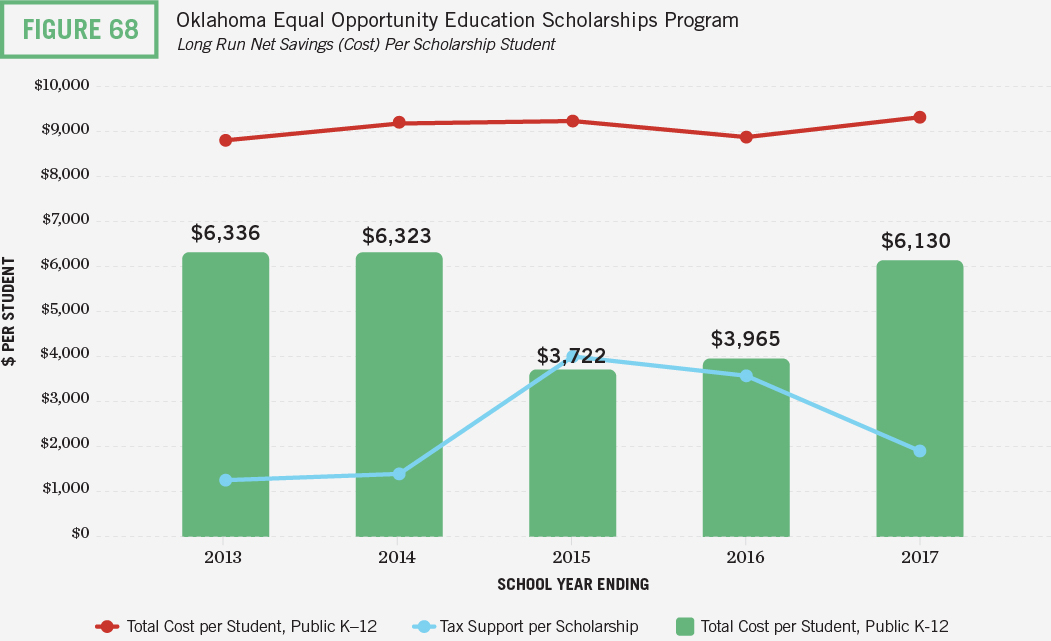

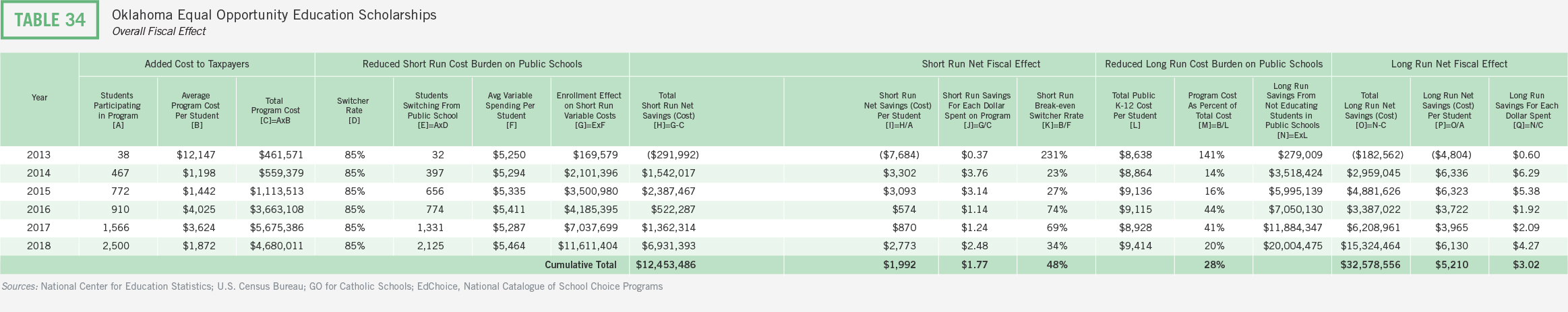

30. Oklahoma’s Equal Opportunity Education Scholarships

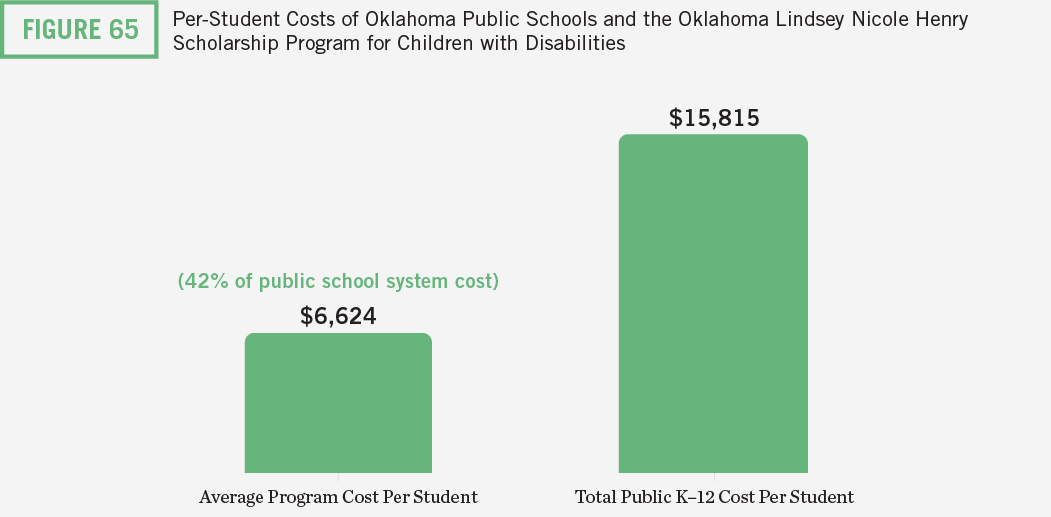

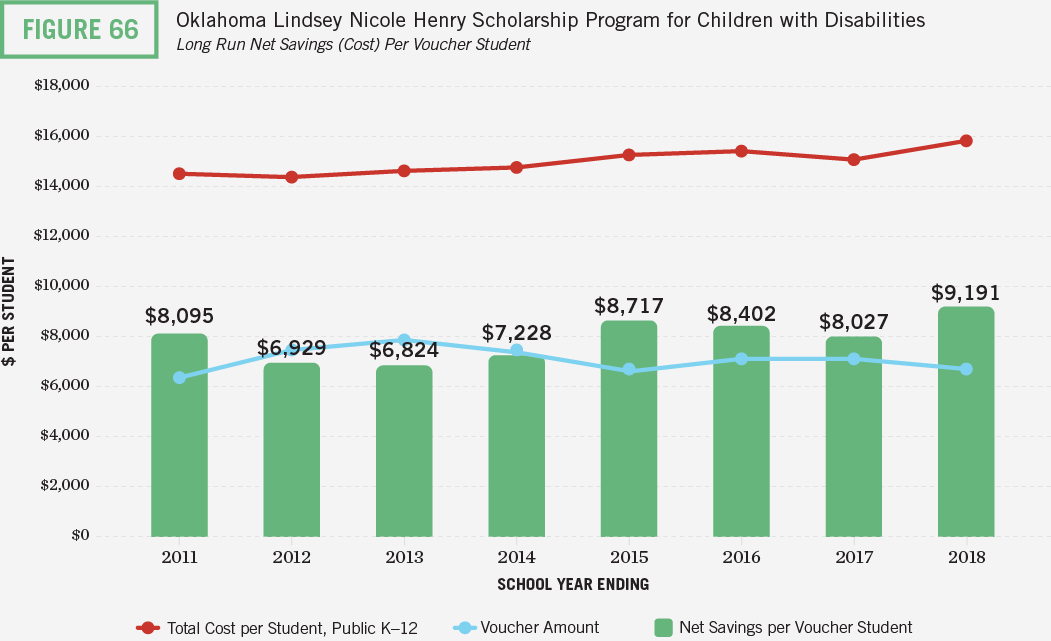

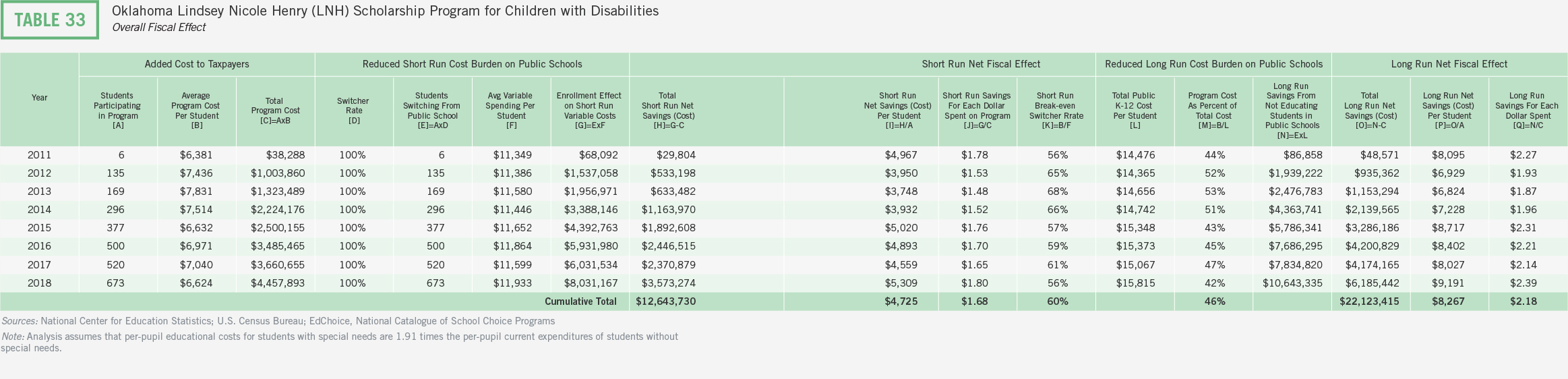

31. Oklahoma’s Lindsey Nicole Henry Scholarships for Students with Disabilities

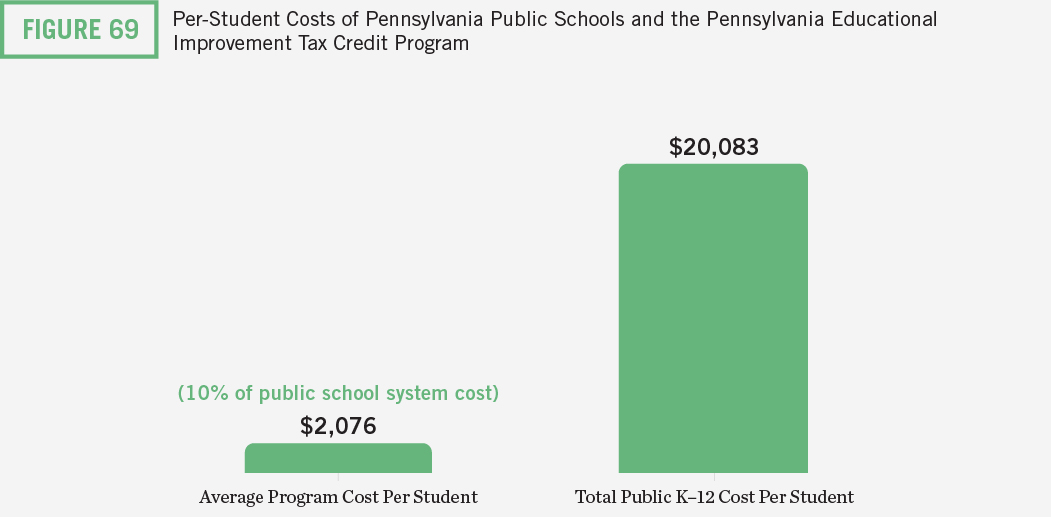

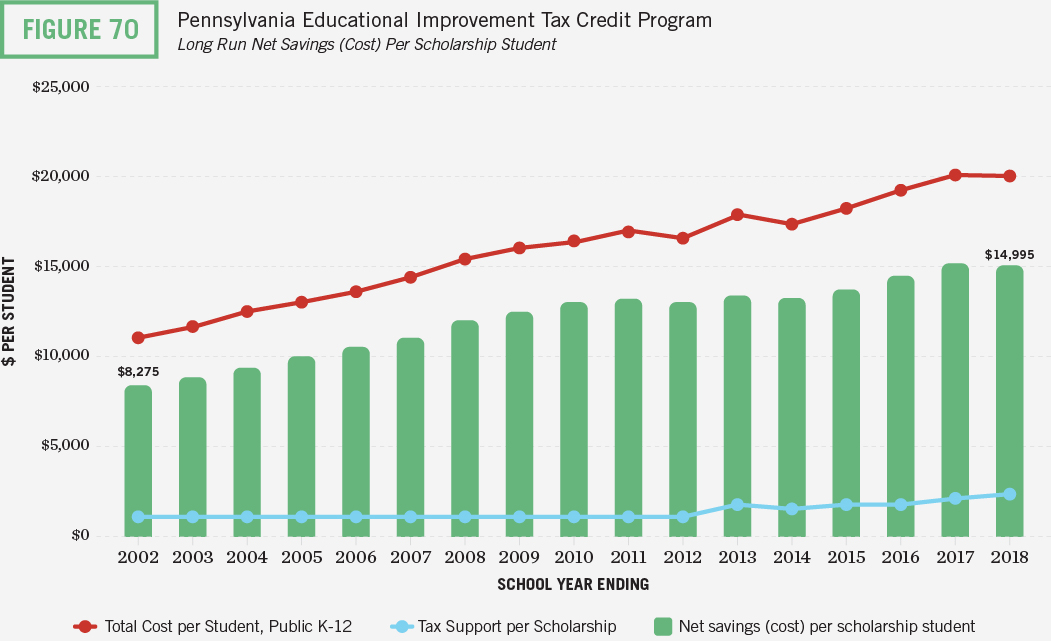

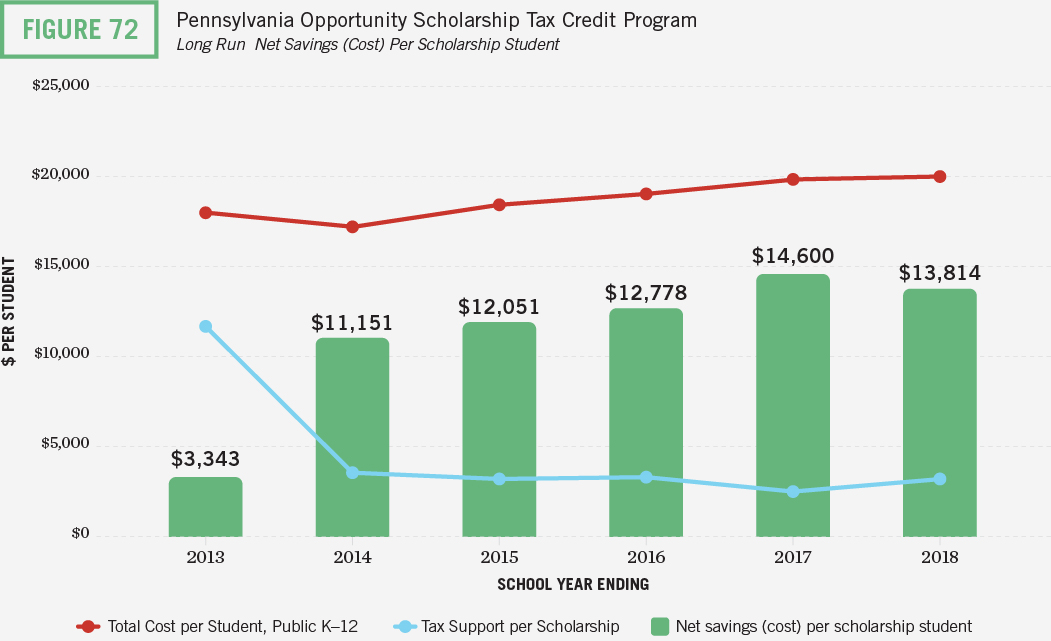

32. Pennsylvania’s Educational Improvement Tax Credit Program

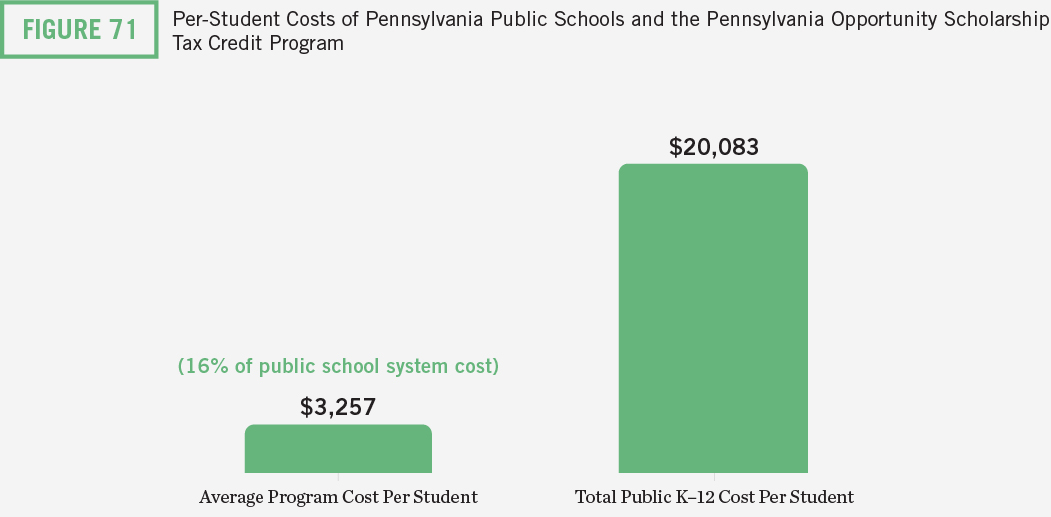

33. Pennsylvania’s Opportunity Scholarship Tax Credit Program

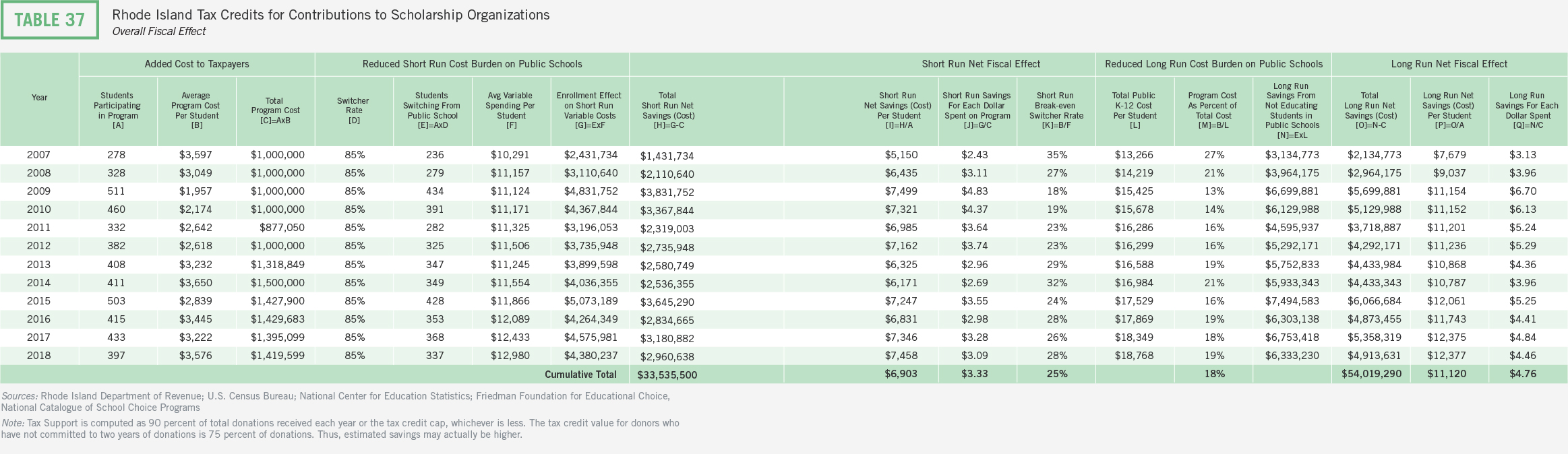

34. Rhode Island’s Tax Credits for Contributions to Scholarship Organizations

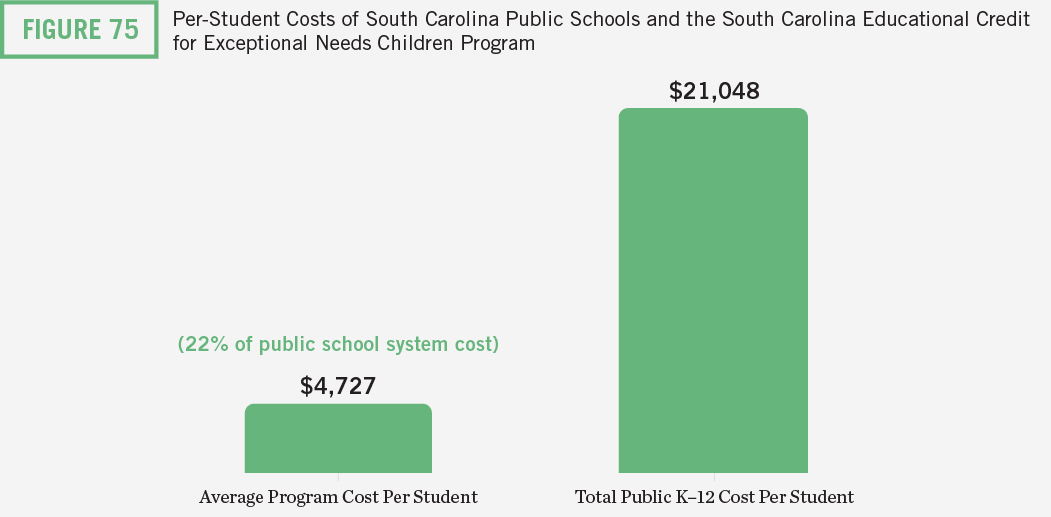

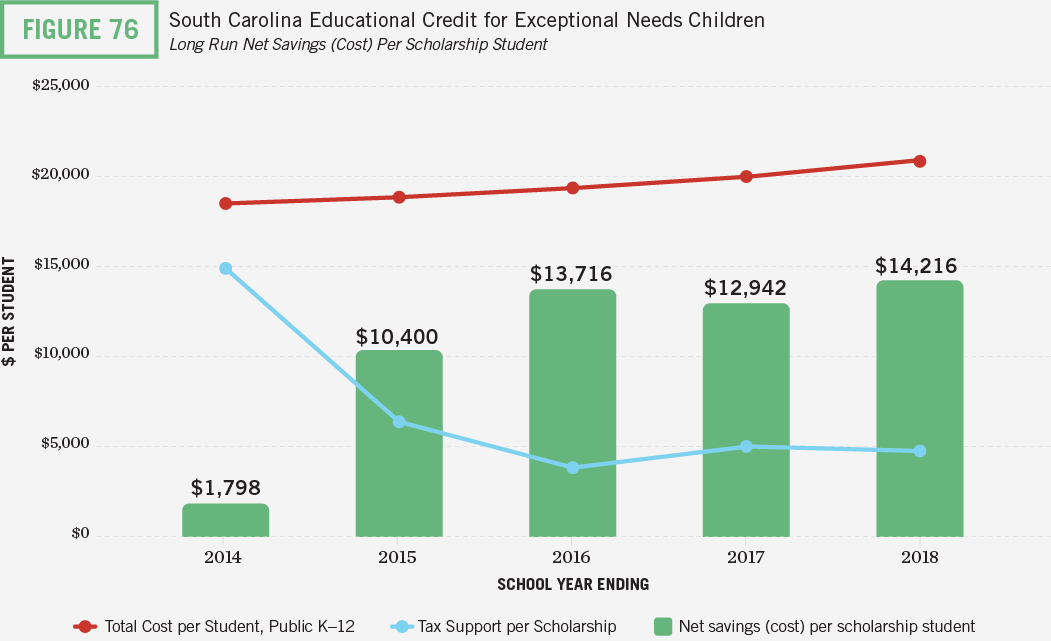

35. South Carolina’s Educational Credit for Exceptional Needs Children

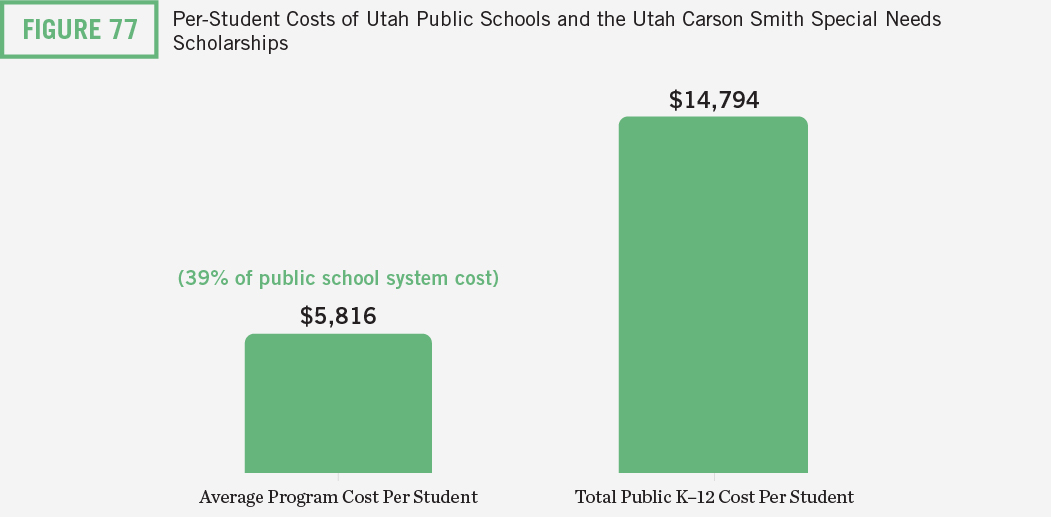

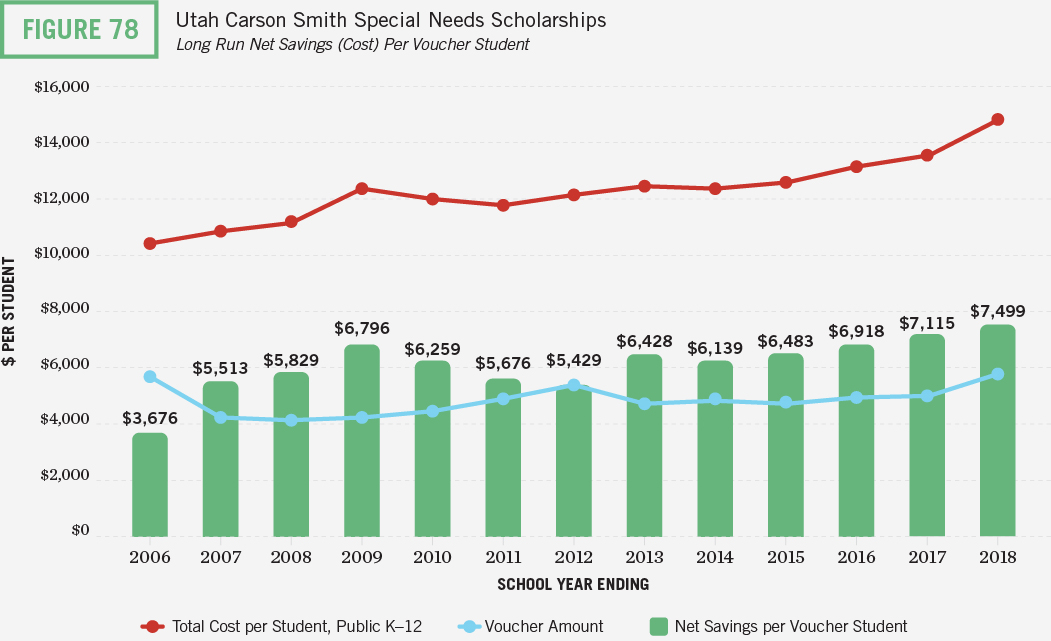

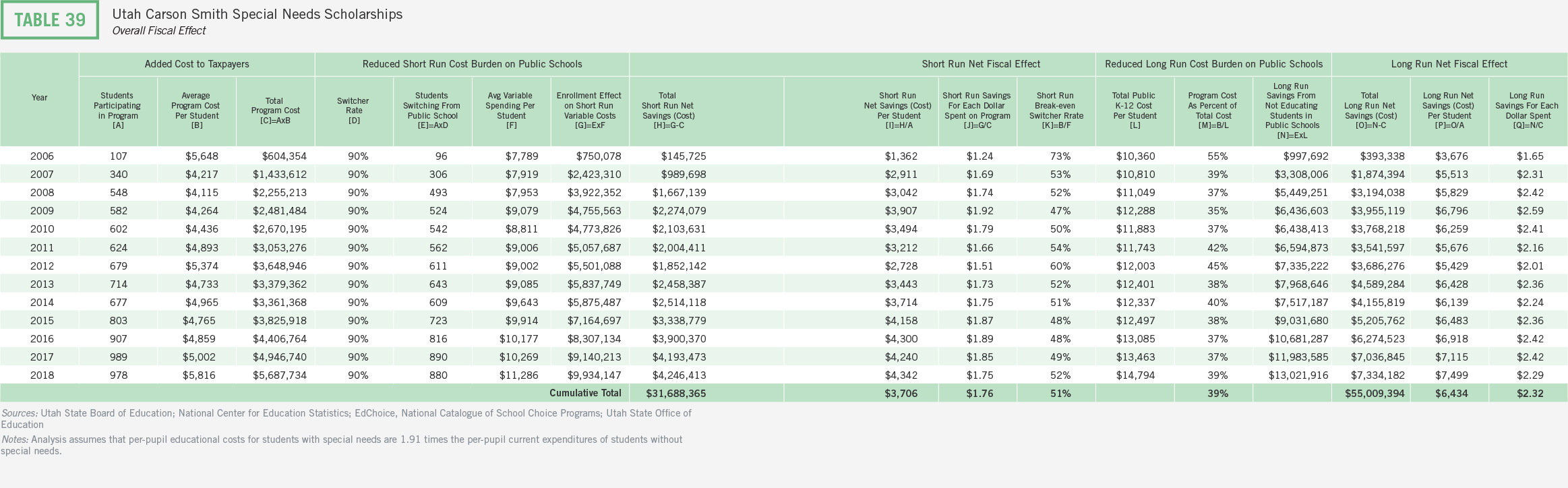

36. Utah’s Carson Smith Special Needs Scholarship

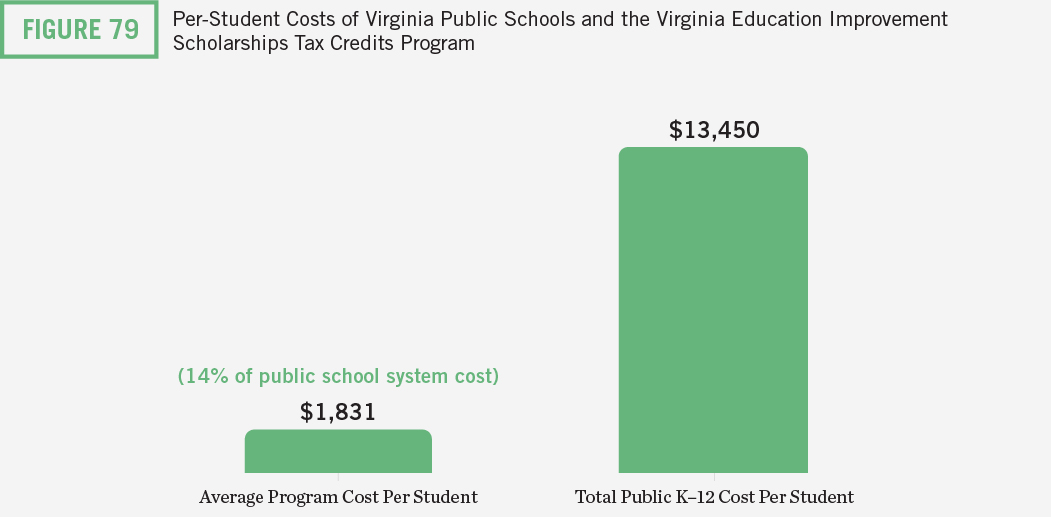

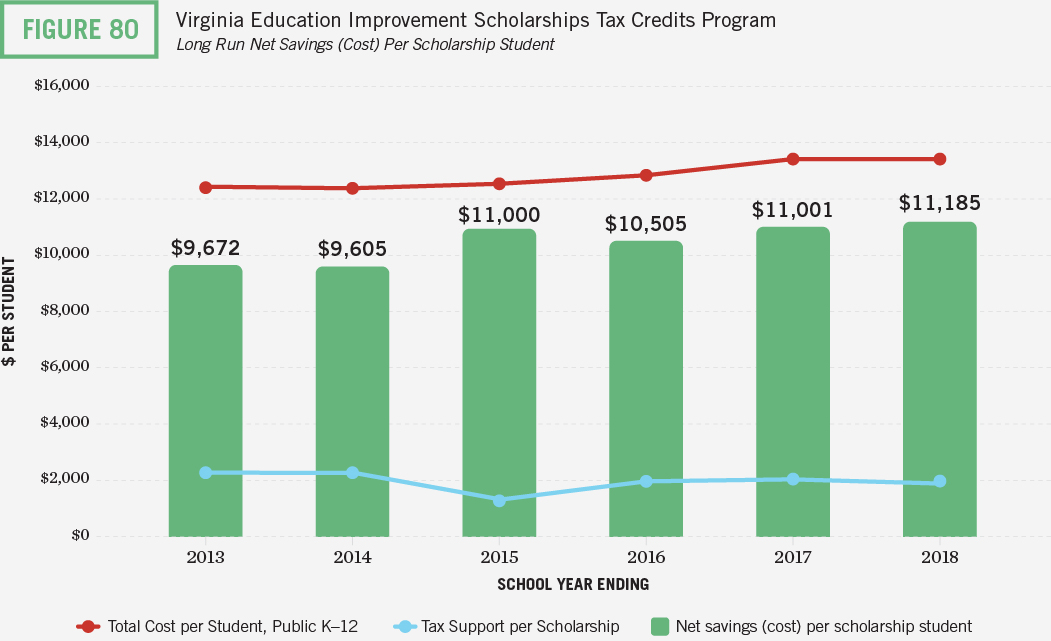

37. Virginia’s Education Improvement Scholarships Tax Credits Program

38. Wisconsin’s Milwaukee Parental Choice

39. Wisconsin’s Parental Choice Program (Statewide)

40. Wisconsin’s Parental Private School Choice Program (Racine)

Funding Context

A chief concern among educational choice opponents is that these programs will lead to a mass exodus of students from public schools, consequently harming public schools fiscally and leaving students who choose to stay in them worse off. Where choice programs currently operate, including states with the largest and oldest programs, it appears these concerns haven’t materialized.

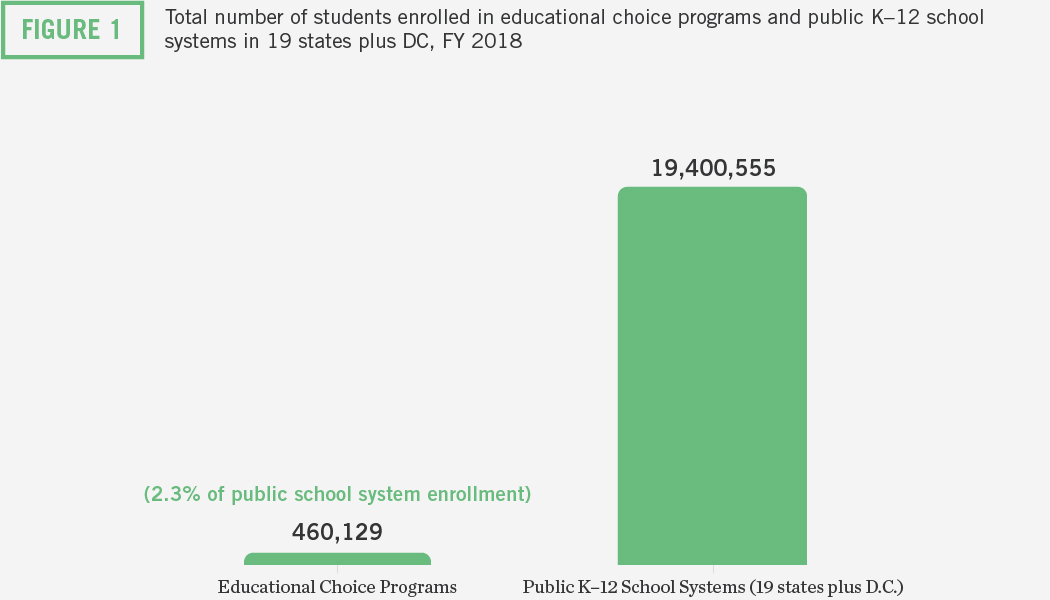

The cumulative number of education savings accounts, school vouchers, and tax-credit scholarships disbursed through FY 2018 for K–12 students to attend non-public school settings and access other educational services exceeded 3.7 million. In FY 2018, the number of students participating in educational choice programs comprised just 2.3 percent of all publicly funded K-12 students in states with choice programs (Figure 1).

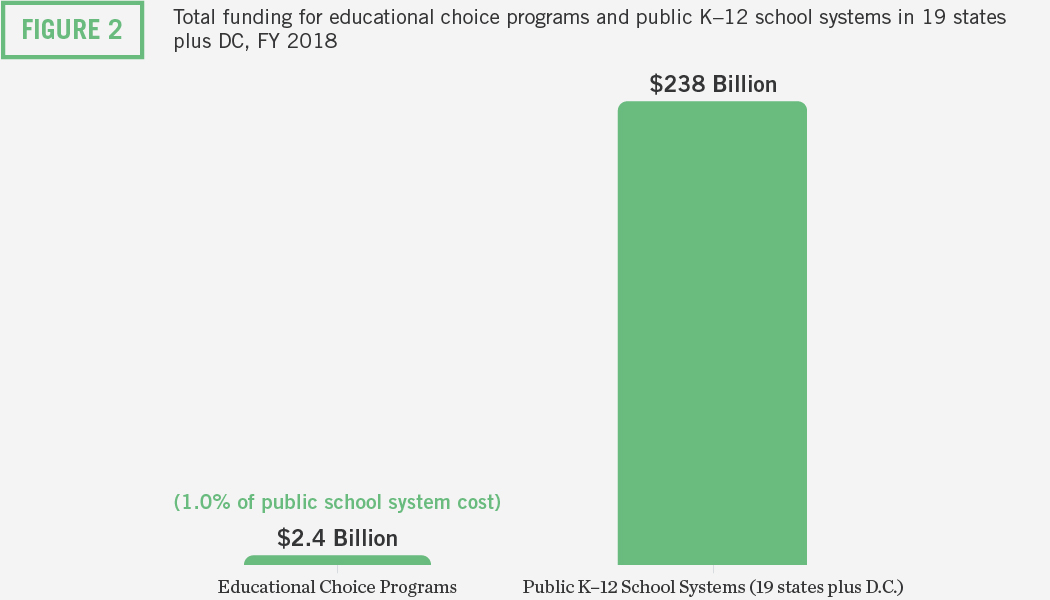

The total cost to taxpayers in FY 2018 to support the educational choice programs under study was 1 percent of taxpayer funding to support the public K–12 school systems in these 19 states plus D.C. (Figure 2). Educational choice programs in Florida received the largest share (3.3 percent) of public school costs while no other state’s share exceeded 3 percent. The share of public school costs is below 1 percent for 15 of the 20 states in the analysis.

Overall, choice programs enroll 2 percent of publicly funded students while receiving 1 percent of public funding for K-12 education. Thus, educational choice programs are funded at lower public expense than public K-12 school systems.

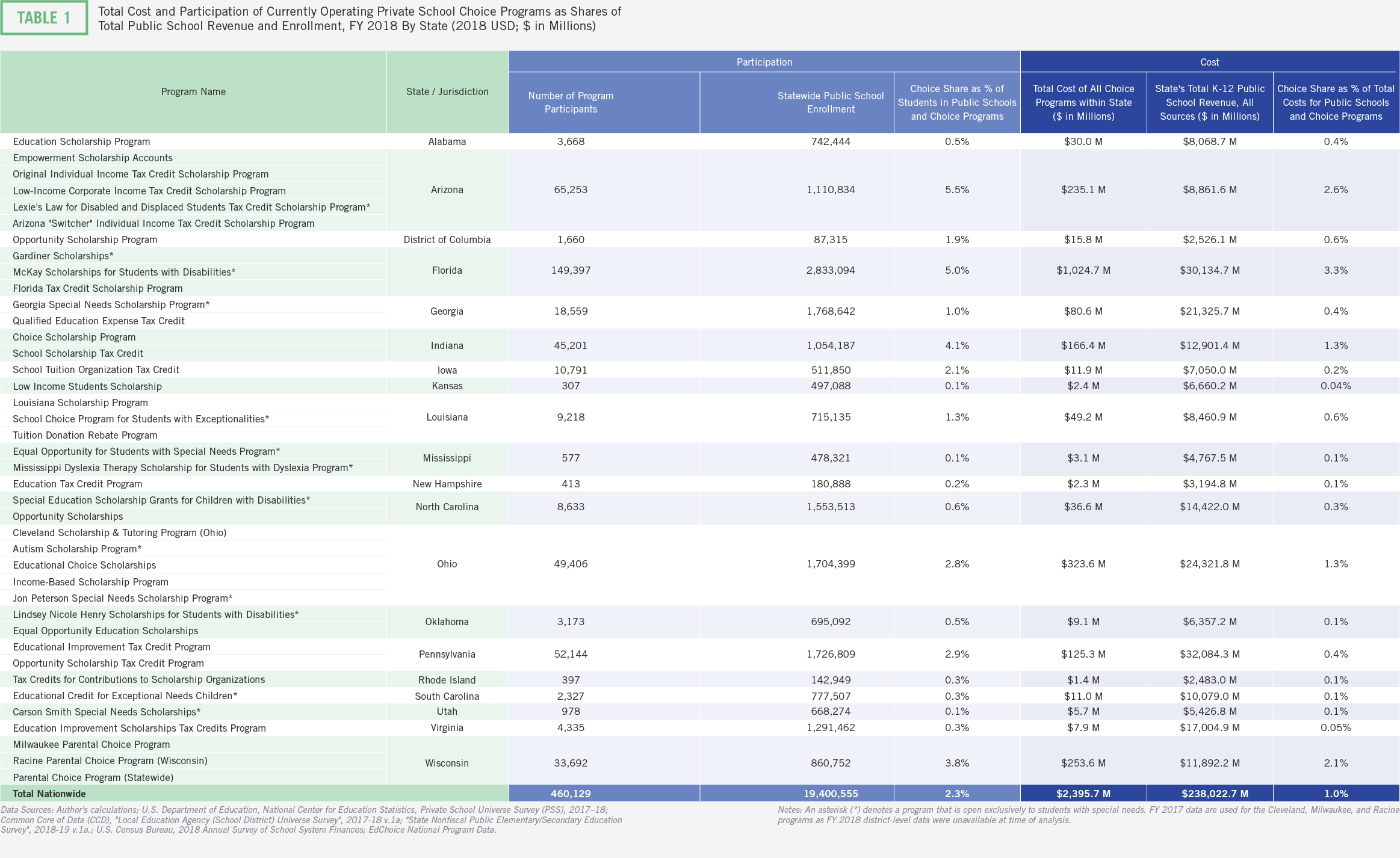

Table 1 shows participation and funding shares for each choice program. The left panel shows the total number of students participating in educational choice programs, each state’s total enrollment in public schools, and choice program participants as a percentage of enrollment in public schools plus choice programs for each state in FY 2018. The right panel shows the total cost to taxpayers to support each state’s educational choice programs; the amount of revenue from local, state, and federal sources that flows to each state’s public K-12 school system; and the choice share for each state in FY 2018 (expressed as a percentage of total costs for public schools plus choice programs).

Let’s look at states with some of the largest and oldest choice programs. Arizona’s five choice programs enrolled 5.5 percent of publicly funded students and received just 2.6 percent of public funding for K-12 in FY 2018. In Florida, choice programs enrolled 5 percent of publicly funded students while receiving 3.3 percent of public funds. In Indiana, the enrollment and funding shares were 4.1 percent and 1.3 percent respectively. In Ohio, choice programs enrolled 2.8 percent of publicly funded students while receiving 1.3 percent of public funding. And in Wisconsin, home of the oldest school voucher program in the country, choice programs enrolled 3.8 percent of publicly funded students and received 2.1 percent of the public funds.

The number of students participating in choice programs in half the states in the analysis (10) represent less than 1 percent of all students enrolled in public and private schools. Even in the states with some of the most vibrant choice ecosystems, the percent of students exercising choice is modest.

For all programs, the percentage of publicly funded students participating in choice programs exceeded the percentage of public funds directed to those programs. This suggests that choice programs generate fiscal benefits for taxpayers.

These basic facts provide important background for evaluating claims that educational choice programs harm students who remain in district schools. In light of this context, it may be difficult to see how expanding educational opportunities for families via educational choice programs might harm public school systems. To be sure, many studies have examined educational choice programs’ effects on students enrolling in nearby public schools. A handful of systematic reviews of competitive effects research and, more recently, one meta-analysis has been conducted by researchers.8 All of these reviews conclude that students who remain in district schools, after exposure to increased competition from choice programs, experience modest and positive gains in learning. Contrary to claims that students in district schools are harmed by increasing educational choice, the evidence suggests otherwise.

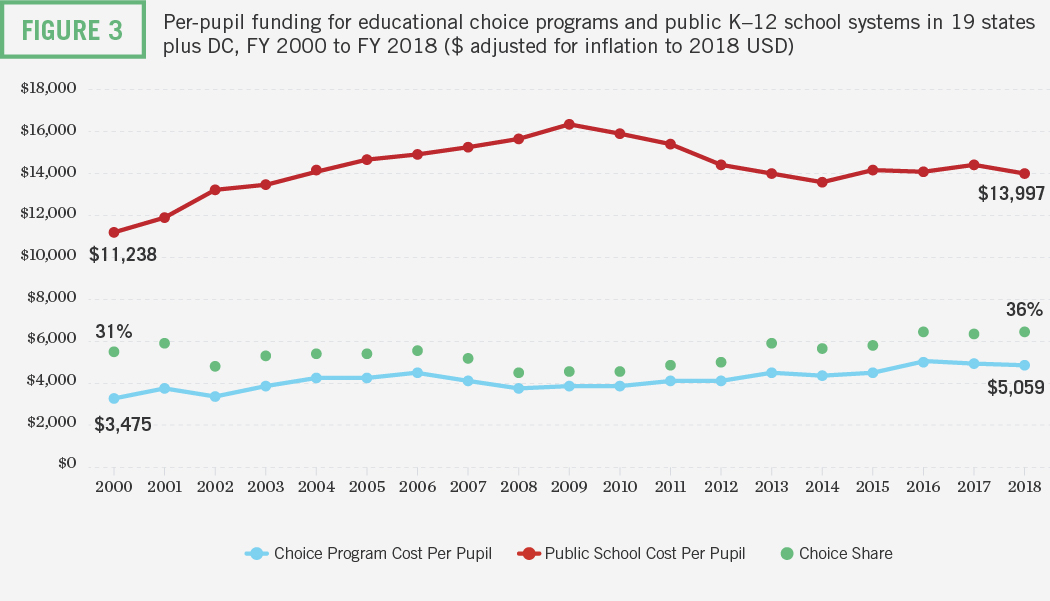

Student Funding Gaps

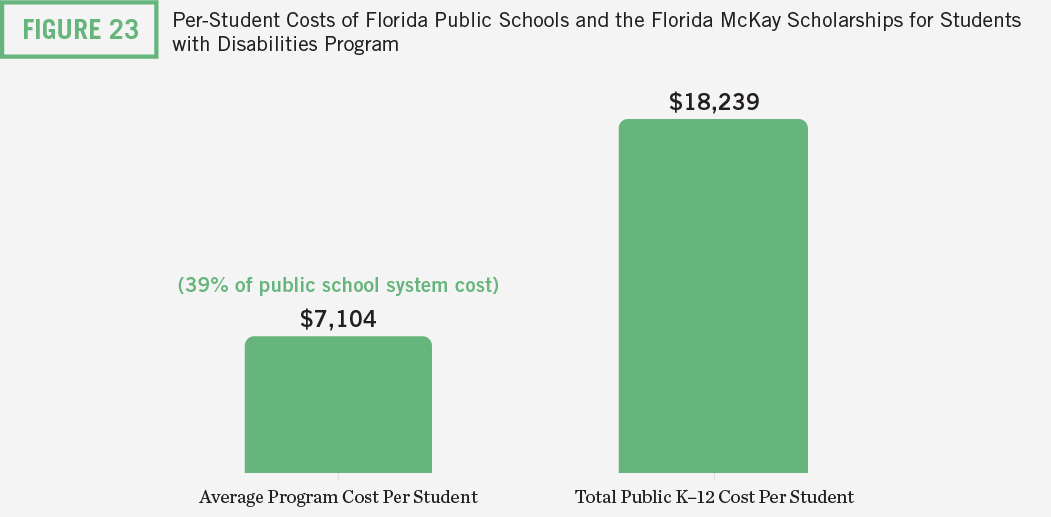

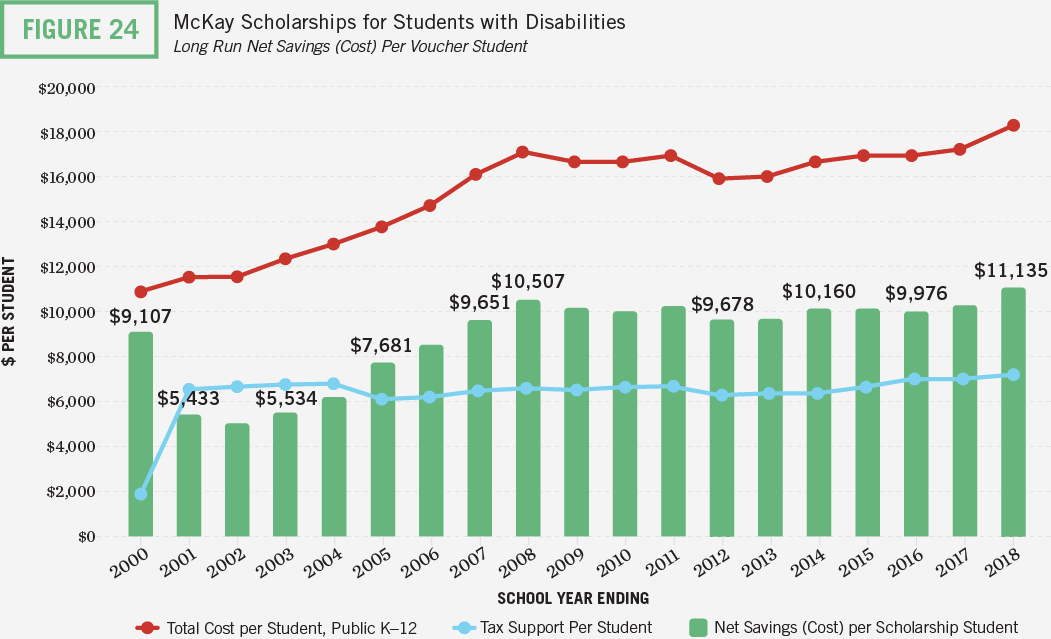

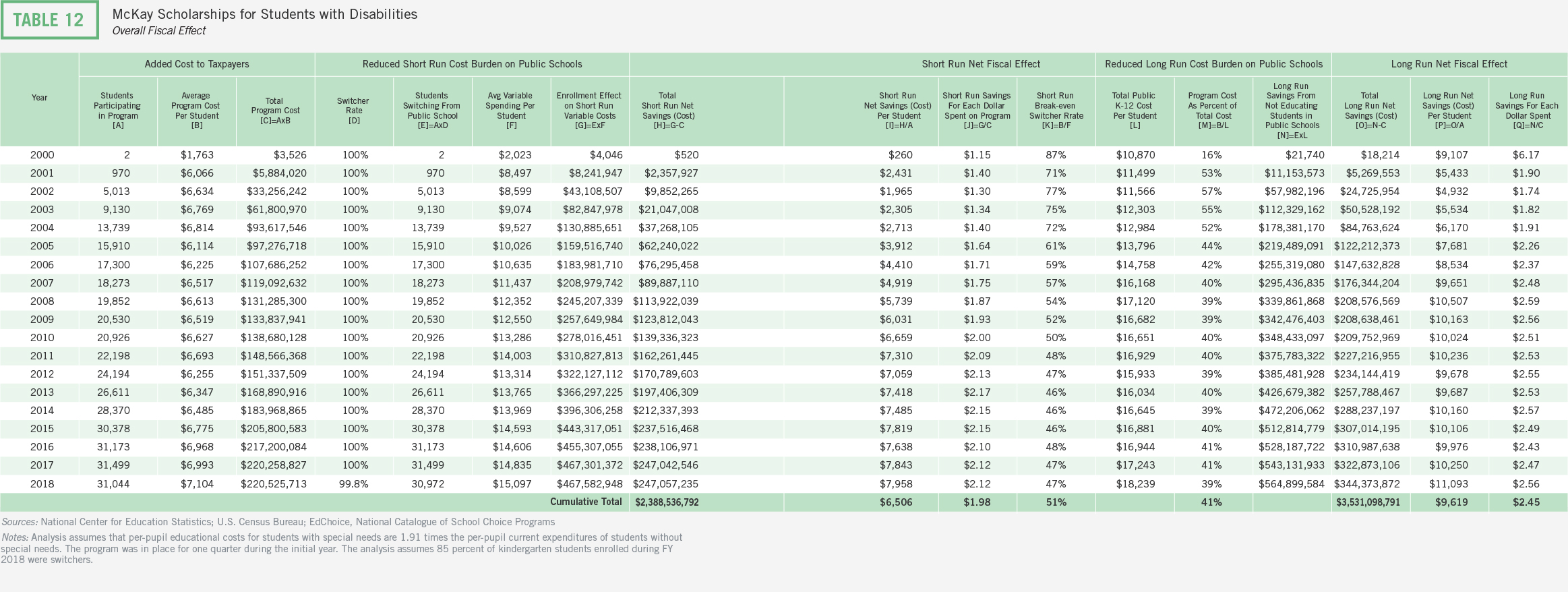

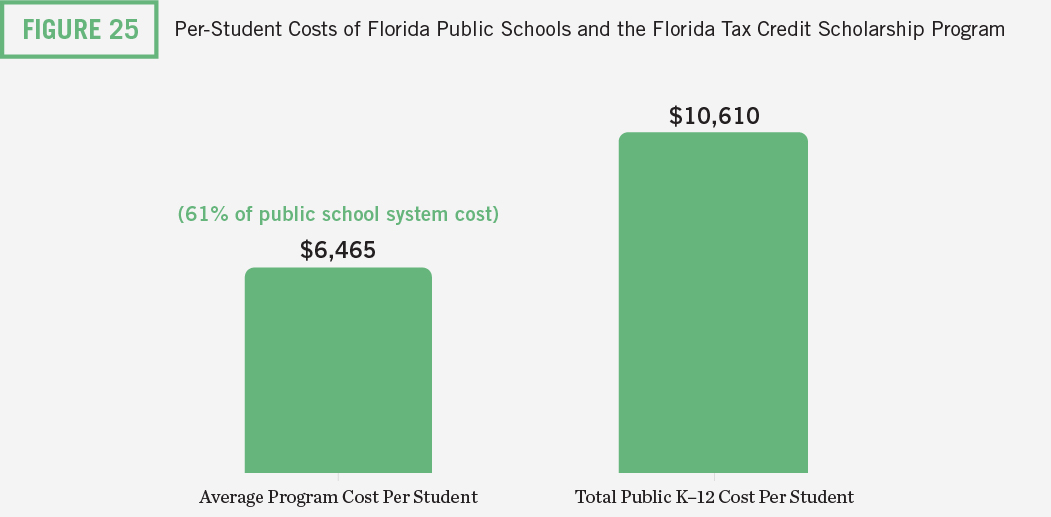

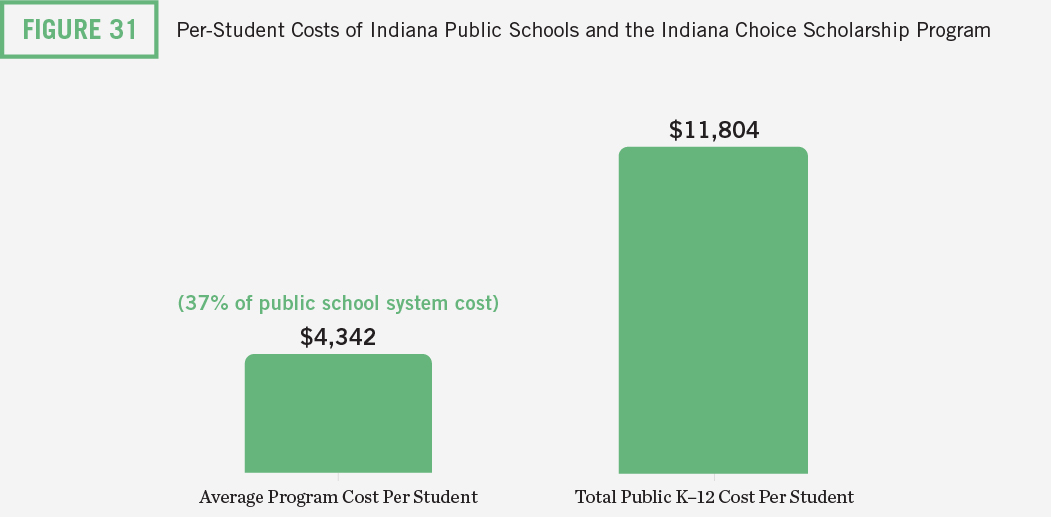

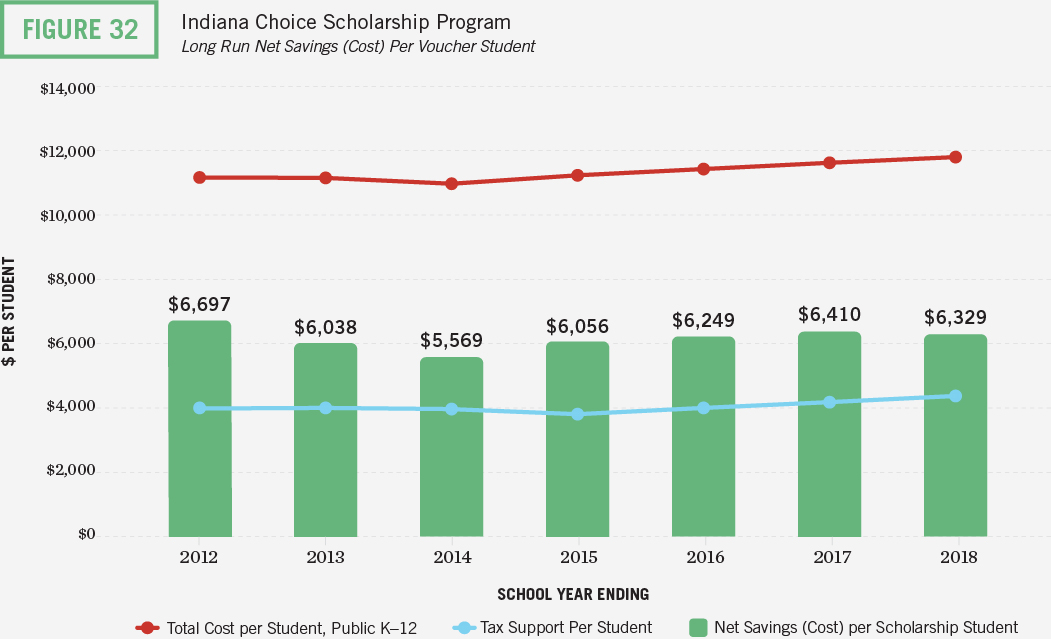

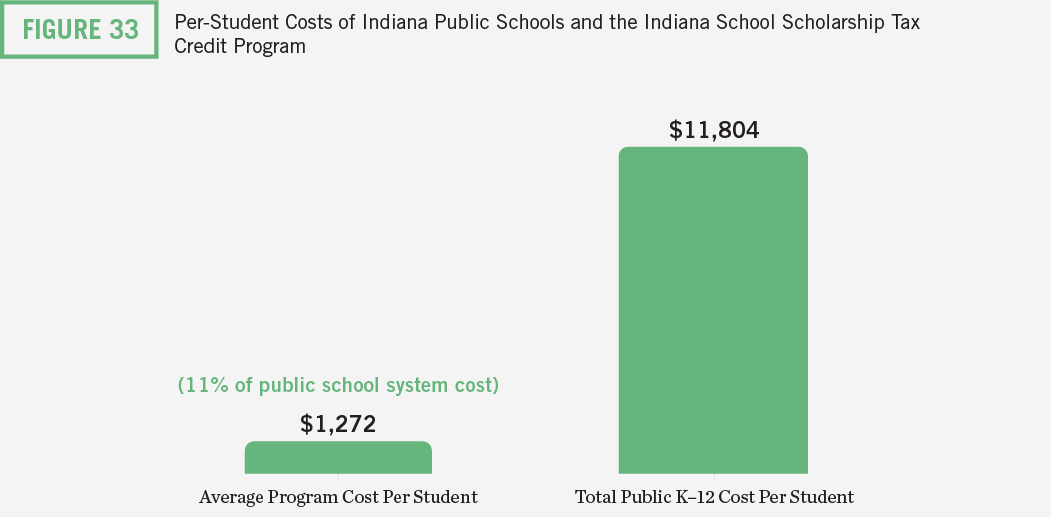

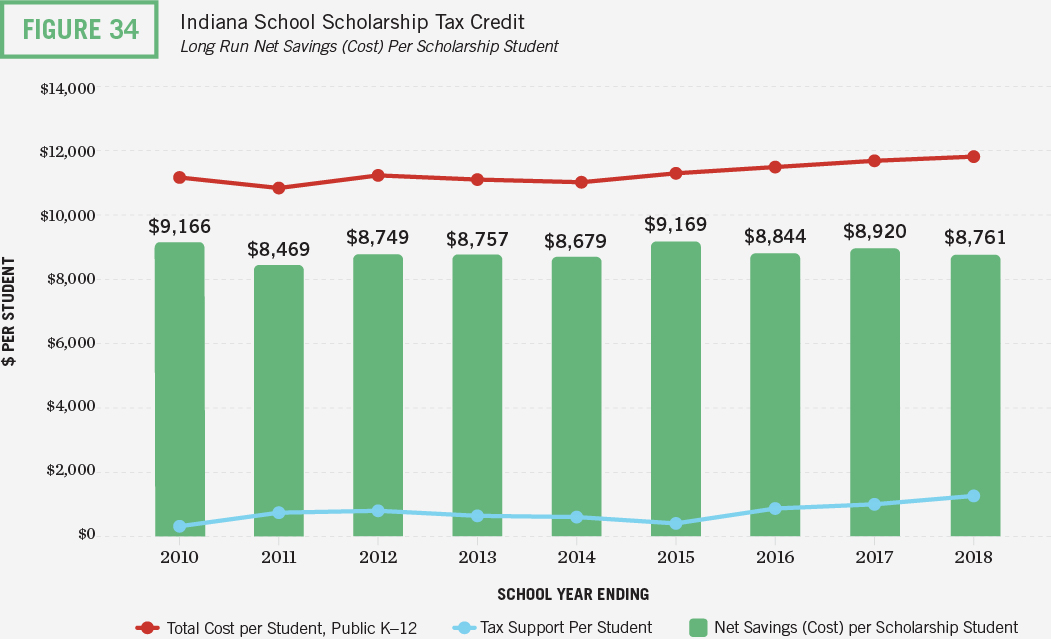

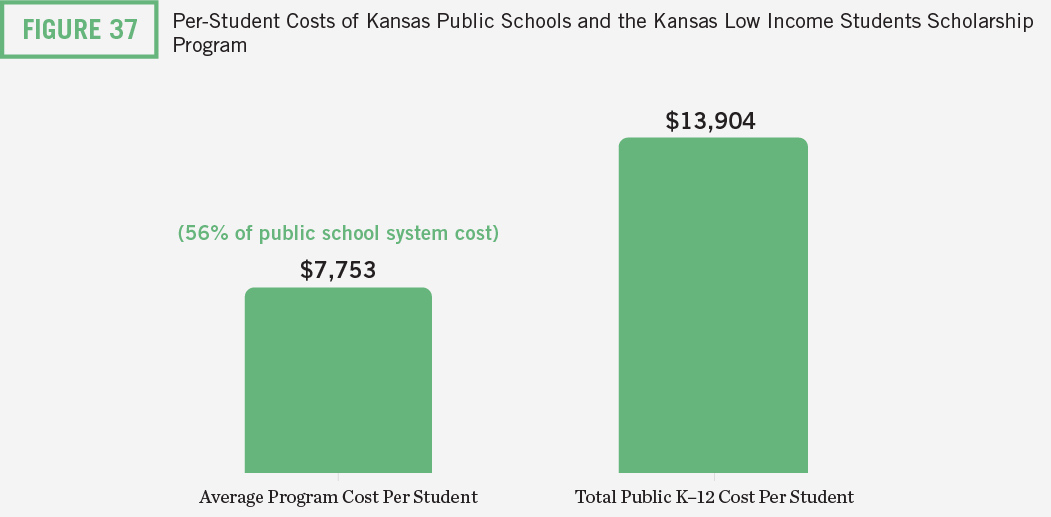

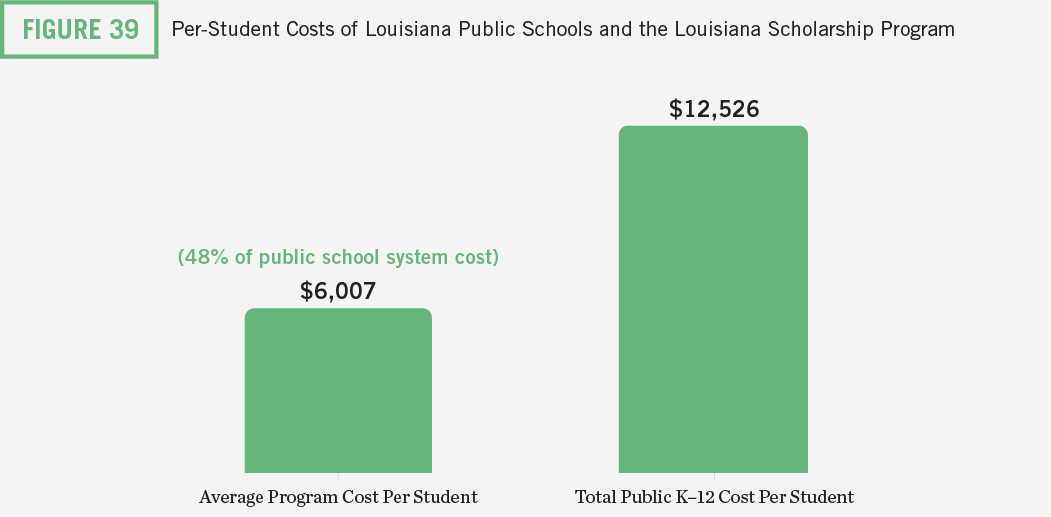

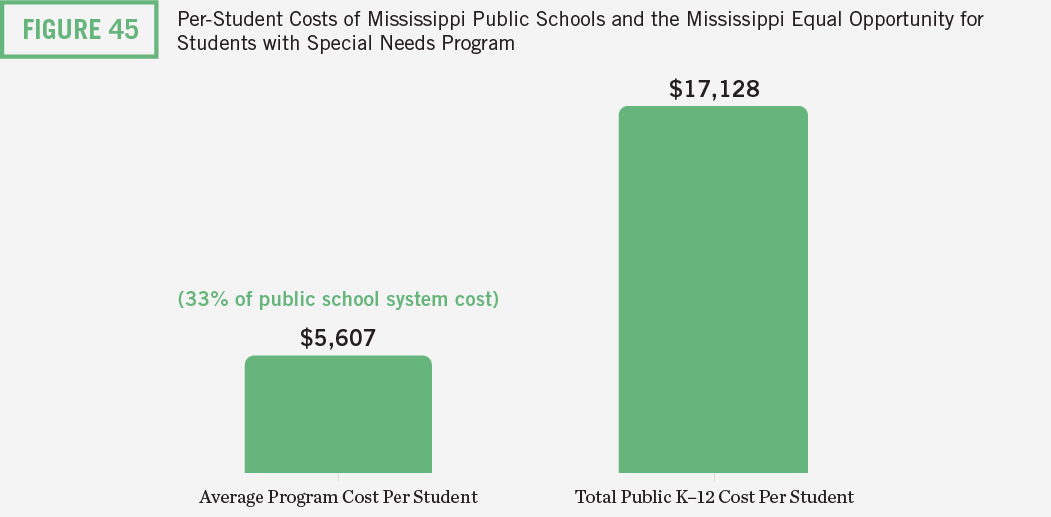

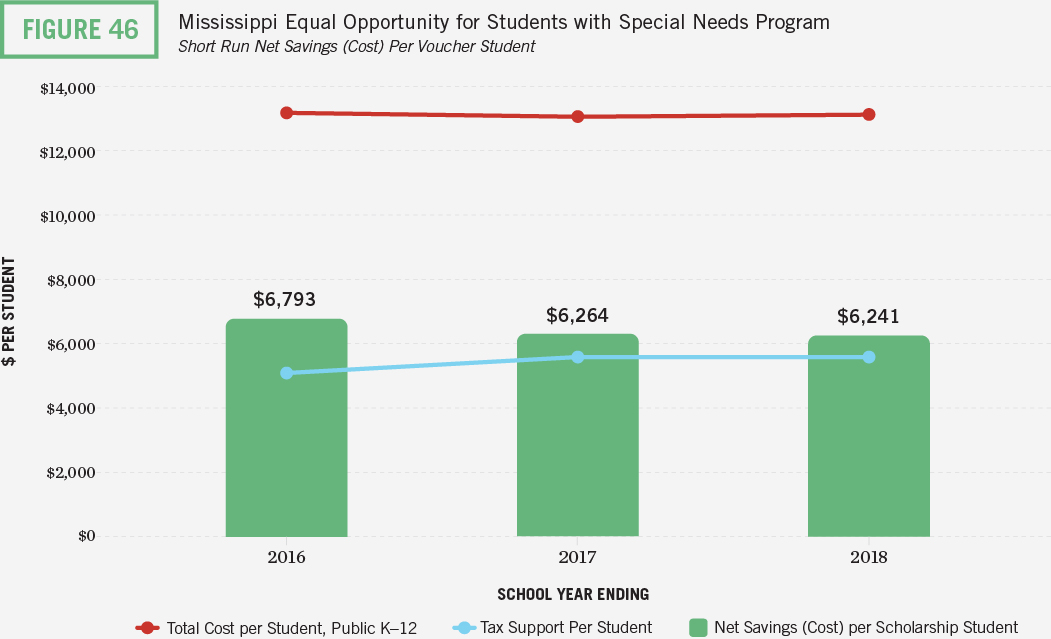

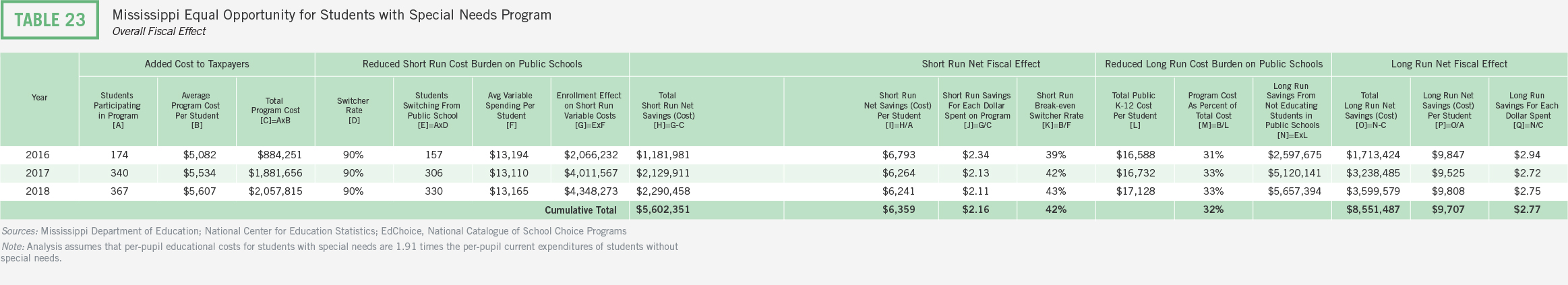

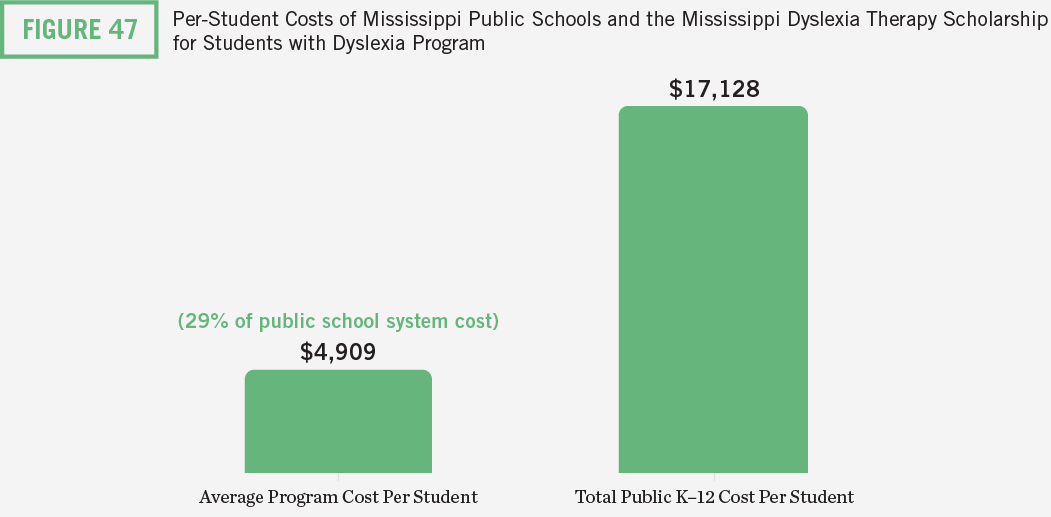

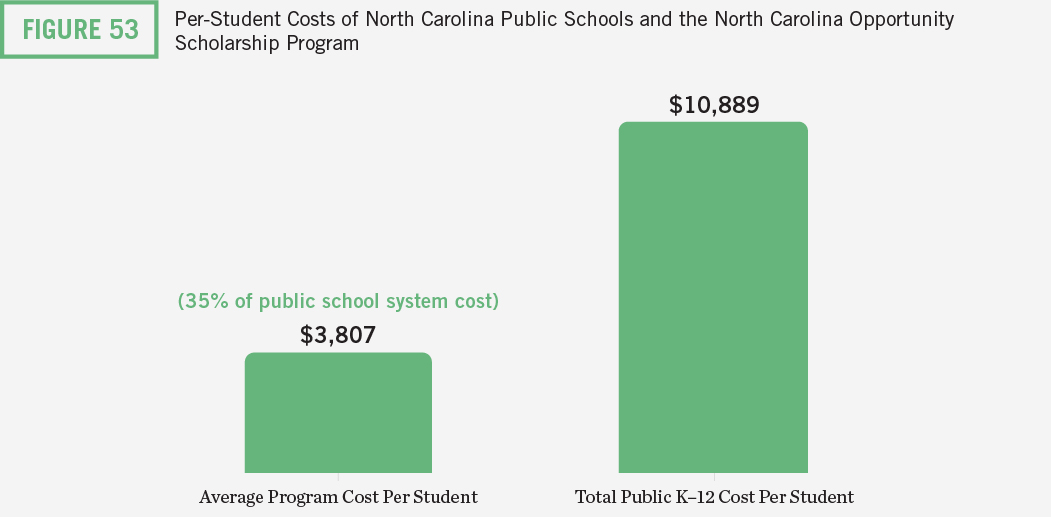

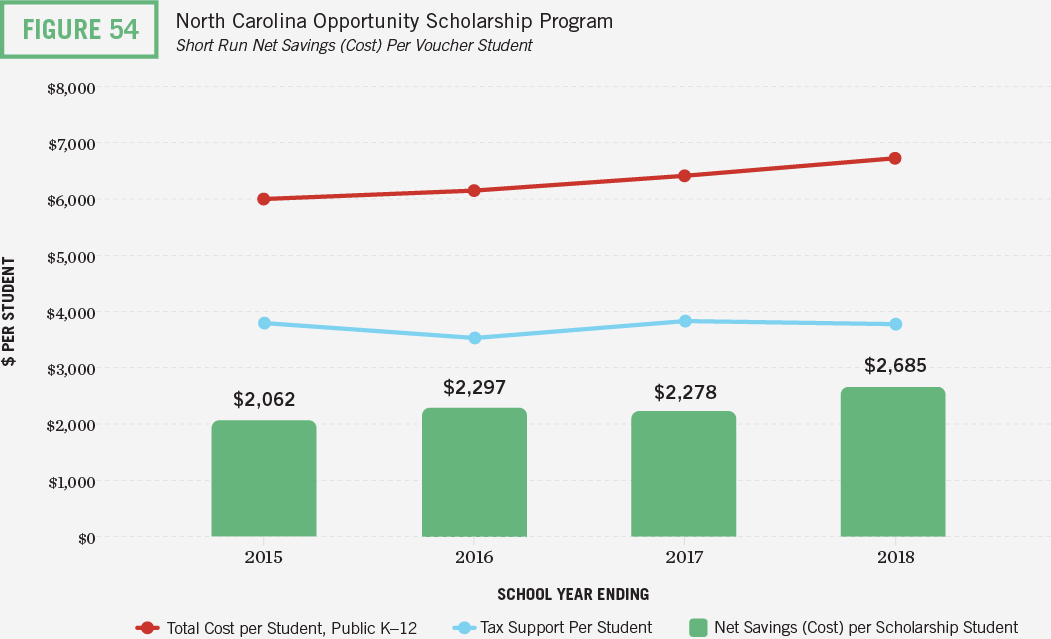

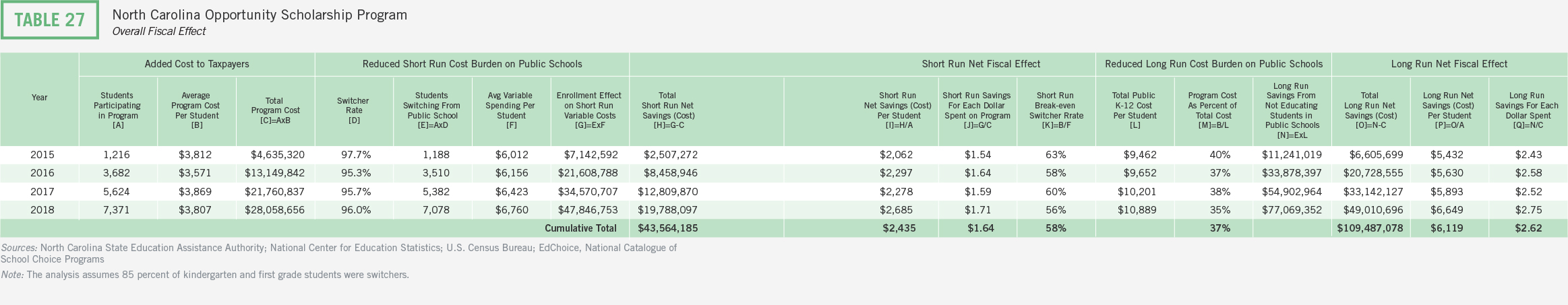

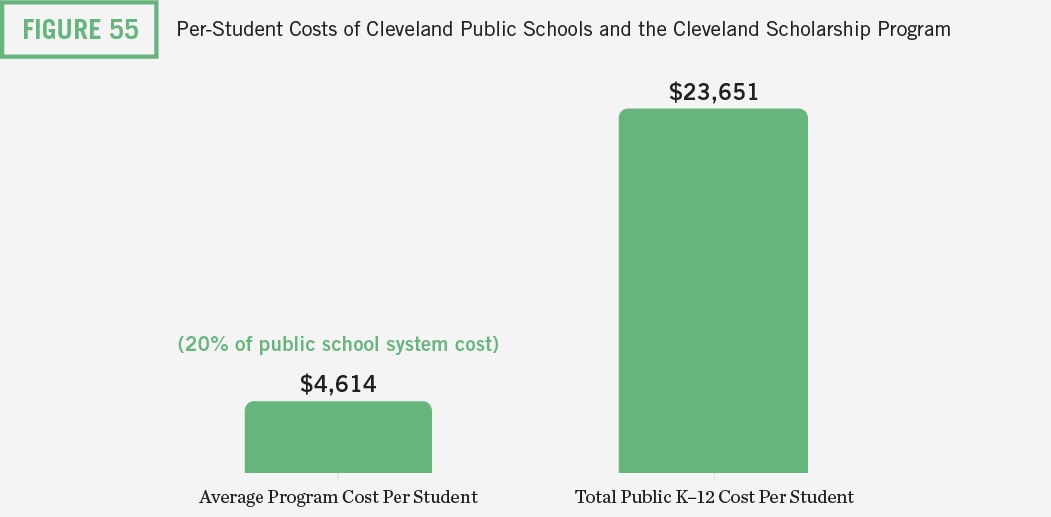

Figure 3 displays the per-pupil funding for choice programs and funding for public K–12 school systems between FY 2000 and FY 2018. The per-pupil cost of choice programs as a percentage of per-pupil public school funding slightly increased from 31 percent to 36 percent. In FY 2018, the average per-pupil funding for educational choice programs was 64 percent less than the average per-pupil funding for public schools ($5,000 vs. $14,000).9

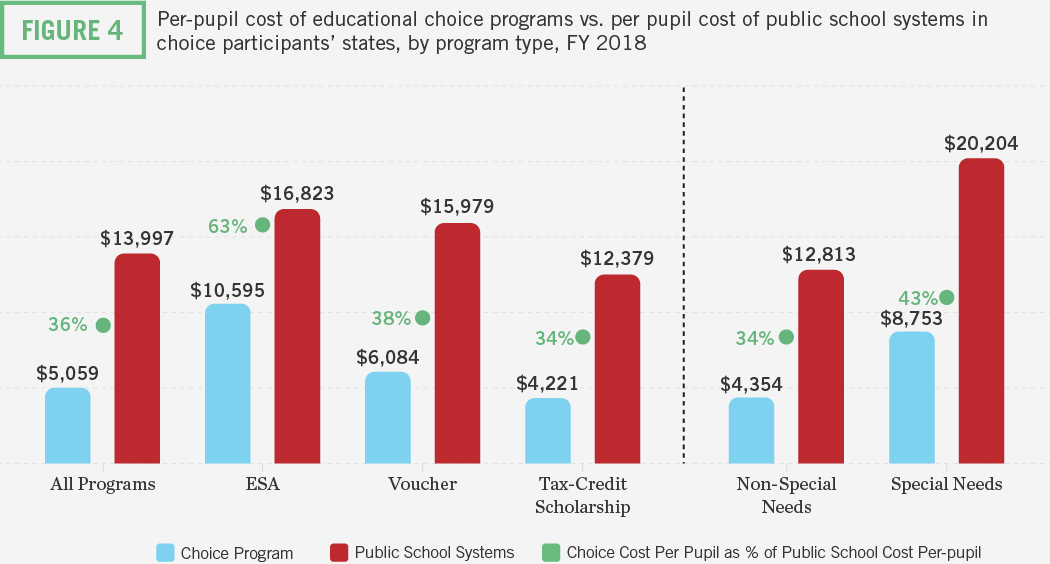

Figure 4 shows funding differences between choice programs and public school systems by program type. The three ESA programs in the study have smaller per-student funding gaps, where the average cost of ESAs per student is 63 percent of the estimated average cost per student of the ESA students enrolling in their respective public school systems. These costs are higher than the overall average cost of all choice programs and public K–12 because Florida and Mississippi ESA programs exclusively serve children with special needs, and more than half of students in Arizona’s ESA program have special needs.

Funding gaps for voucher and tax-credit scholarship programs are much greater, where average per-pupil funding for voucher and tax-credit scholarship programs are 62 and 66 percent less than average per-pupil funding for public schools respectively. Overall funding gaps for special needs programs and non-special needs programs are somewhat different, 43 percent and 34 percent respectively.

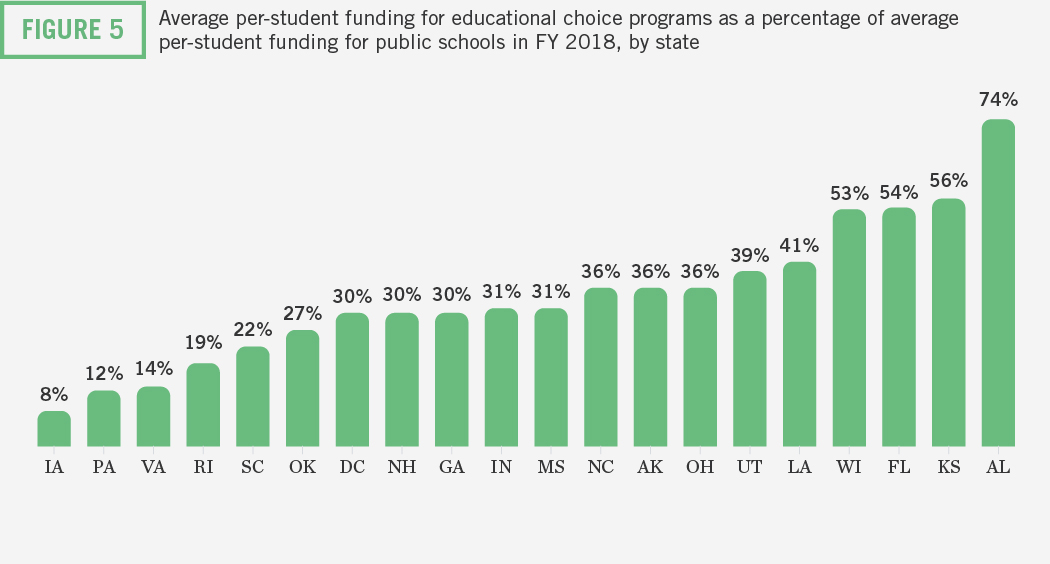

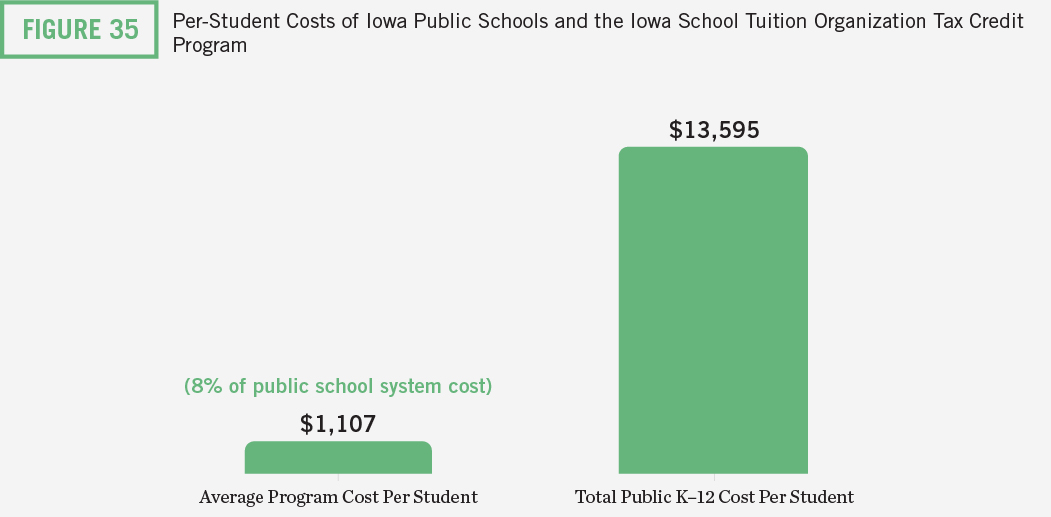

Figure 5 displays the percentage of per-student funding for public schools directed to educational choice programs for each state. Average funding per-student as a percent of per-student funding for public school systems ranges from 8 percent (Iowa’s tax-credit scholarship program) to 74 percent (Alabama’s tax-credit scholarship program).

Students in choice programs located in about half of states in the analysis (11 of 20 states) received less than one-third of revenue they would receive in public schools. For four-fifths of the states, choice programs received less than half the per-student funding they would have generated for public schools. These states enrolled more than 60 percent of students participating in the 40 programs considered during FY 2018.

These gaps indicate significant fiscal benefits for taxpayers and school districts when students are redirected from the public school system via choice programs. Moreover, funding systems for public schools are not completely based on student enrollment. Therefore, districts tend to benefit fiscally because they often keep a significant portion of the per-pupil funding for students who leave. For example, districts in some states such as Georgia and Indiana keep all local revenue—only state revenue is tied directly to enrollment.

Most states also have either declining enrollment provisions or “hold harmless” funding provisions embedded in their funding systems. These provisions guarantee districts all or most of the basic education funding they received for the prior year or some other year in the past, even if enrollment declines. Declining enrollment provisions, to a lesser extent than “hold harmless,” mitigate the fiscal impact of declining enrollment.10

Funding policies tend to produce a happy fiscal byproduct for district schools where public schools end up with more resources on a per-student basis, all else equal. Such arrangements, however, raise questions about funding equity and how governments fund different groups of students. A single student can generate significantly different amounts of revenue for schools in different settings or districts.

Large funding gaps between the public cost of educational choice programs and public school systems indicate substantial fiscal benefits that accrue to taxpayers when students switch from public to private schools as a result of choice programs.

Educational Costs

Concerns about the fiscal impacts of educational choice programs are usually focused on short-run costs facing public school districts. In the short term, some costs vary completely or partially with enrollment while in the long run all costs are variable. Long run may be used as a time-based concept. When a school gains or loses students, its options are somewhat limited in the immediate term. For example, because school budgets are usually set on an annual basis, they may be limited in how they can respond to enrollment changes mid-year. Over time, however, public schools and districts will have more options for them to adapt, such as finding more cost-effective ways to deliver a curriculum or program.

Even over a long period of time, however, options to reduce costs may be limited or unrealistic. In most cases, it doesn’t make sense to hire an additional full-time teacher when one additional student enrolls. Therefore, long run may also relate to the size of changes in student enrollment. The larger an enrollment change, the more opportunities districts will have to adjust costs. For example, a school may open, close, or merge classrooms, or a district may build new buildings or consolidate schools.

One line often used to express concern about the fiscal effects of choice programs is that schools “need to keep the lights on.” That is, because of high fixed costs, educational choice programs will render districts unable to cover their fixed costs without harm to students. If this were true, then it follows that there would be little to no added costs when enrollment increases. Of course, this is not the case. To be sure, some public school officials that levy these arguments against choice programs will also request more funding because they anticipate enrollment growth—thus, they either believe that they have high fixed costs or high variable costs. Both cannot be true, however.

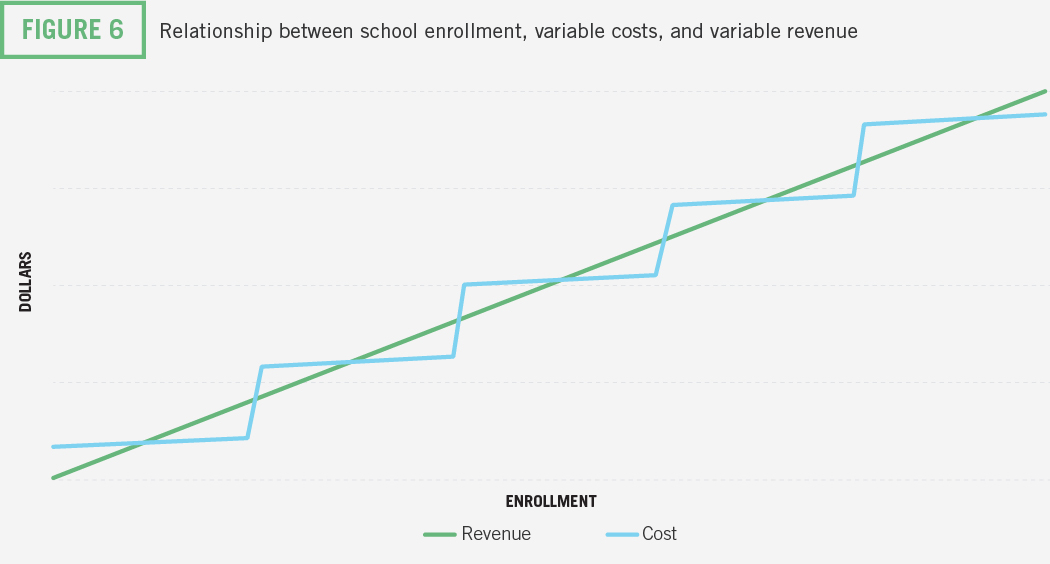

In reality, both revenues and costs change with enrollment, though not in perfect unison. Figure 6 illustrates this reality. Over a broad range of enrollment, costs and revenue correspond to enrollment changes. Over a small range of enrollment change, a school may incur a reduction or increase in revenue while most of its costs remain flat. This corresponds to the horizontal portion of each step. If a school gains or loses a few students, it wouldn’t necessarily be in the best interest of the school to add or remove a teacher based on small fluctuations in student enrollment. Staffing is not easily changed on a per-student basis.

It’s also notable that the change in revenue associated with small changes in enrollment represents a relatively small portion of a large budget. Enrollment fluctuations are a reality that districts have long dealt with, and changes in demand for services is not unique to schools. All kinds of enterprises face this reality (e.g., pre-kindergarten, colleges and universities, hospitals, law firms, and grocery stores).

Financial management is a standard part of the educational landscape that officials handle on a routine basis. Certainly, school officials face real challenges when revenue declines, and those challenges shouldn’t be dismissed. The point here is that the challenges from a decrease in revenue are not a problem uniquely tied to educational choice. It is a natural part of the education landscape that school officials routinely face: families move in and out of districts and schools for all kinds of reasons. And it is not a “choice problem.” The fiscal effect on school districts from students leaving choice programs is the same as the fiscal effects from students who leave for other reasons. If one’s opposition to a choice program stems from effects on finances, then it follows that he/she would also oppose families moving among districts and support policies that prohibit such movement.

This report endeavors to provide policymakers with information about the overall fiscal effects of educational choice programs. To be clear, it does not describe what financial decisions were made by school officials when students left to participate in educational choice programs. The analysis describes what costs can be adjusted in the short run, rather than what costs were adjusted or will be adjusted.11

Methods

Educational choice programs create a direct cost for taxpayers because taxpayers pay for ESAs and vouchers, and tax-credit disbursements reduce the amount of tax revenue received. There also is a direct fiscal benefit from students who choose to not enroll in public schools because of the receipt of a scholarship.

The net fiscal effect of a choice program is the difference between savings from switchers and the program’s costs:

Net Fiscal Effect = [Cost Reduction from Switchers] – [Cost of the Choice Program]

Switchers are students who would enroll in a public school without financial assistance from an educational choice program. Measuring the fiscal effects of educational choice programs represents a complicated exercise. Not only does school funding come from different sources (federal, state, and local governments), but complex school funding formulas determine the allocation of these revenues.

Isolating the fiscal effects of a choice program to a single group of taxpayers would require applying each individual state’s school funding formula. Doing so for just one program would necessitate a significant undertaking. For this reason, this report reports lower bound (short-run) and upper bound (long-run) estimates for the fiscal effects of educational choice programs that accrue to state and local taxpayers combined. This approach is appropriate for a fiscal analysis that is national in scope—and because taxpayers in each state pay both state and local taxes. The analysis that follows provides a fiscal picture for each program that is useful for examining the extent to which these programs generate net fiscal benefits or net costs overall.

Short-run net fiscal effect (NFEs)

The analysis uses estimates of short-run variable costs to evaluate the short-term net fiscal effect (NFES) of educational choice programs. The net fiscal effect by a given program on the state budget is captured by the following equation:

NFES = [RS x E x s] – [C x E] (1)

In equation (1), RS is the average revenue per pupil retained by the state for a student who leaves a public school system via the choice program; E is the total number of students who participate in the choice program; s is the switcher rate (the percent of program participants who are switchers); and C is the average cost per student to provide ESAs, vouchers, or tax credits. The last term (C x E) is the total cost of a choice program. For tax-credit scholarship programs, the analysis uses tax-credit disbursements instead of the amount of scholarships awarded. These amounts can differ if the tax-credit rate is not 100 percent or if a program allows SGOs to use a portion of donations for administrative costs. The term (RS x E x s) signifies savings from student switchers and represents relief from the cost to state taxpayers to support the education of these students in the public school system.

The net fiscal impact on local taxpayers and public schools (NFEL) is:

NFEL = [AVC x E x s] – [RS x E x s] (2)

AVC represents estimated short-run average variable costs per student in public schools. Note that RS is a cost to public school districts and local taxpayers—it represents reduced state revenue from students who leave a public school. RS is determined by a state’s school funding formula and can vary significantly by school district. This term appears in equations (1) and (2) above. When a student leaves a public school, that student concurrently creates savings for the state and a reduction in state revenue for their school district.12

Adding (1) and (2) above yields the combined net fiscal effect on state and local taxpayers (NFE) in the short run:

NFE = NFES + NFEL = [AVC x E x s] – [C x E] (3)

The term [RS x E x s] from equations (1) and (2) drops out in equation (3). It represents savings for the state and a revenue reduction for public schools. Because non-switchers (i.e., students who previously enrolled in private schools absent financial assistance) represent an additional cost to taxpayers, a greater migration of students from public schools into a choice program implies greater savings from the state’s point of view and a greater reduction in state revenue that public schools receive, all else equal.13

Long-run net fiscal effect (NFE*)

A fundamental economic principle maintains that in the long run, all costs are variable. The long-run fiscal effect (NFE*) of choice programs is estimated by comparing the total per-student cost of educating students in the public school system (denoted TC) with the public cost of supporting those students in educational choice programs:

NFE* = [TC x E x s] –– [C x E]

Equation (4) says that NFE* is the difference between the total cost to educate students in the choice program who would have enrolled in the public school system without financial assistance and the total cost of the choice program. This estimate represents an upper bound and estimates from equation (3) represent a lower bound. Several years after the creation of a new school choice program, once enrollment patterns steady and local public school district leaders have time to adjust, savings will approach these long-run estimates.14

Estimating Short-Run Variable Costs

Our approach for estimating short-run variable costs employs school finance data from the National Center for Education Statistics and uses the same accounting methods from Lueken (2018).15 Variable cost estimates comprise three categorical expenditures: Instruction, Instructional Support Services, and Student Support Services. The analysis assumes all other categorical expenditures as fixed including capital, maintenance, debt service, administration, transportation, food service, enterprise operations, and numerous other categorical expenditures. Some of these excluded categories, such as transportation and food service, are likely variable or partially variable in the short run.

This approach is more cautious than methods used by some economists and will generate smaller savings estimates.16 In addition, the analysis below applies an adjustment to variable cost estimates for students with special needs, discussed in more detail below.

Estimating Switcher Rates

A student who switches from a public school, only because they received a scholarship, will generate savings overall if the short-run variable cost exceeds the program cost for that student (AVC > C). Non-switchers are students who would have enrolled in a nonpublic educational setting anyway even without a choice program in place. They represent a fiscal cost equal to the program cost without any savings. Two main factors determine the estimates of the fiscal effects of educational choice programs:

- The number of students who would have attended public schools without the financial assistance from the educational choice program (switchers), and

- The education costs directly associated with the switching student that will no longer be spent by the school district (variable costs).

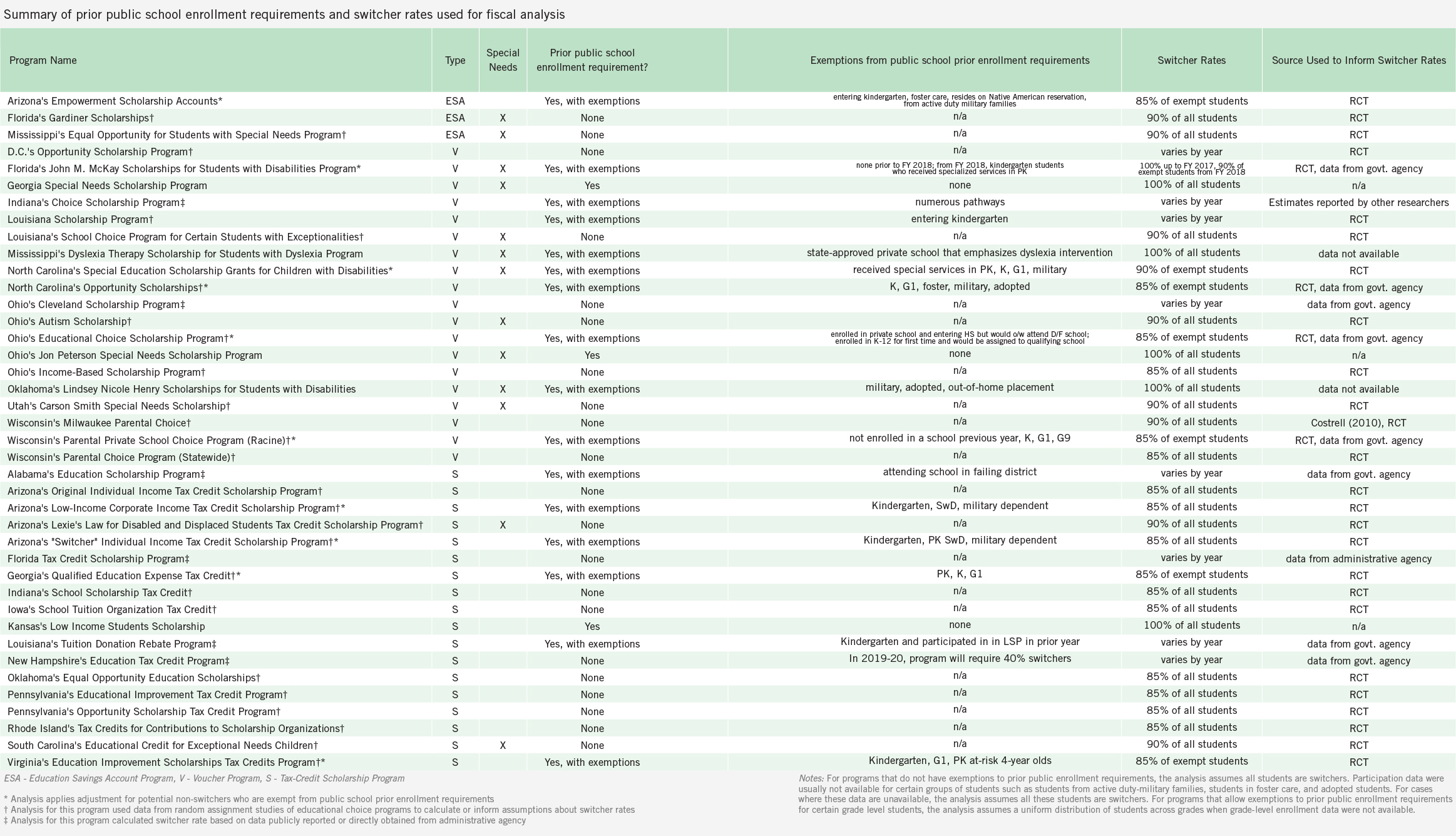

I contacted state government agencies and non-profit organizations involved in the administration of these programs to request information about the types of school settings students were enrolled prior to participating in the program. Many programs require eligible students to have been enrolled in public schools during the previous year, though these requirements vary in the required enrollment duration and groups of students who are exempt from these rules. Examples of students exempt from public school prior-enrollment requirements may include kindergarten, students in foster care, and students from families where parents are active-duty military.

The appendix table includes information about public school prior-enrollment requirements and assumptions for switcher rates used in the analysis. For programs with public school prior-enrollment requirements for eligibility without any exceptions, the analysis assumes all students participating in the program are switchers. For programs with exceptions to these rules, the analysis assumes 85 percent to 90 percent of exempt students are switchers, where the 85 percent adjustment is applied to non-special needs programs and 90 percent is used for special needs programs.17

If a program has no prior enrollment requirements or exemptions to these requirements and prior enrollment data were not available, the analysis cautiously assumes an 85 percent switcher rate. This assumption is based on a survey of random assignment studies which analyzed information from random assignment studies of private school voucher programs to infer switcher rates.18

Break-even Switcher Rate

The overall break-even switcher rate (BER) gives the percentage of students participating in an educational choice program who must be switchers for the program to be fiscally neutral. It is the rate that balances the program’s costs with savings.19 By setting NFE equal to zero in (3), the break-even switcher rate is simply the ratio of the average cost of the program to the average variable cost per student:

BER = C / AVC

A program generates net savings in the short run if the switcher rate is greater than BER. If the switcher rate is less than BER, then the program results in net costs. Here’s an example. If the average voucher amount is $10,000 and the average variable cost to educate a student in public schools is $15,000, the break-even switcher rate is 67 percent (=$10,000/$15,000). Thus, as long as more than two-thirds of students using the program are switchers, then the program saves taxpayers money.

Students with Special Needs

Thirteen educational choice programs included in the analysis are open exclusively to students with special needs. For the programs that do not have prior public school enrollment requirements, the present analysis assumes that 90 percent of students participating in educational choice programs for students with special needs are switchers. Given the disadvantaged background and higher education costs of students with special needs, it’s likely that a high proportion of are switchers. The 90 percent assumed switcher rate is lower than that used in previous analyses, where all students participating in special needs choice programs were assumed switchers.20 This assumed rate lies within the range of switcher rates observed in lottery-based studies of programs serving non-special needs student populations, this assumption is likely cautious.

Relative to the general student body, the costs for serving students with special needs can vary dramatically depending on the severity of their disabilities. This creates a unique challenge to estimating fiscal effects for programs that serve special needs students.21

To estimate average total per-pupil costs for students with special needs, the analysis applies a factor of 1.91 to the per-pupil current expenditures for all students in the public K–12 school system.22 The analysis assumes that educational costs for children with autism or multiple disabilities is 3.00 times the state’s average per-pupil current expenditures.23

Variable costs are also higher for special needs students than variable costs for students without special needs. Information on staffing for special education suggests that the variable cost rate for students with special needs is likely higher than the variable cost rate for students without special needs.

Data on the number of children that receive special education services and personnel that provide special education services under Part B of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) were obtained from the U.S. Department of Education. The child-to-staff ratio for students with special needs in school year 2017–18 was 6.0. This ratio is lower than the 7.7 ratio of overall number of pupils per public school employee.24 This difference is indicative of the resources required to provide an adequate education for the population of special needs children and suggests that students with special needs have 30 percent more personnel than the typical student in the public school system. The analysis adjusts the overall variable cost rate upwards by 30 percent to generate variable cost estimates for students with special needs.

Students enrolled in in choice programs represent a diverse group of children with significantly varying needs for educational services. Thus, one limitation of the analysis is its reliance on state-level data to estimate educational costs. It follows that if the group of students using special needs vouchers are, on average, less disabled than the statewide distribution, then savings may be overestimated. Conversely, if the distribution of disabilities of students with special needs participating in an educational choice program skews toward more severe disabilities, then savings may be underestimated.

Overall Results

Table 2 shows the lower bound (short-run) and upper bound (long-run) estimates of the fiscal effects of the 40 educational choice programs studied. Based on lower bound estimates, most programs saved money. Based on upper bound estimates, all educational choice programs save taxpayers money. While the fiscal effects likely lie somewhere between the lower and upper estimates, results show that choice programs operating today produce substantial fiscal benefits for state and local taxpayers.

Lower bound estimates indicate that through FY 2018, educational choice generated at least $12.4 billion ($3,300 per student) in short-run cumulative net fiscal benefits for state and local taxpayers. For each dollar spent, programs generated at least $1.81 in net fiscal benefits. On average, for programs to produce net fiscal savings, at least 50 percent of students would need to be switchers.

Upper bound estimates indicate that programs generated up to $28.3 billion in cumulative net fiscal benefits for state and local taxpayers through FY 2018 (or up to $7,500 per student). Each dollar spent on choice programs generated up to $2.85 in net fiscal benefits for state and local taxpayers. On average, for programs to produce net fiscal savings, at least 32 percent of students would need to be switchers.

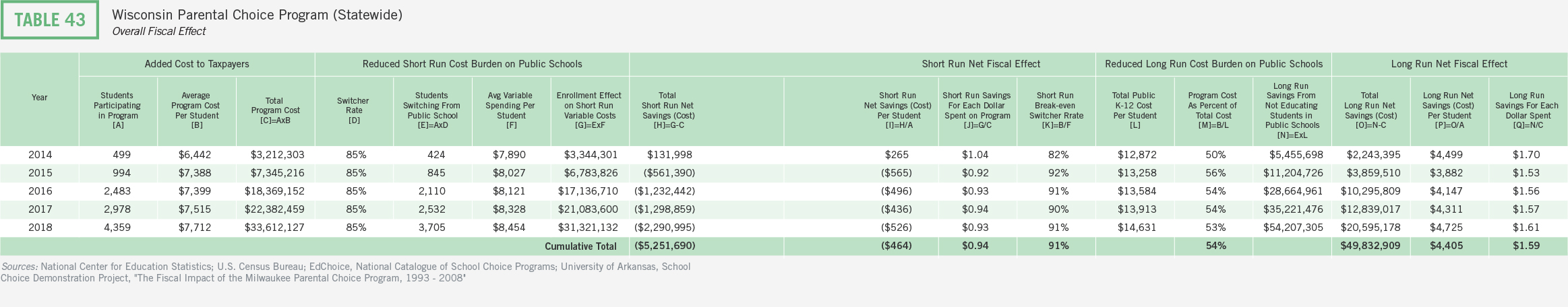

While most educational choice programs produce net fiscal savings in the short run, these fiscal effects differ across programs and across states. Lower bound estimates for four programs suggest estimated net cumulative costs in the short run. Three of these programs (Alabama’s program, Arizona’s ESA program, and Wisconsin’s statewide voucher program), however, have also been in operation for at least five years, respectively, suggesting that the actual fiscal effects are closer to the upper bound estimates.25

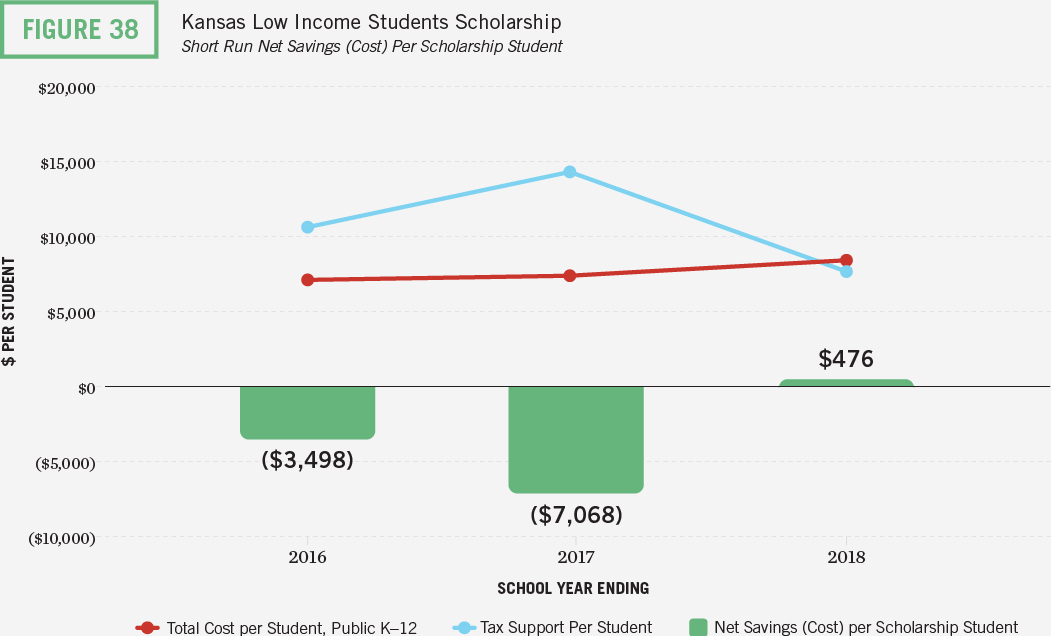

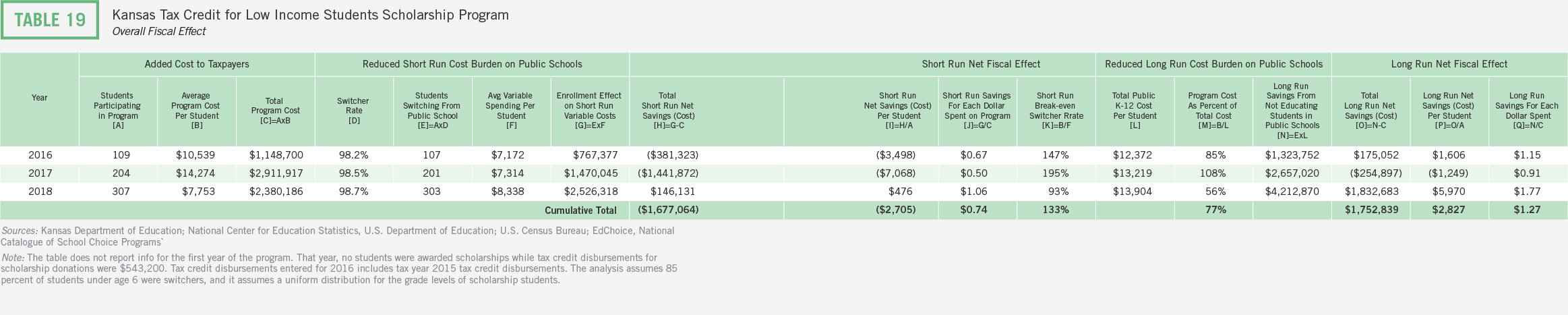

While Kansas’s tax-credit scholarship program generated an estimated small net cost for taxpayers during the program’s first three years, upper bound estimates suggest that the program will generate savings for Kansas taxpayers the longer the program operates.26 Another analysis of this program suggests that some programs may need more than three years to generate positive returns.27 Based on short-run fiscal effects estimates from that analysis, the program broke even by Year 4 and generated cumulative net fiscal savings by Year 5 estimated at $1.7 million, or $1,150 per scholarship student.28

Although Arizona’s ESA program and Wisconsin’s statewide voucher program also indicate net short-run costs, these states operate multiple educational choice programs (the analysis includes five programs in Arizona and three in Wisconsin). For these two states, lower bound estimates indicate that the net cumulative fiscal effects of their choice programs combined are positive, suggesting that educational choice overall is generating net savings for taxpayers even in the short run.

Table 3 aggregates fiscal effects estimates by state. Eleven of the 20 states in the study operate multiple educational choice programs. Overall, programs generated cumulative net fiscal benefits for 18 of the 20 states in the study. Alabama and Kansas, each with one tax-credit scholarship program, incurred small cumulative net costs overall in the short run from their programs through FY 2018.

Appendix Table 2 and Appendix Table 3 aggregates the fiscal effects by program years in operation and by program type.

Discussion

The distribution of fiscal effects across different taxpayers and school districts represents a complex question beyond the scope of this analysis.29 Under a system of fair school funding, where every public dollar follows a child to an educational setting of their family’s choosing, a choice program will be fiscally neutral for public schools and taxpayers in the long run overall. Most public school systems, however, allow districts to retain a portion of the per-student funding for students they no longer educate, and all students in choice programs receive less funding than they would have generated for their residentially assigned public school. Because the per-student cost of educational choice programs is significantly below the per-student cost of public school systems, choice programs generate net fiscal benefits overall when students choose to switch from public schools into the program.

Although this report focuses on the direct fiscal effects of choice program on taxpayers, programs provide potential indirect fiscal effects as well. For example, some research suggests that choice programs reduce crime, teen pregnancy, adolescent suicide rates, and mental health issues as adults.30 In light of these social benefits, this report’s fiscal effects estimates likely understate the total fiscal savings for taxpayers. Moreover, choice programs may keep some private schools open. If any private schools would close without choice programs in place, then many displaced students who are mostly private pay would likely migrate to the public schools and create a significant fiscal burden for taxpayers. Students participating in choice programs and students who remain in public schools also accrue benefits such as improvements in academic achievement, gains in learning, and improved civic outcomes.31 These benefits likely yield economic benefits for society, though the present analysis would not capture these benefits for taxpayers.

Conclusion

This report provides contextual information to help understand the fiscal effects of educational choice programs on taxpayers. As taxpayers pay both state and local taxes, the analysis estimates the fiscal effects of state and local taxpayers combined.

The report generates lower bound and upper bound estimates of the fiscal effects of educational choice programs on taxpayers through FY 2018. Programs generated net fiscal savings for taxpayers estimated between $12.4 billion and $28.3 billion (or between $3,300 and $7,500 per student participant). Taxpayers experienced between $1.80 and $2.85 in fiscal benefits for each dollar spent on choice programs.

The results from this fiscal analysis should not be surprising given that educational choice programs are funded at a significantly lower public expense than public school systems. While educational choice programs enroll just 2.3 percent of publicly funded K-12 students overall, these programs receive just 1.0 percent of total public spending. These basic facts provide important context for evaluating arguments that private educational choice programs harm students who remain in district schools.

Given this context, it is difficult to see how expanding educational opportunities for families via educational choice programs could harm public school systems fiscally. To be sure, many studies have examined educational choice programs’ effects on students enrolling in nearby public schools. Nearly all find that students who remain in district schools experience modest and positive gains in learning. Contrary to claims that students in district schools are harmed by increasing educational choice, the evidence suggests otherwise.

Fiscal Effects By Program

Alabama

PROGRAMS INCLUDED IN ANALYSIS

1. Alabama Education Scholarship Program

FISCAL EFFECTS SINCE INCEPTION OF PROGRAMS THROUGH FY 2018

Short Run Cumulative Net Savings (Cost): ($24.1 million)

Short Run Cumulative Net Savings (Cost) Per Student: ($1,299)

Short Run Savings for Each Dollar of Program Expenditure: $0.79

Long Run Cumulative Net Savings (Cost): $39.4 million

Long Run Cumulative Net Savings (Cost) Per Student: $2,127

Long Run Savings for Each Dollar of Program Expenditure: $1.34

EDUCATION SCHOLARSHIP PROGRAM

Plan parameters described below were in effect during FY 2018, the latest year in the analysis, and may not reflect provisions currently in place.

The Alabama Education Scholarship Program is a tax-credit scholarship program that disburses tax credits to taxpayers for donations to nonprofit scholarship-granting organizations (SGOs). SGOs determine the amount for scholarships. Scholarship awards may not exceed the lesser of private school tuition or $6,000 for grades K-5, $8,000 for grades 5-8, and $10,000 for grades 9-12.

Students are eligible to receive scholarships if they are below age 19 and qualify for the federal free and reduced-price lunch (FRL) program. Students may continue to participate in the program as long as their family’s income does not exceed 275 percent of the federal poverty level.

The program gives first priority to public and private school students assigned to failing schools. The state defines failing public schools if it is designated as failing by the state Superintendent of Education or if the school does not exclusively serve a special population of students and falls in the bottom 6 percent of public K–12 schools on the state’s standardized reading and math assessments.

If an SGO has scholarship funds unaccounted for on July 31 of each year, scholarships may be made available to eligible students in public school, regardless of whether their assigned public school is considered failing.

No more than 25 percent of first-time scholarship recipients to have already been enrolled in a private school the previous year. This rule implies a minimum switcher rate of 75 percent for the program each year. To estimate switcher rates, the analysis uses publicly reported information on the number of first-time scholarship recipients who were continuously enrolled in private school before entering the program.

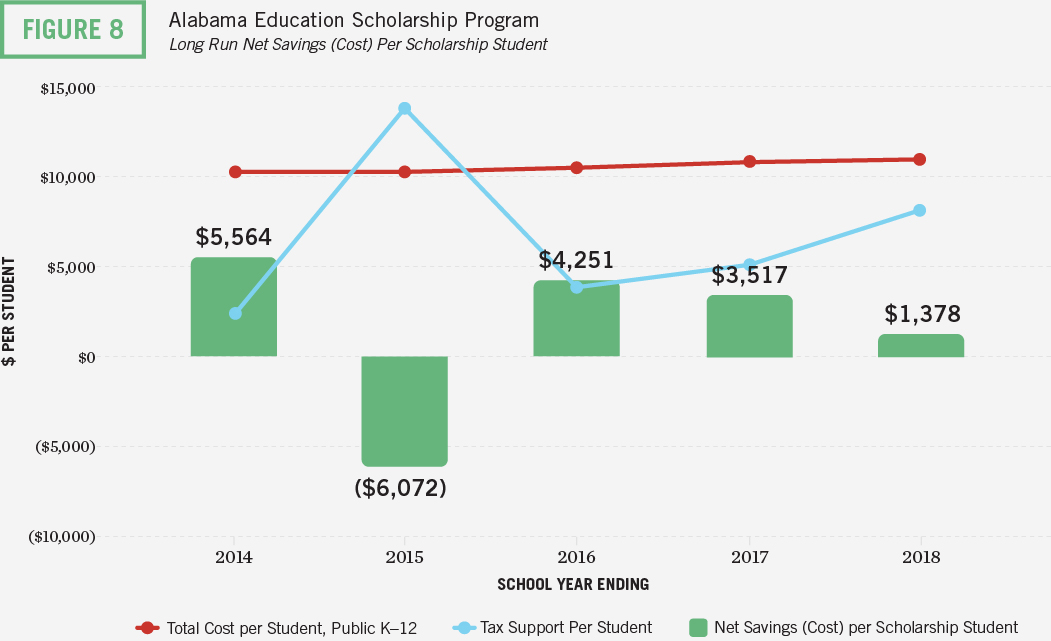

The program’s first year was unusual given the disparity between the large amount of tax credits disbursed for donatiosns and the small number of students participating in the program. This large imbalance differs from what we observe in tax-credit programs operating in other states. As a result, the program is one of just a few programs where the analysis estimated net fiscal costs in the short run.

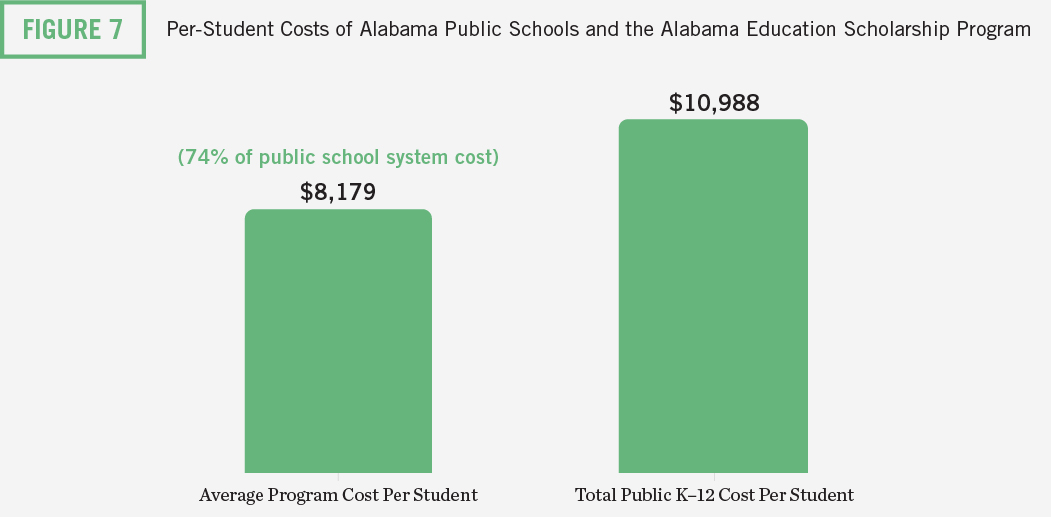

Fiscal Disparity for Education Scholarship Program

In Alabama, the estimated total cost of public schools per student in FY 2018 was $10,988 and the estimated average variable cost per student was $6,545. The average amount of tax credit disbursements was $8,179, or 74 percent of the total per-student cost for the public school system. The average per-student cost of the program is greater than the average per-student variable cost and indicates that that the program is generating a cost for taxpayers and school districts when students leave the public school system.

Fiscal Impact

Because the program has been in operation for six years, fiscal effects are likely closer to the upper bound estimates.

Lower bound estimates: Lower bound estimates suggest that in the short run, the Education Scholarship Program generated a cumulative net fiscal cost for Alabama taxpayers of $24 million, or $1,300 for each scholarship student through FY 2018. Put another way, for each dollar spent on the program, state and local taxpayers experienced $0.79 in cumulative savings. To save taxpayer dollars in the short run, over 90 percent of students would have to be switchers from public schools.

Upper bound estimates: Upper bound estimates suggest that in the long run, the Education Scholarship Program’s existence through FY 2018 saved Alabama taxpayers $39 million, or about $2,100 for each scholarship student. Put another way, for each dollar spent on the program, state and local taxpayers would experience $1.34 in cumulative savings. To save taxpayer dollars in the long run, over 60 percent of students would have to be switchers from public schools.

Arizona

PROGRAMS INCLUDED IN ANALYSIS:

1. Arizona Empowerment Scholarship Accounts

2. Arizona Original Individual Income Tax Credit Scholarship Program

3. Arizona Low-Income Corporate Income Tax Credit Scholarship Program

4. Arizona Lexie’s Law for Disabled and Displaced Students Tax Credit Scholarship Program

5. Arizona “Switcher” Individual Income Tax Credit Scholarship Program

FISCAL EFFECTS SINCE INCEPTION OF PROGRAMS THROUGH FY 2018

Short Run Cumulative Net Savings (Cost): $1.2 billion

Short Run Cumulative Net Savings (Cost) Per Student: $1,861

Short Run Savings for Each Dollar of Program Expenditure: $1.73

Long Run Cumulative Net Savings (Cost): $3.2 billion

Long Run Cumulative Net Savings (Cost) Per Student: $4,808

Long Run Savings for Each Dollar of Program Expenditure: $2.88

EMPOWERMENT SCHOLARSHIP ACCOUNTS

Plan parameters described below were in effect during FY 2018, the latest year in the analysis, and may not reflect provisions currently in place.

Launched in 2011, Arizona’s Empowerment Scholarship Accounts (ESA) program is the first education savings account program started in the United States. It allows parents to withdraw their children from district or charter schools and receive a portion of their public funding deposited into an account with defined, but multiple, uses, including private school tuition, online education, private tutoring or future educational expenses.

To be eligible for the program, students must have previously attended a public school for at least 100 days or are eligible to enroll in kindergarten. They must also meet one of the following criteria:

• received a scholarship from a school tuition organization (STO) under Lexie’s Law,

• attended a “D” or “F” letter-grade school or school district,

• been adopted from the state’s foster care system,

• is already an ESA recipient, or

• live on a Native American reservation.

Children of parents who are legally blind, deaf or hard of hearing, and siblings of current or previous ESA recipients are also eligible for the program provided they meet the public school prior enrollment requirement. Children of active-duty military members or whose parents were killed in the line of duty, and preschool children with special needs are exempt from the public school prior enrollment requirement.

Students in households that earn up to 250 percent of poverty will receive ESAs funded at 100 percent of the base for whichever school type the student previously attended (charter or district). All other students in the program receive ESAs funded at 90 percent of the same per-student base funding. Students with special needs receive additional funding depending on the services the student’s disability requires.

In its first year, the ESA program was open solely to students with special needs. In 2015, the program opened up to students in kindergarten, D/F districts, active duty military families, and foster care. The analysis assumes that all students participating in the ESA program are switchers through FY 2014. For 2015 and after, it applies an 85 percent switcher rate to the proportion of students in categories exempt from the public school requirement.

School choice programs that serve students with special needs present a unique challenge for estimating their fiscal effects. Not only are educational costs for students with special higher than the education costs for students without special needs, but the costs for students with special needs vary significantly depending on the severity of students’ disabilities. Therefore, the average variable cost for any group of students using ESAs will be unique to that group and determined by the types/severity of disabilities in that group. Compared to the statewide average variable cost for all students with special needs, the average variable cost for students using ESAs may differ by a little or a lot. The ESA program is designed so that the ESA amounts and the per-student variable costs vary together. Students with severe disabilities can receive larger ESA amounts. As the ESA cost increases, the cost burden relieved from the public school system rises proportionally.

Nearly 60 percent of students participating in the program in FY 2018 were students with special needs. The analysis accounts for the higher cost of serving this group (see the methods section in the main report for details). Within the group of students with disabilities in the ESA program, almost two-thirds either had multiple disabilities or had autism. The analysis also accounts for the higher cost of these groups relative to students with other special needs. We have information about the distribution of students by disability for FY 2016 and FY 2018.i This information allows us to generate more precise estimates for the educational costs for this group of students. The analysis applies the same weights to prior years, although it’s likely the case that the shares of students with and without disabilities, and the distribution of students by disability, were different in earlier years.

The program is open to other students from disadvantaged circumstances who do not have disabilities. While the educational costs for these students will be higher than students without those characteristics due to their disadvantaged circumstances, there is insufficient information to account for these differential costs. As such, the analysis takes a cautious approach by not adjusting estimated educational costs upwards for ESA students without special needs who have other disadvantaged circumstances.

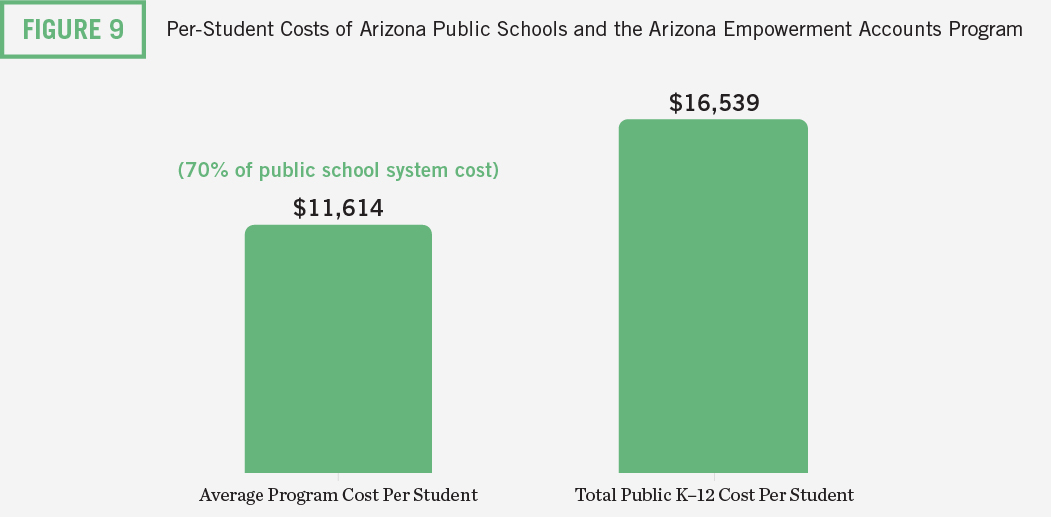

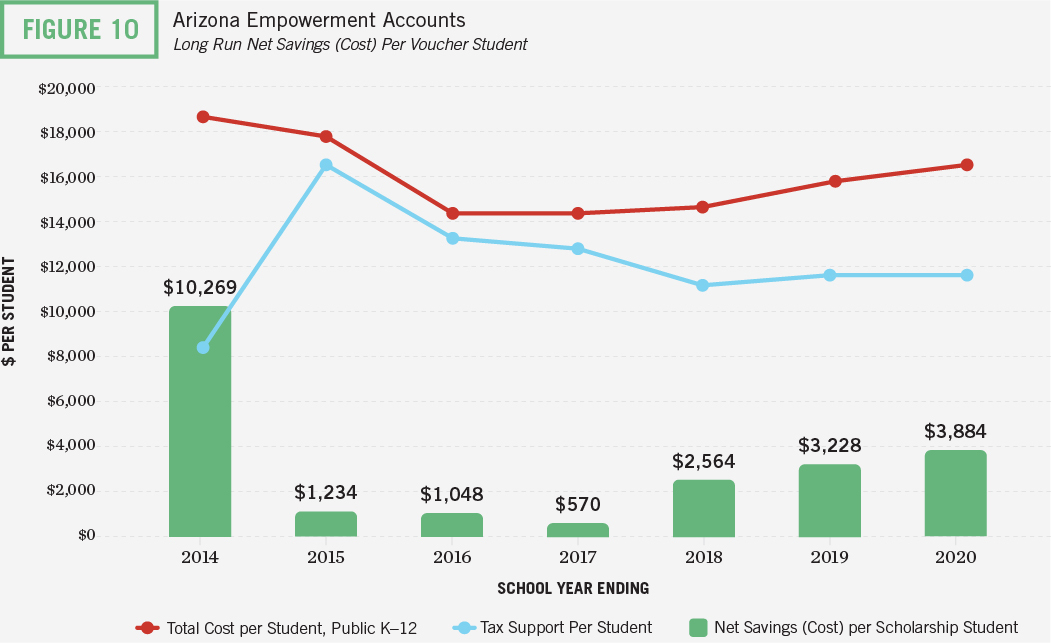

Fiscal Disparity for Empowerment Scholarship Accounts

In Arizona, the estimated average total cost of public schools per student for students in the ESA program in FY 2018 was $16,539 and the estimated average variable cost per student for students in the ESA program was $12,078. The average ESA amount was $11,614, or 70 percent of the total per-student cost to educate these students in the public school system. The average per-student cost of the program is lower than the estimated average per-student variable cost and indicates that that the program generates fiscal benefits for taxpayers and school districts when students leave the public school system.

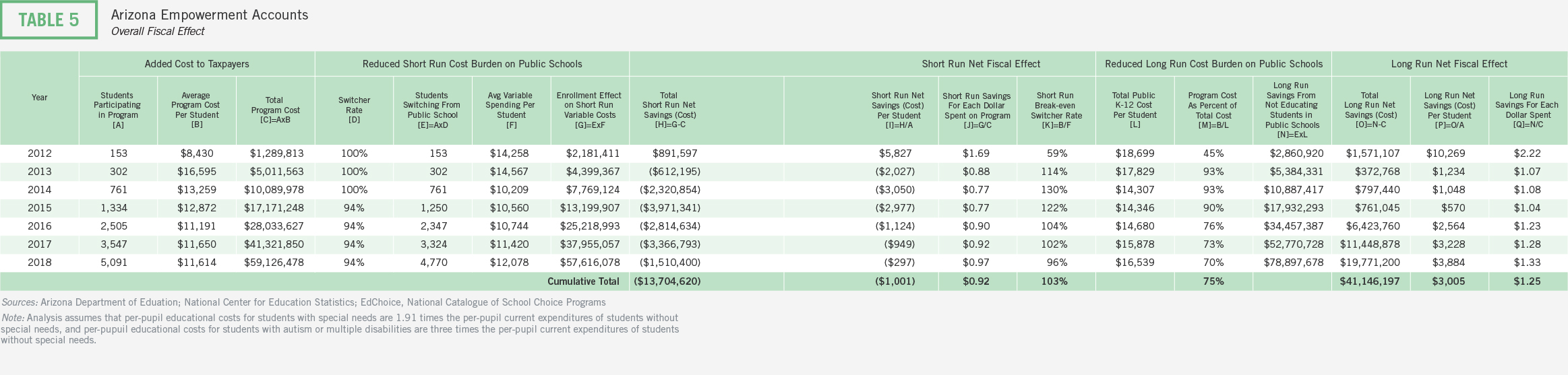

Fiscal Impact

Because the program has been in operation for seven years, fiscal effects are likely closer to the upper bound estimates.

Lower bound estimates: Lower bound estimates suggest that in the short run, the Empowerment Scholarship Accounts generated net costs for Arizona taxpayers of about $13.7 million, or about $1,000 for each ESA recipient through FY 2018. Put another way, for each dollar spent on the program, state and local taxpayers experienced $0.92 in cumulative savings. A break-even point does not emerge in the short run.

Upper bound estimates: Upper bound estimates suggest that in the long run, the Empowerment Scholarship Accounts program’s existence through FY 2018 saved taxpayers $41 million, or about $3,000 for each ESA recipient. Put another way, for each dollar spent on the program, taxpayers would experience $1.25 in cumulative savings. To save taxpayer dollars in the long run, over 75 percent of students would have to be switchers from public schools.

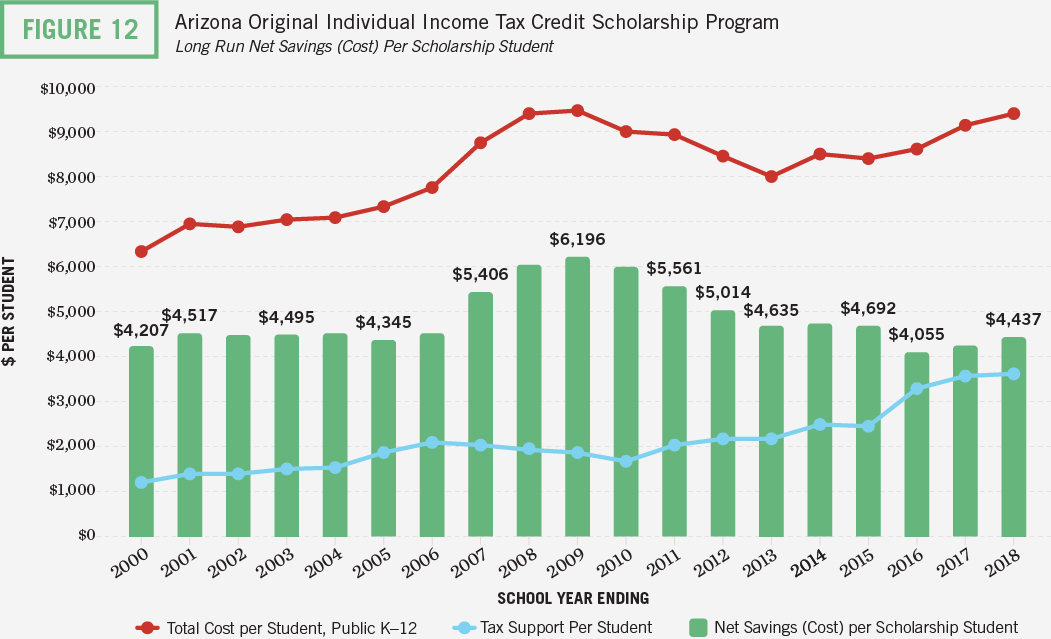

ORIGINAL INDIVIDUAL INCOME TAX CREDIT SCHOLARSHIP PROGRAM

Plan parameters described below were in effect during FY 2018, the latest year in the analysis, and may not reflect provisions currently in place.

Arizona has four tax-credit scholarship programs. The Original Individual Income Tax Credit Scholarship Program is the oldest in the United States and universal in terms of eligibility. Students in grades K–12 or prekindergarten students identified with a disability under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act or Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act are eligible for the program. That means all Arizona K–12 students are eligible, regardless of where they enrolled prior to participating in the program and makes the program the most accessible tax-credit scholarship program in the country.

Individuals may make donations to School Tuition Organizations (STOs) and receive a dollar-for-dollar tax credit. For tax year 2017, single filers could claim up to $546, while married couples filing jointly could claim up to $1,092. The maximum amount of credits claimable increases each year per the Consumer Price Index. There is also no limit to the amount of credits granted by state governments. Scholarship amounts are determined by the STOs and are not limited.

Growth in the nation’s oldest tax-credit scholarship program was substantial in the early years of its existence and steady in recent years. It can take a few years before a positive fiscal impact is realized—especially when existing private school students are eligible. In the first two years, the amount of donations to the program were substantially disproportionate to the number of scholarships awarded. Subsequently, the average tax support was quite high in those years, leading to net negative fiscal impacts during those two years. Average tax support normalized by the third year.

To account for the possibility that some students would have enrolled in non-public schools without the program in place, the analysis uses information from lottery-based studies of voucher programs to inform switcher rates.ii Lower bound and upper bound median and weighted average switcher rate estimates were about 85 percent and 90 percent, respectively. The analysis for the Low-Income program cautiously assumes 85 percent for the switcher rate in the program.

Government agencies that report data on the state’s tax-credit scholarship programs disclose the number of scholarships awarded but do not track the number of students participating in the program. These numbers can differ because students may receive more than one scholarship from different SGOs or participate in more than one program. For these reasons, the analysis makes adjustments to account for multi-scholarship students.iii Without these adjustments, the estimated total number of scholarships awarded to students in these programs combined would exceed the total number of students enrolled in private schools.iv

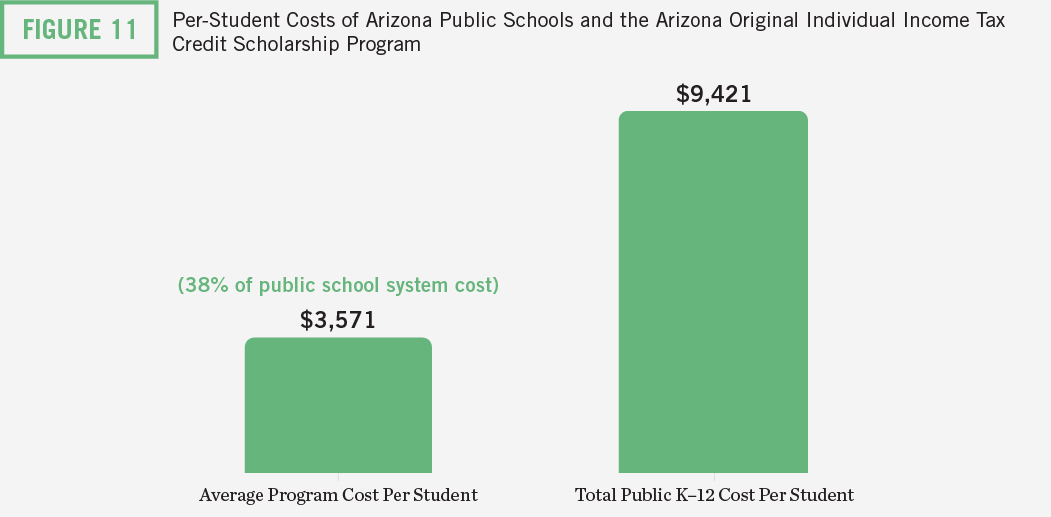

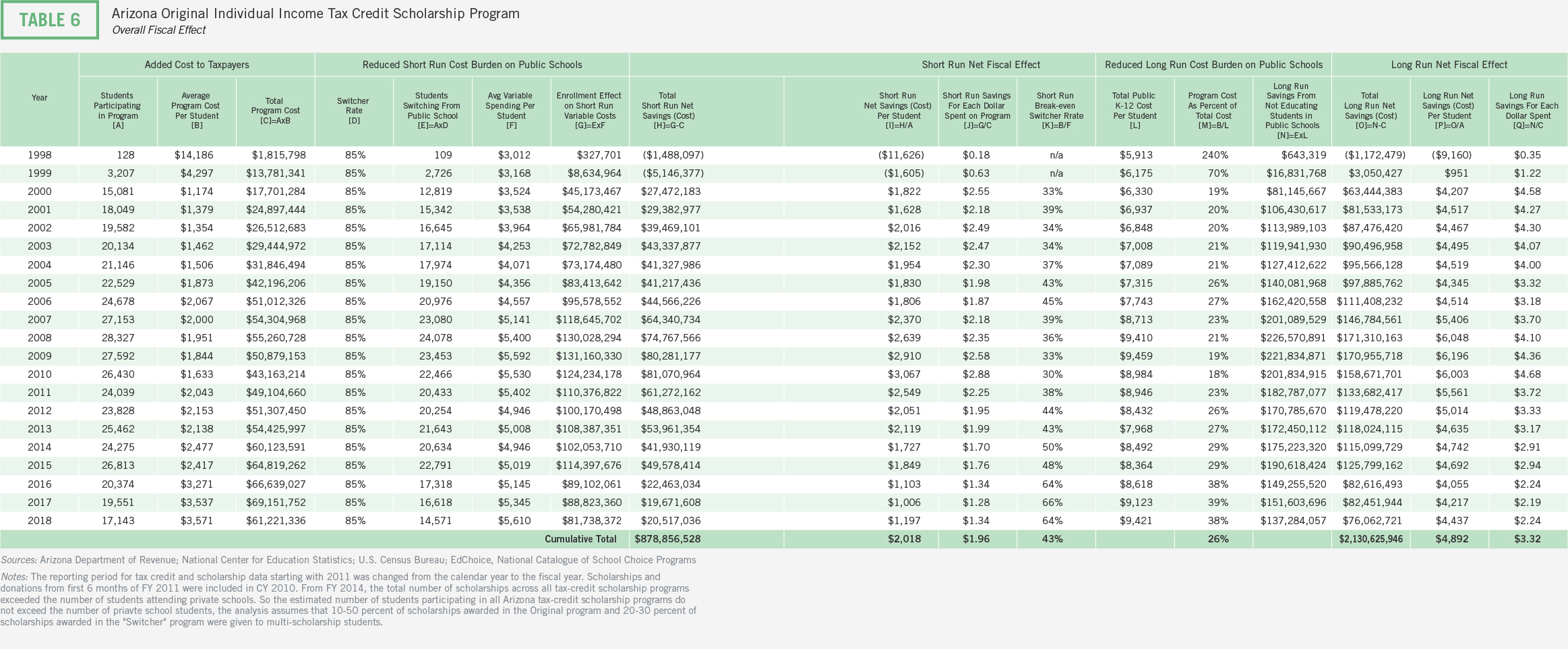

Fiscal Disparity for Original Individual Income Tax Credit Scholarship Program

In Arizona, the estimated total cost of public schools per student in FY 2018 was $9,421 and the estimated average variable cost per student was $5,610. The average amount of tax credit disbursements was $3,571, or just 38 percent of the total per-student cost for the public school system. The average per-student cost of the program is significantly less than the average per-student variable cost and indicates that that the program is generating cost savings for taxpayers and school districts when students leave the public school system.

Fiscal Impact

Because the program has been in operation for 21 years, fiscal effects are likely closer to the upper bound estimates.

Lower bound estimates: Lower bound estimates suggest that in the short run, the Original Individual Income Tax Credit Scholarship Program generated $879 million in cumulative net fiscal benefits for Arizona taxpayers, or about $2,000 for each scholarship student through FY 2018. Put another way, for each dollar spent on the program, state and local taxpayers experienced $1.96 in cumulative savings. To save taxpayer dollars in the short run, over 43 percent of students would have to be switchers from public schools.

Upper bound estimates: Upper bound estimates suggest that in the long run, the Original Individual Income Tax Credit Scholarship Program’s existence through FY 2018 saved Arizona taxpayers $2.1 billion, or about $4,900 for each scholarship student. Put another way, for each dollar spent on the program, state and local taxpayers would experience $3.32 in cumulative savings. To save taxpayer dollars in the long run, over 26 percent of students would have to be switchers from public schools.

LOW-INCOME CORPORATE INCOME TAX CREDIT SCHOLARSHIP PROGRAM

Plan parameters described below were in effect during FY 2018, the latest year in the analysis, and may not reflect provisions currently in place.

The Corporate Income Tax Credit Scholarship Program allows STOs to receive donations earmarked for granting scholarships to students from low-income families—up to 185 percent of eligibility for the federal free and reduced-price lunch program. Students must also meet one of the following criteria:

• is enrolled in kindergarten

• is enrolled in a program for students with disabilities

• was previously enrolled in a public school for at least 90 days during the previous year or a full semester during the current school year

• is a dependent of an active-duty member of the military stationed in Arizona

• is a prior recipient of this program or the Individual Tax Credit Program

State governments give tax credits on a dollar-for-dollar basis to corporations making donations to STOs. While there is no limit to how much a corporation may donate to an STO, the maximum tax credits the state could grant in 2018 was $102.5 million. This cap increases annually until 2022-23. The scholarship amount was also capped at $5,300 for grades K–8 and $6,600 for grades 9–12.

Students with special needs are also eligible for this scholarship. To be overly cautious, we assume that no students with disabilities leave public schools to participate in this program. To the extent that some switchers have disabilities, estimated savings will be understated given the higher cost associated with this group.

While prior enrollment in a public school is a requirement for program eligibility, there are notable exceptions to this requirement including kindergarten students, students enrolled in a private school program for students with disabilities, and students who previously participated in the Individual Tax Credit Program. Given these exceptions to the public school prior enrollment requirement, it is possible that some scholarship recipients would enroll in private school even without the program’s financial assistance. It is impossible to know exactly how many students in the program would be switchers, however, and data on prior enrollment are not available.

To account for the possibility that some students would have enrolled in non-public schools without the program in place, the analysis uses information from lottery-based studies of voucher programs to inform switcher rates.v Lower bound and upper bound median and weighted average switcher rate estimates were about 85 percent and 90 percent, respectively. The present analysis cautiously assumes 85 percent for the switcher rate in the program.

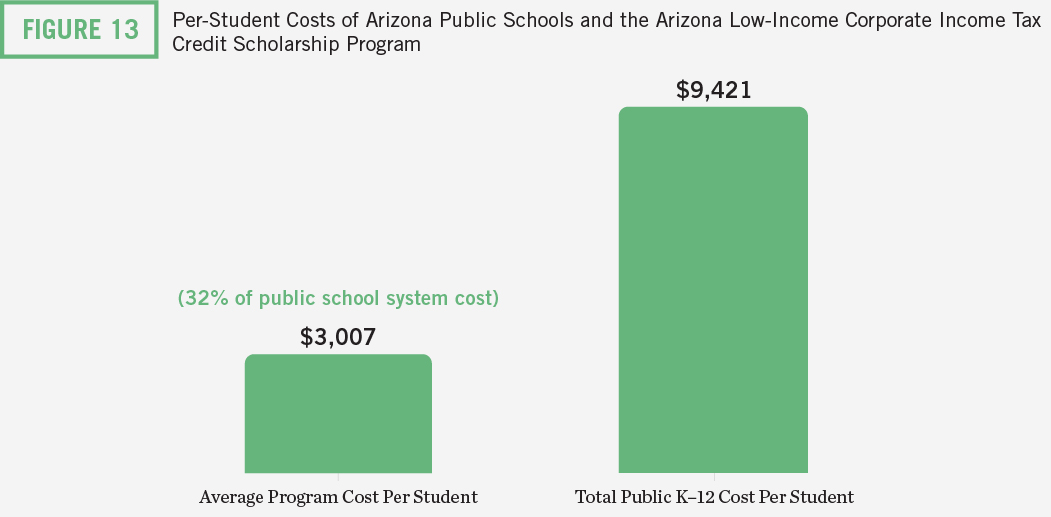

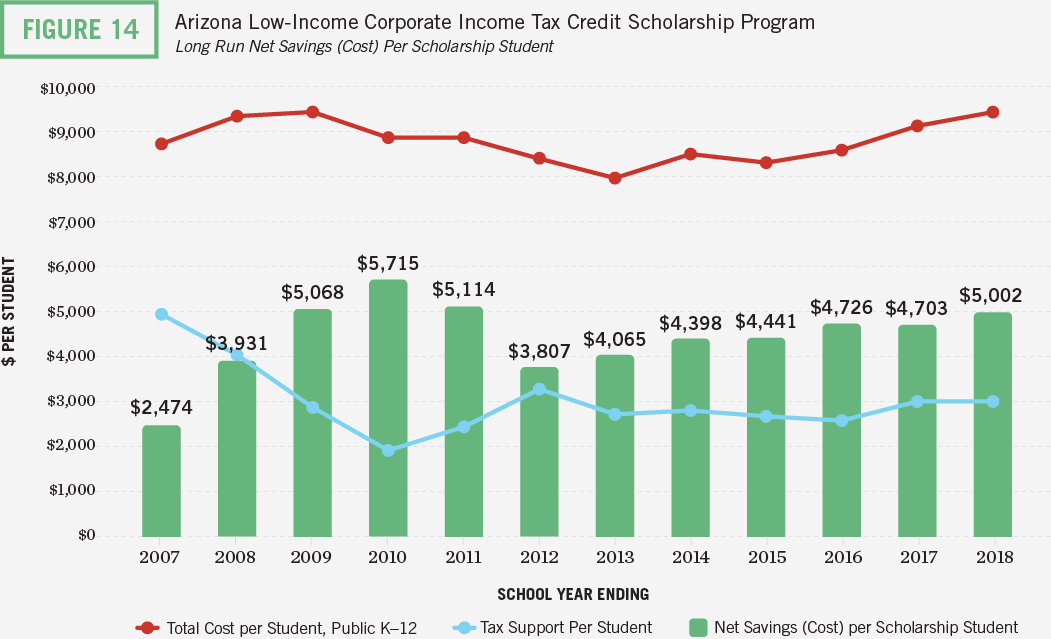

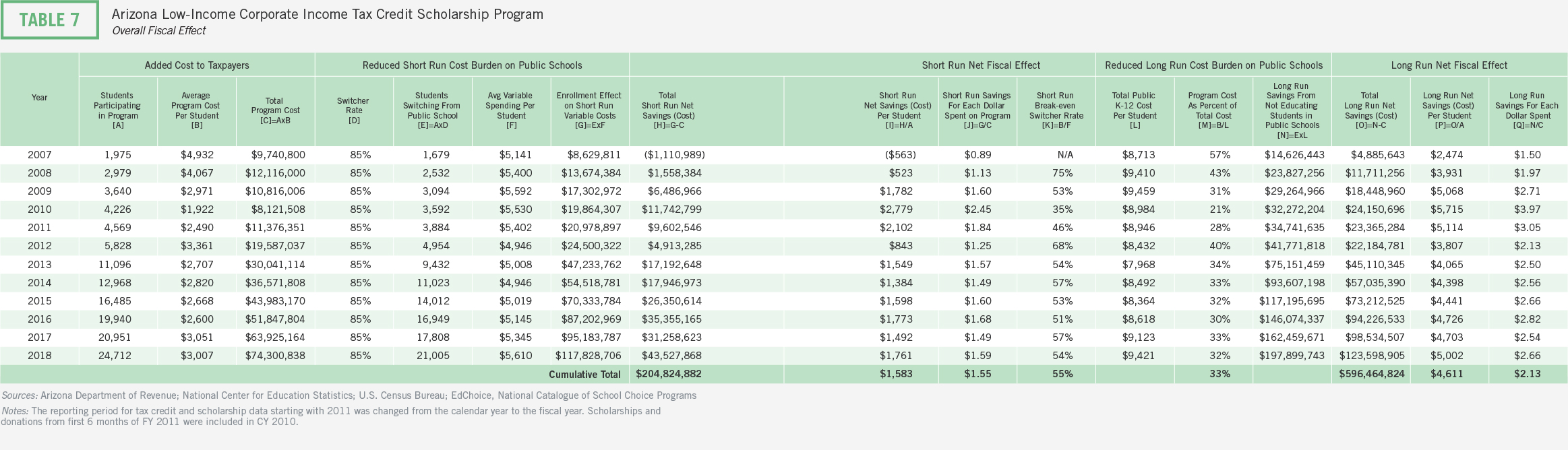

Fiscal Disparity for Low-Income Corporate Income Tax Credit Scholarship Program

In Arizona, the estimated total cost of public schools per student in FY 2018 was $9,421 and the estimated average variable cost per student was $5,610. The average amount of tax credit disbursements was $3,007, or just 32 percent of the total per-student cost for the public school system. The average per-student cost of the program is less than the average per-student variable cost and indicates that that the program is generating cost savings for taxpayers and school districts when students leave the public school system.

Fiscal Impact

Because the program has been in operation for 13 years, fiscal effects are likely closer to the upper bound estimates.

Lower bound estimates: Lower bound estimates suggest that in the short run, the Low-Income Corporate Income Tax Credit Scholarship Program generated $205 million in cumulative net fiscal benefits for Arizona taxpayers, or about $1,600 for each scholarship student through FY 2018. Put another way, for each dollar spent on the program, state and local taxpayers experienced $1.55 in cumulative savings. To save taxpayer dollars in the short run, over 55 percent of students would have to be switchers from public schools.

Upper bound estimates: Upper bound estimates suggest that in the long run, the Low-Income Corporate Income Tax Credit Scholarship Program’s existence through FY 2018 saved Arizona taxpayers $596 million, or about $4,600 for each scholarship student. Put another way, for each dollar spent on the program, state and local taxpayers experienced $2.13 in cumulative savings. To save taxpayer dollars in the long run, over 33 percent of students would have to be switchers from public schools.

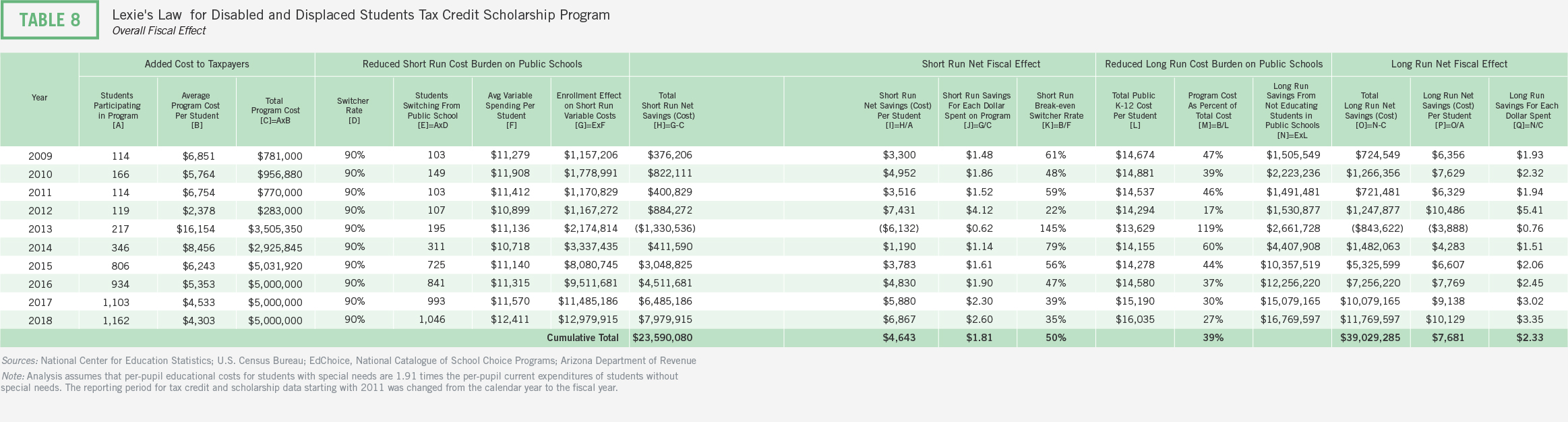

LEXIE’S LAW FOR DISABLED AND DISPLACED STUDENTS TAX CREDIT SCHOLARSHIP PROGRAM

Plan parameters described below were in effect during FY 2018, the latest year in the analysis, and may not reflect provisions currently in place.

Lexie’s Law was enacted to help Arizona children in foster care and children with disabilities receive educational services in a private school. To be eligible, students must have a Multidisciplinary Evaluation Team (MET) or Individualized Education Plan from an Arizona public school district, a 504 plan from an Arizona public school district, or have ever been in the Arizona foster care system.

Scholarships in the Lexie’s Law program are completely funded by donations from corporations. Donors receive a dollar tax credit for each dollar donated to an STO. Though there is no limit on the amount of donations that may be made, the budget for the program is capped at $5 million dollars per year. Scholarship amounts are capped at the lesser of private school tuition or 90 percent of the state funding for a student’s residentially assigned public school.

Although it is possible that some students participating in the program would have enrolled in a non-public school setting without financial assistance from the program, this number is likely to be very small given their disadvantaged background and higher education costs. The analysis takes a very cautious approach by assuming that 90 percent students in the program are switchers. The analysis also accounts for the differential cost of providing services to students with special needs. The methods section in the main report discusses further details.

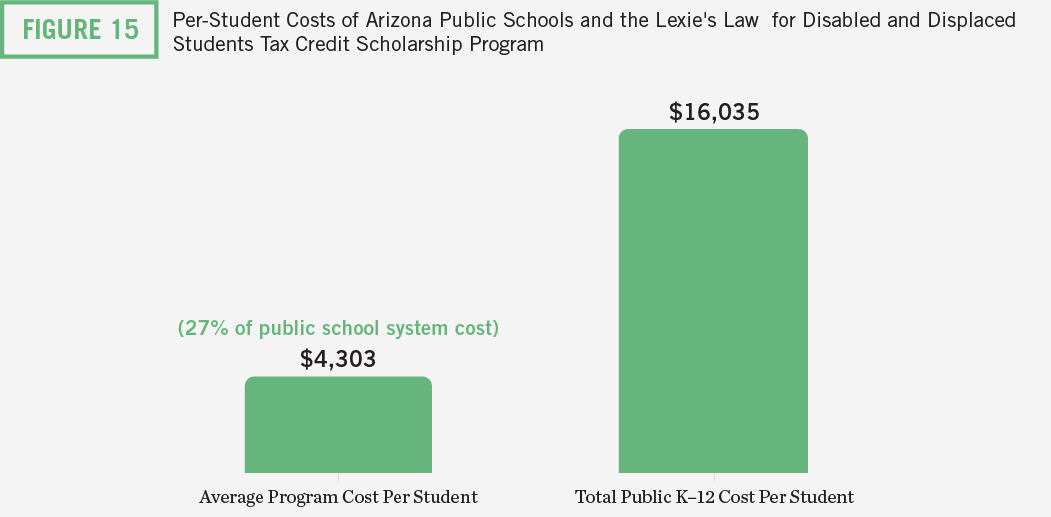

Fiscal Disparity for Lexie’s Law

In Arizona, the estimated total cost of public schools per student for students with special needs in FY 2018 was $16,035 and the estimated average variable cost per student for students with special needs was $12,411. The average amount of tax credit disbursements was $4,303, or just 27 percent of the total per-student cost for the public school system. The average per-student cost of the program is significantly less than the average per-student variable cost and indicates that that the program is generating cost savings for taxpayers and the district.

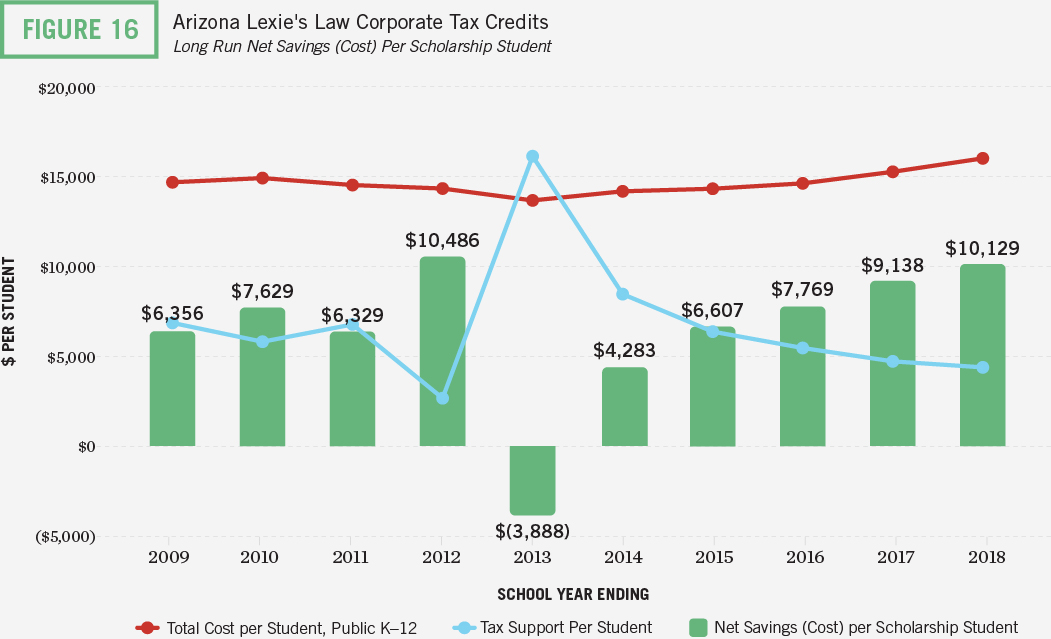

Fiscal Impact

Because the program has been in operation for 10 years, fiscal effects are likely closer to the upper bound estimates.

Lower bound estimates: Lower bound estimates suggest that in the short run, Lexie’s Law generated $24 million in cumulative net fiscal benefits for Arizona taxpayers, or about $4,600 for each scholarship student through FY 2018. Put another way, for each dollar spent on the program, state and local taxpayers experienced $1.81 in cumulative savings. To save taxpayer dollars in the short run, over 50 percent of students would have to be switchers from public schools.

Upper bound estimates: Upper bound estimates suggest that in the long run, Lexie’s Law’s existence through FY 2018 saved Arizona taxpayers $39 million, or about $7,700 for each scholarship student. Put another way, for each dollar spent on the program, state and local taxpayers would experience $2.33 in cumulative savings. To save taxpayer dollars in the long run, over 39 percent of students would have to be switchers from public schools.

“SWITCHER” INDIVIDUAL INCOME TAX CREDIT SCHOLARSHIP PROGRAM

Plan parameters described below were in effect during FY 2018, the latest year in the analysis, and may not reflect provisions currently in place.

The “Switcher” program is the newest of Arizona’s four tax-credit scholarship programs. To be eligible for the program, students must meet one of the following criteria:

• has previously attended a public school for at least a full semester or at least 90 days

• has enrolled in preschool and identified by the school district as having a disability under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act or Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act

• enrolled in kindergarten

• has a parent who is an active-duty military member stationed in Arizona

• is a previous recipient of a Low-Income Corporate Income Tax Credit Scholarship or “Switcher” Individual Income Tax Credit Scholarship who have remained in private school

Although the program is not means-tested, STOs must consider financial need when awarding scholarships. Program rules prevent STOs from making decisions based on donor recommendations and individual donors from making contributions earmarked for their own dependents. Moreover, donors may not “trade” donations for their respective dependents.

The “Switcher” program was created as a supplement to the Original Individual Income Tax Credit Scholarship Program for individual taxpayers who claim the maximum credit amount from the Original program. These individuals may subsequently make donations to STOs in the “Switcher” program in return for a dollar-for-dollar tax credit worth up to $546 for single filers and $1,092 for married couples filing jointly in 2018.

Generally, STOs receive donations from the “Switcher” program late in a calendar year, so they distribute scholarships from those funds in the following year. This lag in receipt versus payout is common. Because of this lag, the amount of donations to the program in the first year was highly disproportionate to the number of scholarships awarded. Subsequently, the average tax support was quite high in these years, leading to net negative fiscal impacts during the first year and a small fiscal benefit in the second year. Average tax support smoothed out from the third year.

While prior enrollment in a public school is a requirement for program eligibility, there are notable exceptions to this requirement including kindergarten students and students who previously participated in the Individual Tax Credit Program. Given these exceptions to the public school prior enrollment requirement, it is possible that some scholarship recipients would enroll in private school even without the program’s financial assistance. It is impossible to know exactly how many students in the program would be switchers, however, and data on prior enrollment are not available.

To account for the possibility that some students would have enrolled in non-public schools without the program in place, the analysis uses information from lottery-based studies of voucher programs to inform switcher rates.vi Lower bound and upper bound median and weighted average switcher rate estimates were about 85 percent and 90 percent, respectively. The analysis for the “Switcher” program cautiously assumes 85 percent for the switcher rate in the program.

Government agencies that report data on the state’s tax-credit scholarship programs disclose the number of scholarships awarded. They do not track the number of students participating in the program. These numbers can differ because students may receive more than one scholarship from different SGOs or participate in more than one program. For these reasons, the analysis makes adjustments to account for multi-scholarship students. These adjustments are necessary to ensure that the estimated total number of scholarship students participating in these programs combined do not exceed the total number of students enrolled in private schools.vii

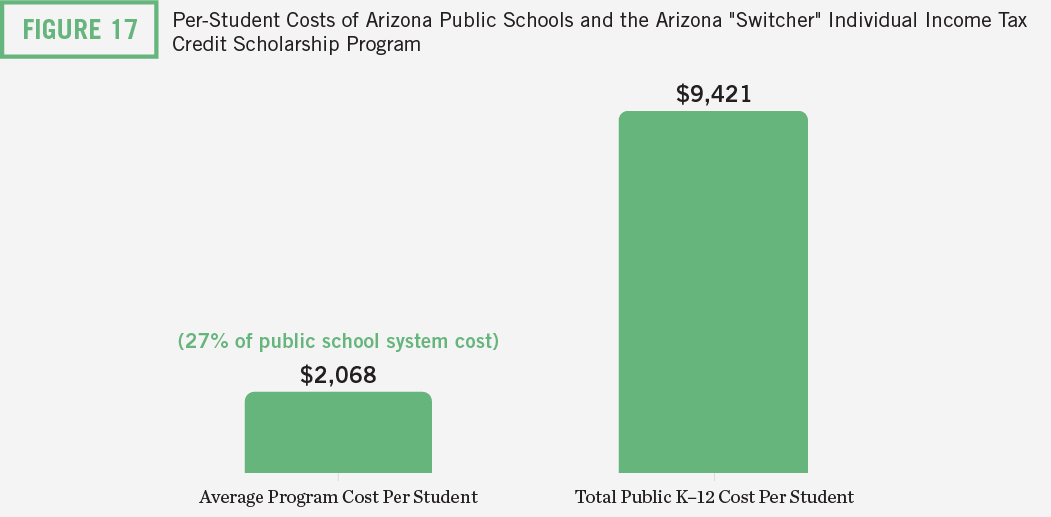

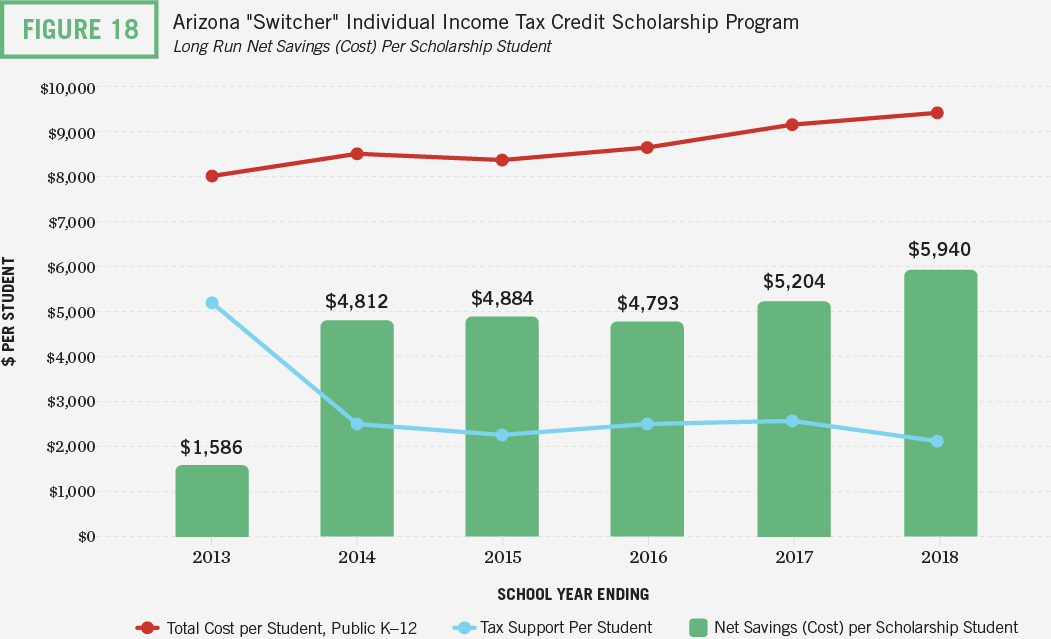

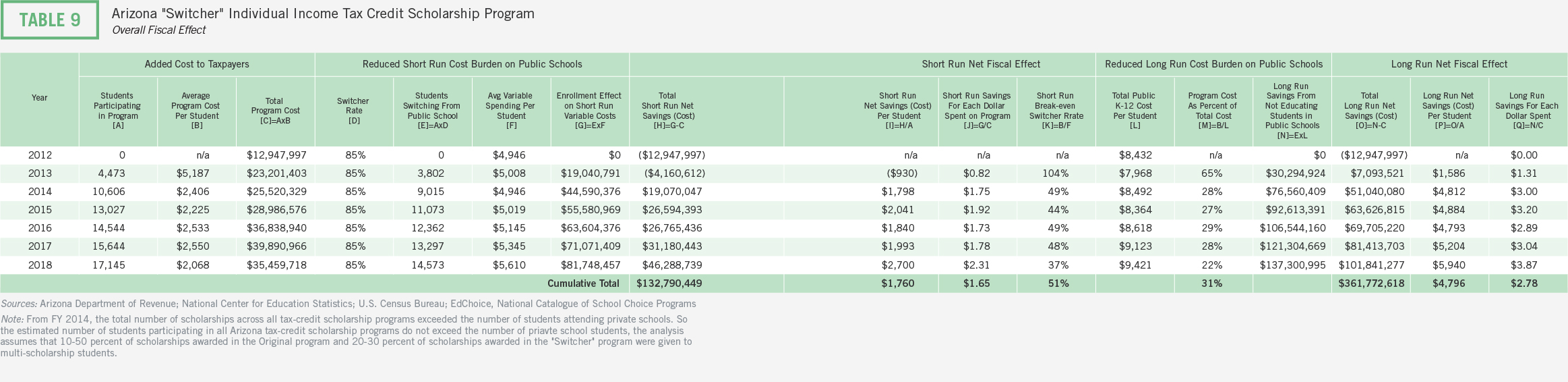

Fiscal Disparity for “Switcher” Program

In Arizona, the estimated total cost of public schools per student in FY 2018 was $9,421 and the estimated average variable cost per student was $5,610. The average amount of tax credit disbursements was $2,068, or just 22 percent of the total per-student cost for the public school system. The average per-student cost of the program is less than the average per-student variable cost and indicates that that the program is generating cost savings for taxpayers and school districts when students leave the public school system.

Fiscal Impact

Because the program has been in operation for seven years, fiscal effects are likely closer to the upper bound estimates.

Lower bound estimates: Lower bound estimates suggest that in the short run, the “Switcher” Individual Income Tax Credit Scholarship Program generated $133 million in cumulative net fiscal benefits for Arizona taxpayers, or about $1,800 for each scholarship student through FY 2018. Put another way, for each dollar spent on the program, state and local taxpayers experienced $1.65 in cumulative savings. To save taxpayer dollars in the short run, over 51 percent of students would have to be switchers from public schools.

Upper bound estimates: Upper bound estimates suggest that in the long run, the “Switcher” Individual Income Tax Credit Scholarship Program’s existence through FY 2018 saved Arizona taxpayers $362 million, or about $4,800 for each scholarship student. Put another way, for each dollar spent on the program, state and local taxpayers would experience $2.78 in cumulative savings. To save taxpayer dollars in the long run, over 31 percent of students would have to be switchers from public schools.

i The Goldwater Institute provided these data, which they originally received from the Arizona Department of Education.

ii For a summary, please see: Martin F. Lueken (2020), The Fiscal Impact of K-12 Educational Choice: Using Random Assignment Studies of Private School Choice Programs to Infer Student Switcher Rates, Journal of School Choice, published online 3/4/2020 at https://doi.org/10.1080/15582159.2020.1735863

iii From FY 2014 for each year, the analysis assumes that 10-50 percent of scholarships awarded in the Original program and 20-30 percent of scholarships awarded in the “Switcher” program were given to multi-scholarship students. For fiscal years 2016-2018, estimates for the number of scholarship students are close to 100 percent of the state’s private school enrollment.

iv For instance, in FY 2018 the total combined number of scholarships granted to students participating in any of the 4 programs was 85,175 and nearly doubled the 48,039 total students enrolled in private schools.

v For a summary, please see: Martin F. Lueken (2020), The Fiscal Impact of K-12 Educational Choice: Using Random Assignment Studies of Private School Choice Programs to Infer Student Switcher Rates, Journal of School Choice, published online 3/4/2020 at https://doi.org/10.1080/15582159.2020.1735863

vi For a summary, please see: Martin F. Lueken (2020), The Fiscal Impact of K-12 Educational Choice: Using Random Assignment Studies of Private School Choice Programs to Infer Student Switcher Rates, Journal of School Choice, published online 3/4/2020 at https://doi.org/10.1080/15582159.2020.1735863

vii From FY 2014 for each year, the analysis assumes that 10-50 percent of scholarships awarded in the Original program and 20-30 percent of scholarships awarded in the “Switcher” program were given to multi-scholarship students. For fiscal years 2016-2018, estimates for the number of scholarship students are close to 100 percent of the state’s private school enrollment.

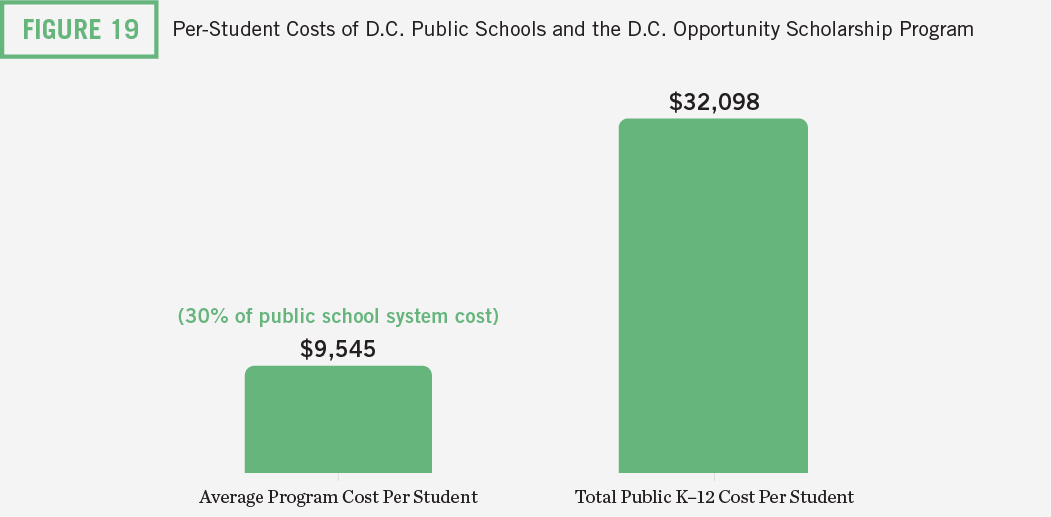

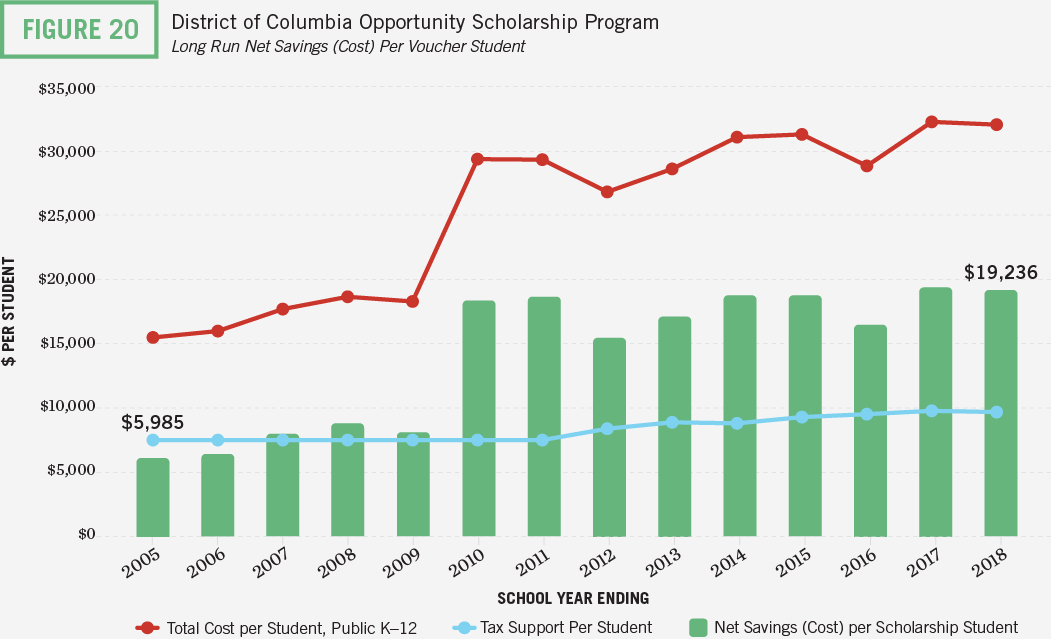

District of Columbia

PROGRAMS INCLUDED IN ANALYSIS:

1. D.C. Opportunity Scholarship Program

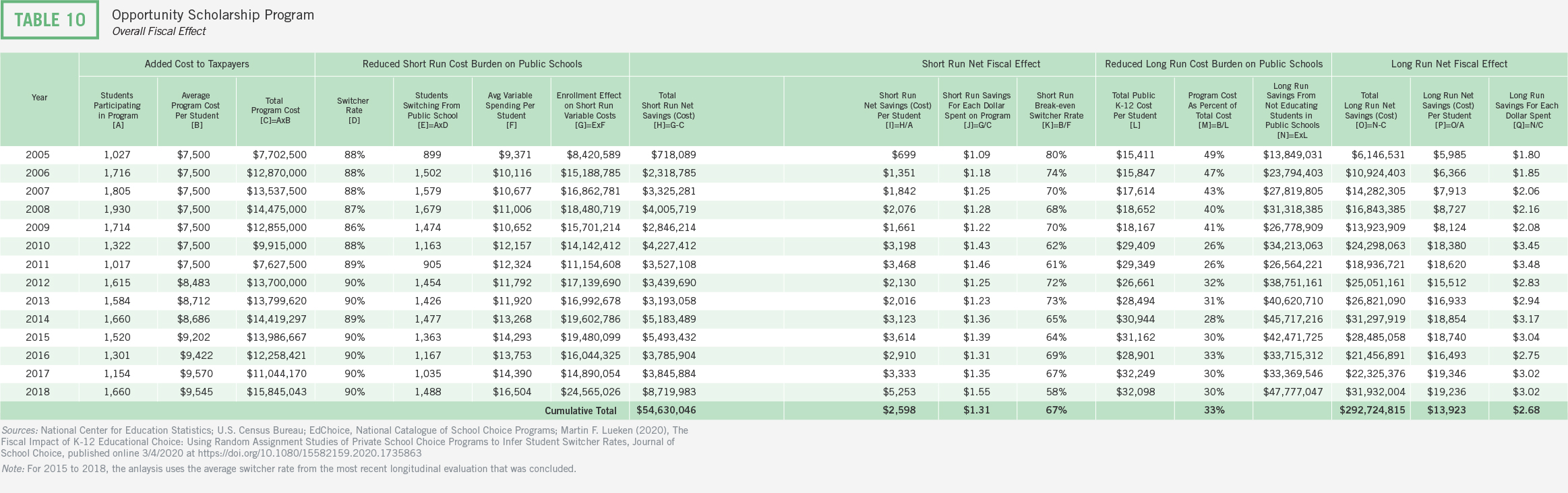

FISCAL EFFECTS SINCE INCEPTION OF PROGRAMS THROUGH FY 2018

Short Run Cumulative Net Savings (Cost): $54.6 million

Short Run Cumulative Net Savings (Cost) Per Student: $2,598

Short Run Savings For Each Dollar of Program Expenditure: $1.31

Long Run Cumulative Net Savings (Cost): $292.7 million

Long Run Cumulative Net Savings (Cost) Per Student: $13,923

Long Run Savings For Each Dollar of Program Expenditure: $2.68

OPPORTUNITY SCHOLARSHIPS PROGRAM

Plan parameters described below were in effect during FY 2018, the latest year in the analysis, and may not reflect provisions currently in place.

The District of Columbia Opportunity Scholarships Program (DCOSP), authorized by the U.S. Congress in 2004, provides vouchers to low-income students to attend a private school of choice. It is the only federally funded program and is overseen by the U.S. Department of Education. To be eligible for the program, families must be current residents of D.C. and either receive benefits under the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) or earn no more than 185 percent of the federal poverty level prior to entering the program. Students may continue to receive vouchers in later years provided their household income does not rise above 300 percent of the poverty level. Students receive priority if they previously attended public schools identified as one of the lowest-performing under the District of Columbia’s accountability system or if they or their siblings already are participating in the program

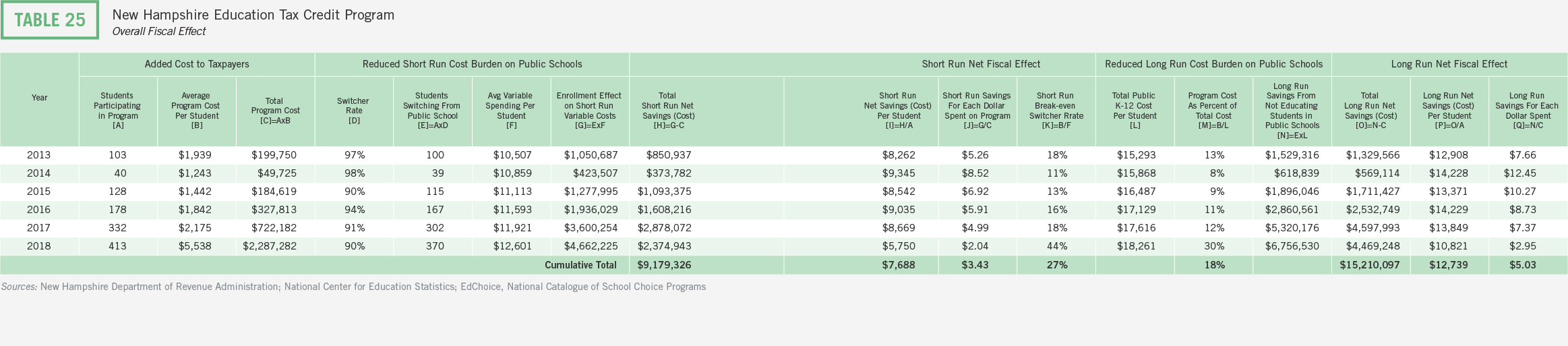

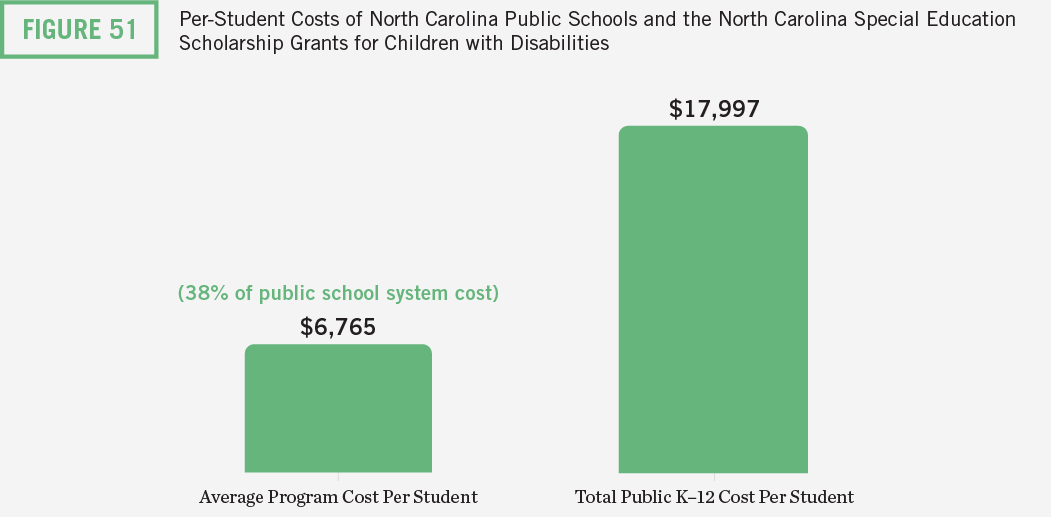

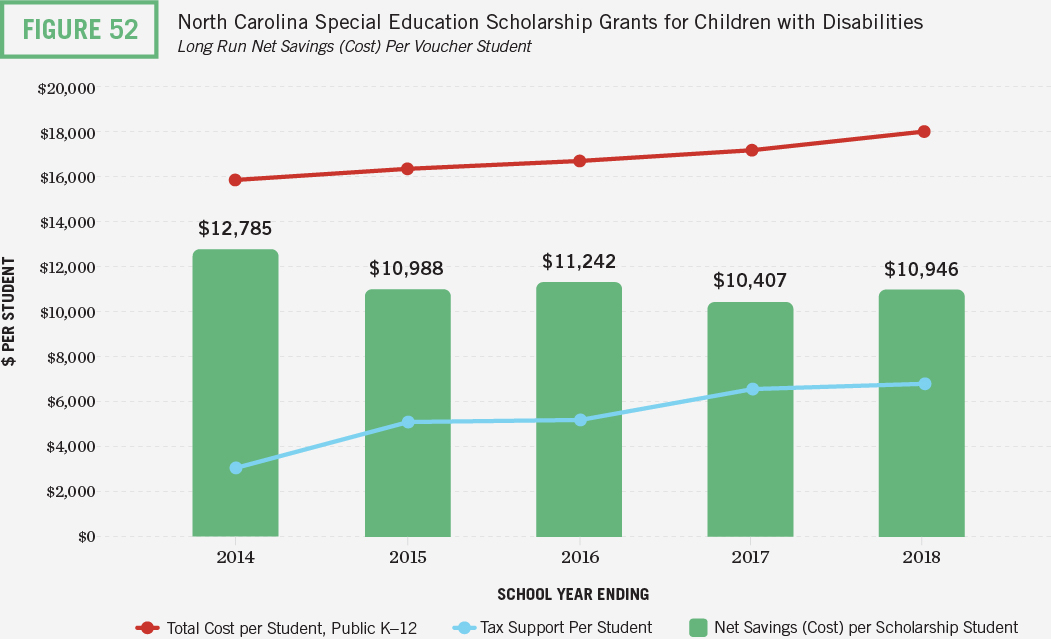

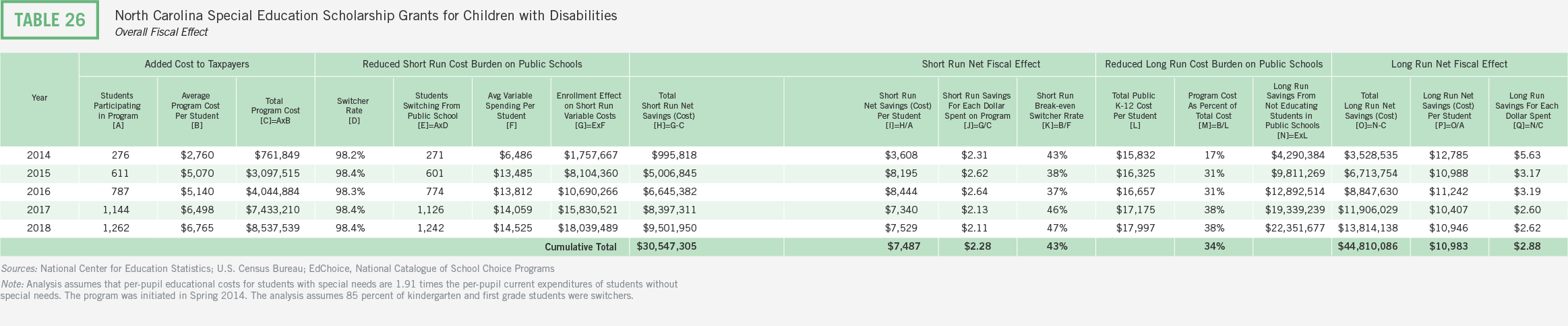

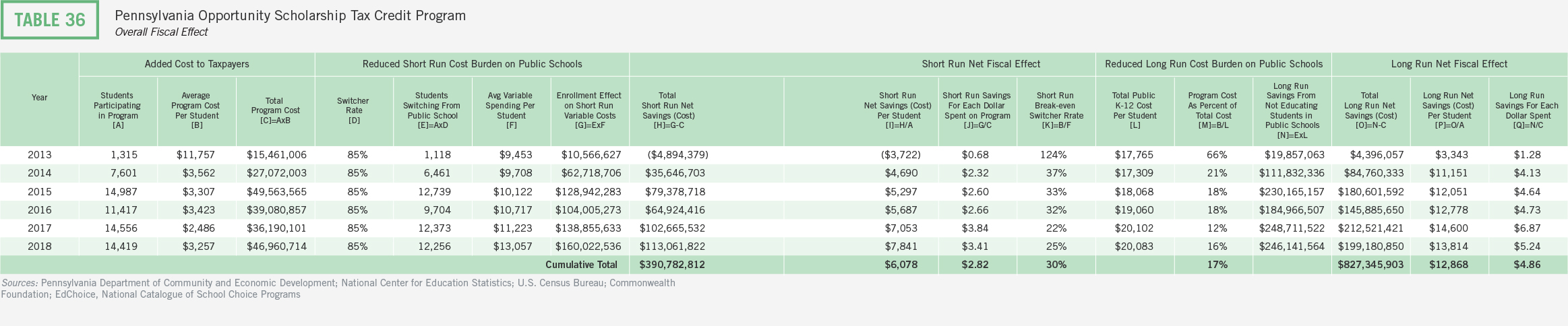

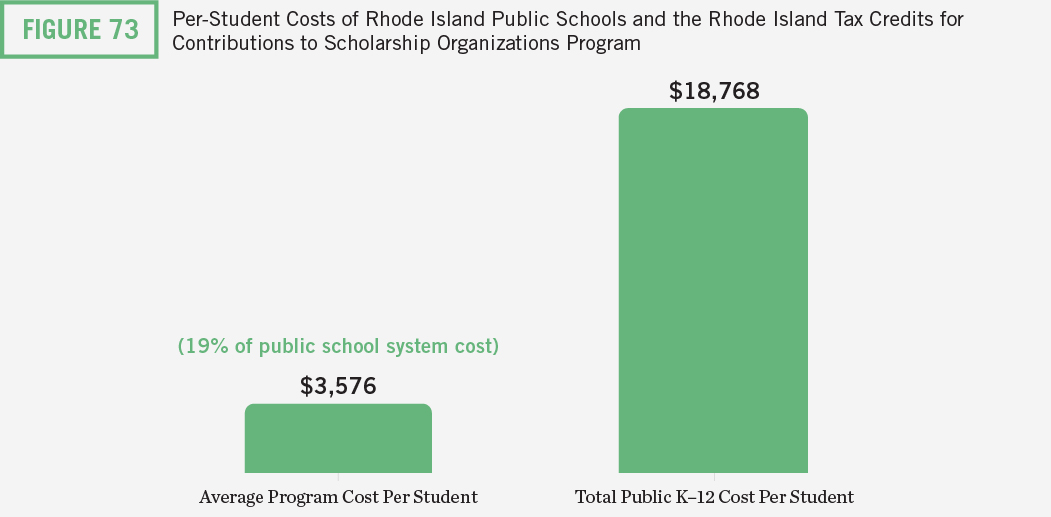

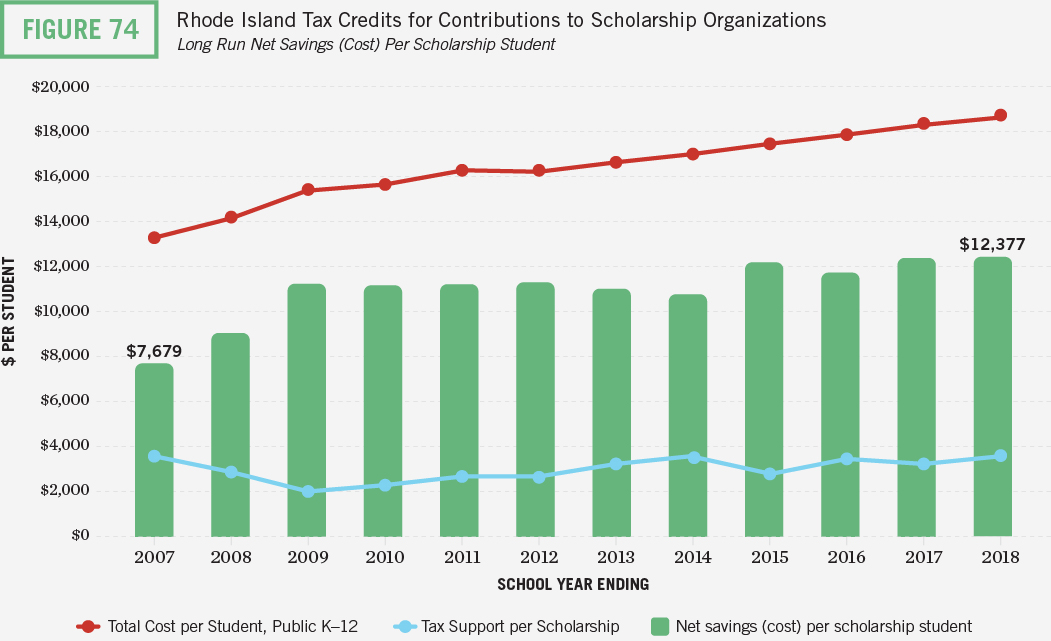

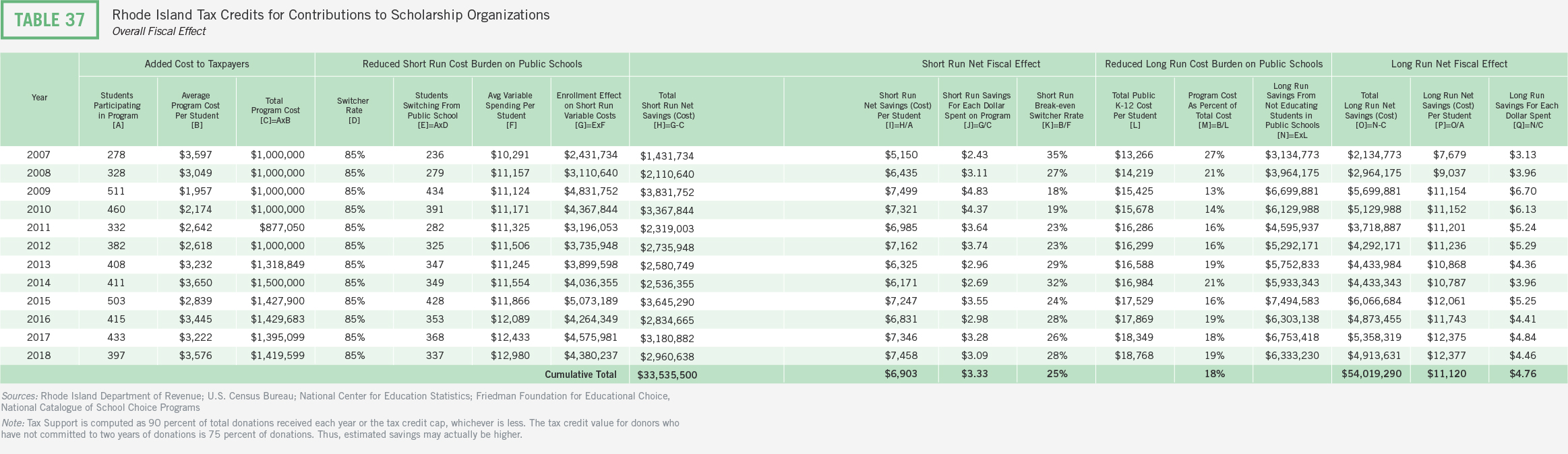

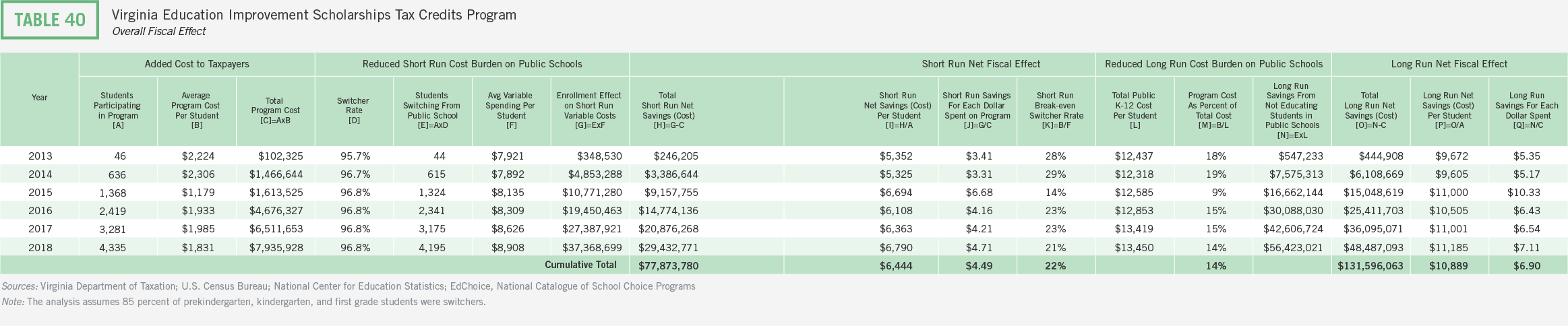

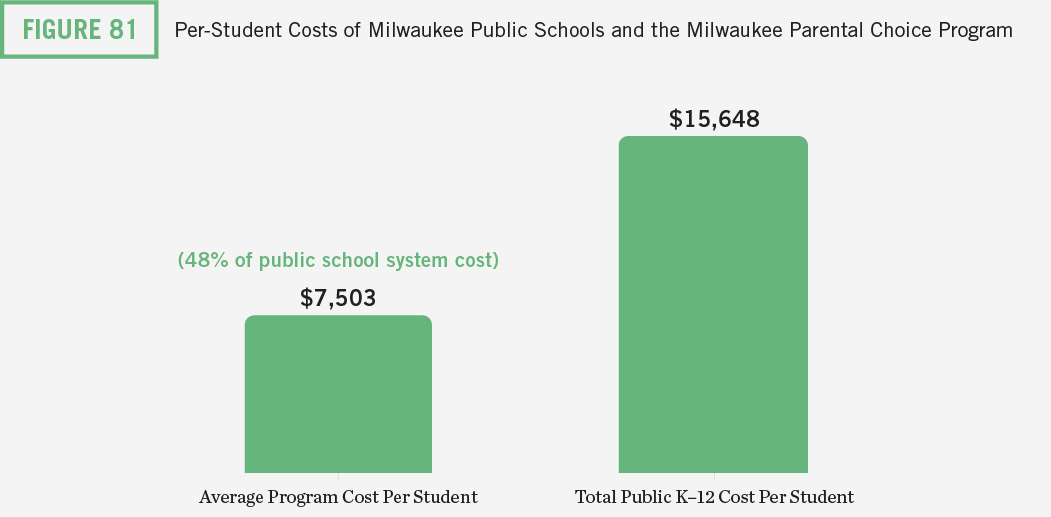

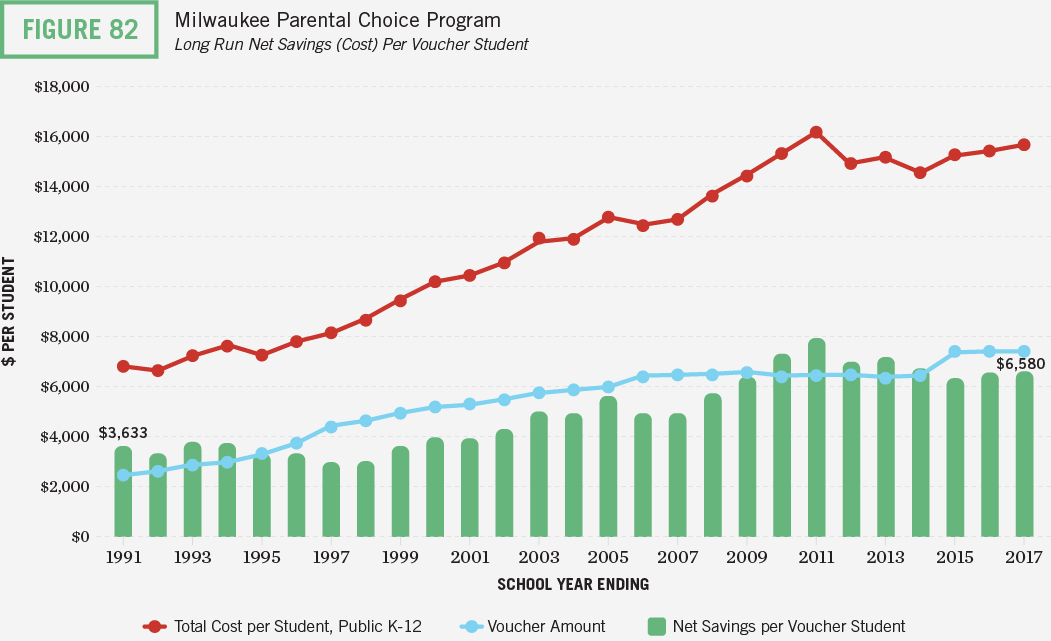

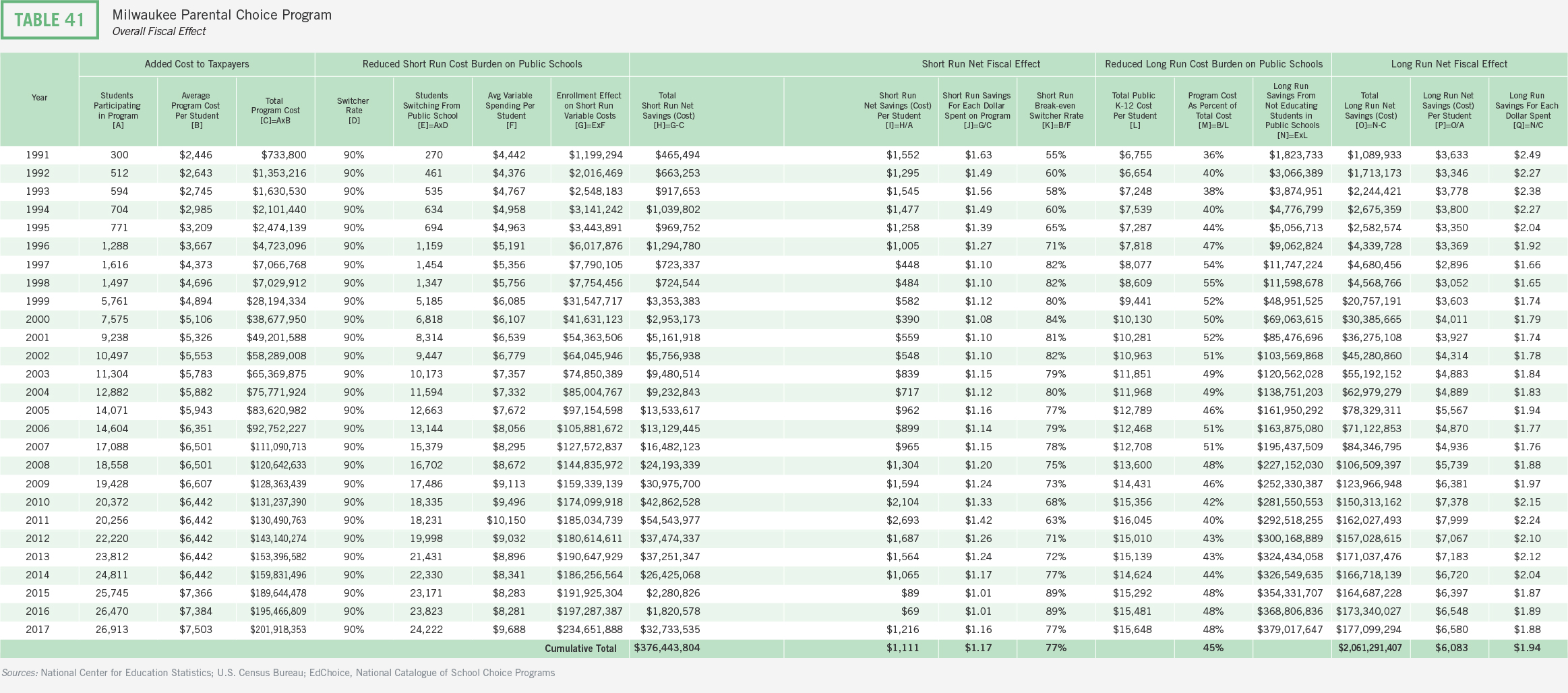

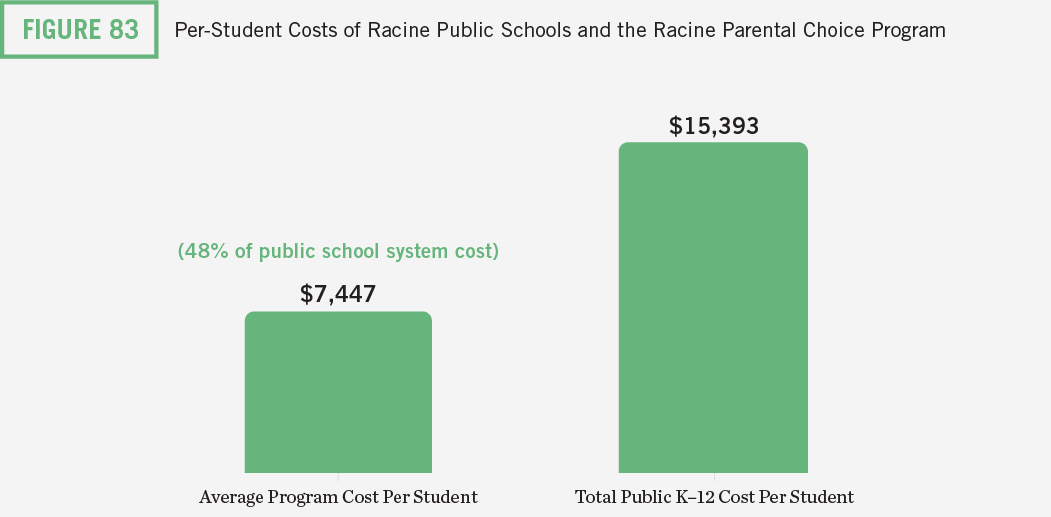

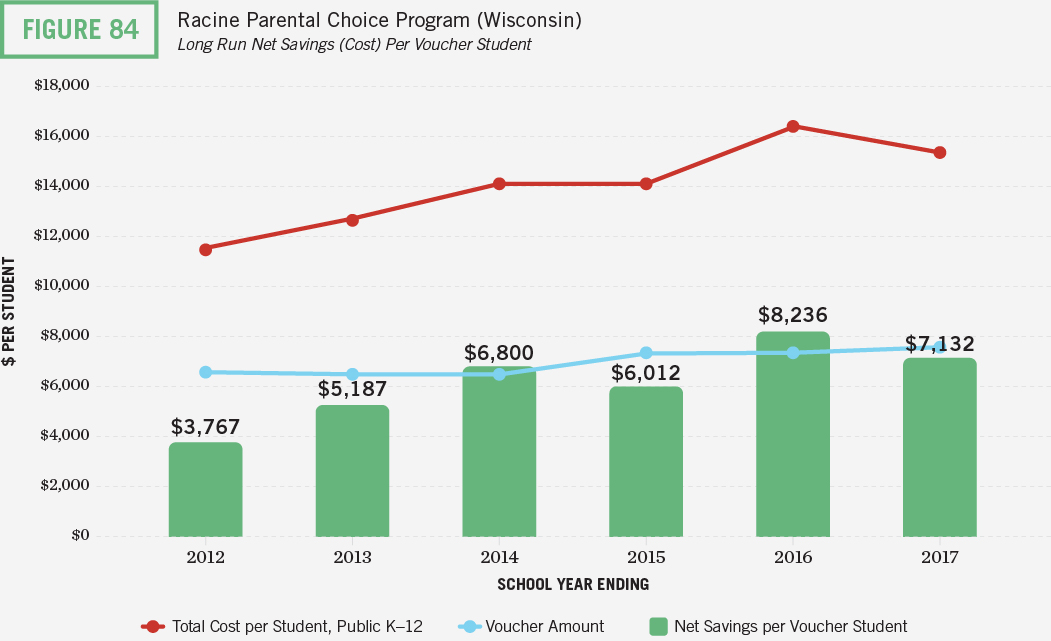

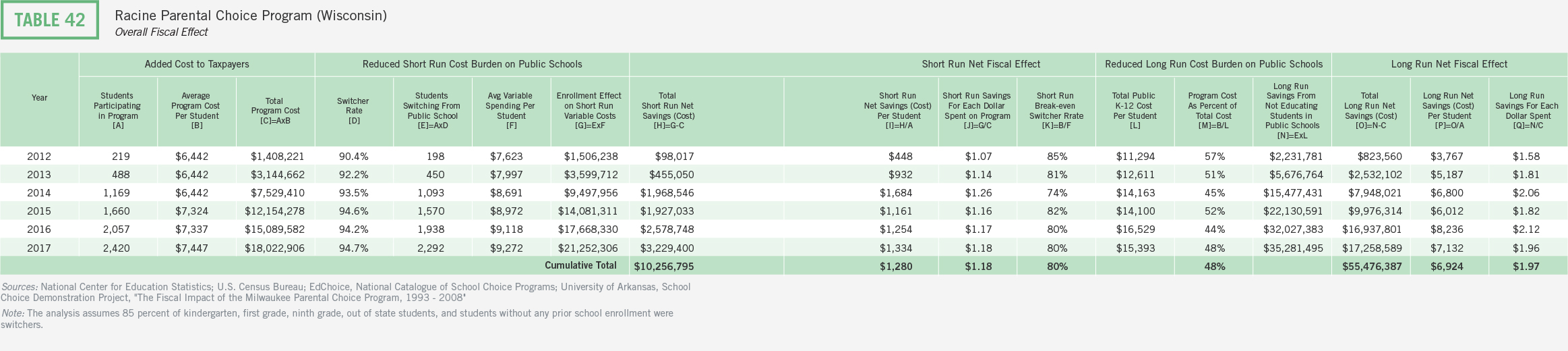

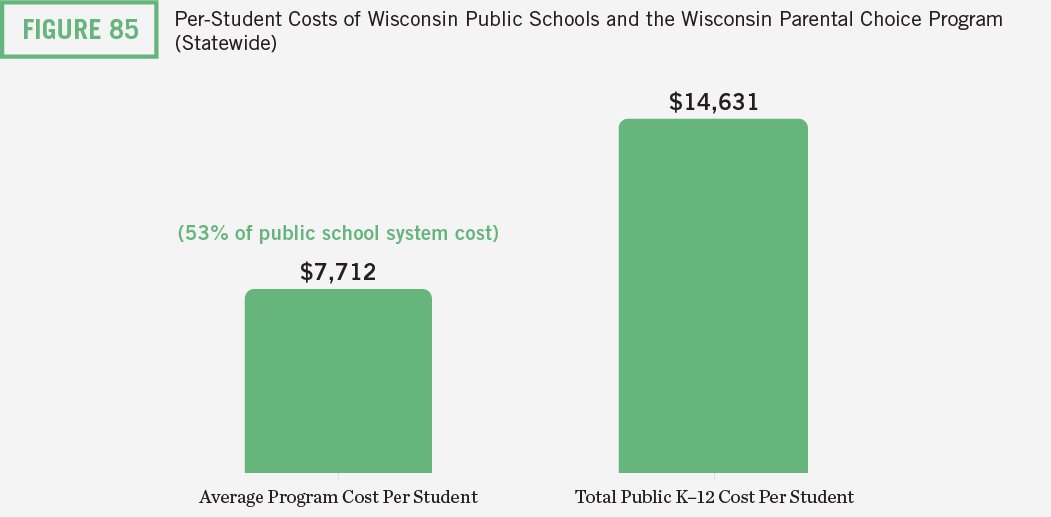

Through 2011, vouchers were fixed at $7,500 per student. Today, voucher amounts depend on grade level. In 2017–18, students in K–8 may received a voucher worth up to $8,653 while students in grades 9–12 may receive vouchers worth up to $12,981. These amounts are adjusted for inflation each year. The program is authorized at $20 million in available funding, meaning that about 2,000 students would be able to participate in the program, depending on students’ grade levels.